Sitka is a unified city-borough in the southeast portion of the U.S. state of Alaska. It was under Russian rule from 1799 to 1867. The city is situated on the west side of Baranof Island and the south half of Chichagof Island in the Alexander Archipelago of the Pacific Ocean. As of the 2020 census, Sitka had a population of 8,458, making it the fifth-most populated city in the state.

Angoon is a city on Admiralty Island in Hoonah-Angoon Census Area, Alaska, United States. At the 2000 census the population was 572; by the 2010 census the population had declined to 459. The name in Tlingit, Aangóon, means roughly "isthmus town."

The National Zoological Park, commonly known as the National Zoo, is one of the oldest zoos in the United States. The zoo is part of the Smithsonian Institution and does not charge admission. Founded in 1889, its mission is to "provide engaging experiences with animals and create and share knowledge to save wildlife and habitats".

Woodland Park Zoo is a wildlife conservation organization and zoological garden located in the Phinney Ridge neighborhood of Seattle, Washington, United States. The zoo is the recipient of over 65 awards across multiple categories. The zoo has around 900 animals from 250 species and the zoo has over 1 million visitors a year.

The Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge is a United States National Wildlife Refuge in the Kodiak Archipelago in southwestern Alaska, United States.

The Kodiak bear, also known as the Kodiak brown bear, sometimes the Alaskan brown bear, inhabits the islands of the Kodiak Archipelago in southwest Alaska. It is one of the largest recognized subspecies or population of the brown bear, and one of the two largest bears alive today, the other being the polar bear. They are also considered by some to be a population of grizzly bears.

The Alaska Zoo is a zoo in Anchorage, Alaska, located on 25 acres (10 ha) of the Anchorage Hillside. It is a popular attraction in Alaska, with nearly 200,000 visitors per year.

The McNeil River is a river on the eastern drainage of the Alaska Peninsula near its base and conjunction with the Alaska mainland. The McNeil emerges from glaciers and alpine lakes in the mountains of the Aleutian Range. The river's destination is the Cook Inlet in Alaska's southwest. The McNeil is the prime habitat of numerous animals, but it is famous for its salmon and brown bears. This wealth of wildlife was one of the reasons for the Alaska State Legislature's decision to designate the McNeil River a wildlife sanctuary in 1967. In 1993, this protected area was enlarged to preserve an area that has the highest concentration of brown bears anywhere in the world. According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, up to 144 brown bears have been sighted on the river in a single summer with 74 bears congregating in one place at a time Its entire length of 35 miles (55 km) lies within the McNeil River State Game Sanctuary, created in 1967 by the State of Alaska to protect the numerous Alaska brown bears who frequented the area. It also lies entirely within the Kenai Peninsula Borough boundaries. The McNeil River State Game Sanctuary and Refuge is part of a 3.8-million-acre (1,500,000 ha) piece of land that is protected from hunting; the rest of this is Katmai National Park.

Knut was an orphaned polar bear born in captivity at the Berlin Zoological Garden. Rejected by his mother at birth, he was raised by zookeepers. He was the first polar bear cub to survive past infancy at the Berlin Zoo in more than 30 years. At one time the subject of international controversy, he became a tourist attraction and commercial success. After the German tabloid newspaper Bild ran a quote from an animal rights activist that decried keeping the cub in captivity, fans worldwide rallied in support of his being hand-raised by humans. Children protested outside the zoo, and e-mails and letters expressing sympathy for the cub's life were sent from around the world.

Bear-baiting is a blood sport in which a chained bear and one or more dogs are forced to fight one another. It may also involve pitting a bear against another animal. Until the 19th century, it was commonly performed in Great Britain, Sweden, India, Pakistan, and Mexico among others.

River Wonders, formerly known as River Safari, is a river-themed zoo and aquarium located in Mandai, Singapore, forming part of the Mandai Wildlife Reserve. It is built over 12 hectares and nestled between its two counterparts, the Singapore Zoo and the Night Safari, Singapore. It is the first of its kind in Asia and features freshwater exhibits and a river boat ride as its main highlights. The safari was built at a cost of S$160m, with an expected visitor rate of 820,000 people yearly.

Baranof Island is an island in the northern Alexander Archipelago in the Alaska Panhandle, in Alaska. The name "Baranof" was given to the island in 1805 by Imperial Russian Navy captain U. F. Lisianski in honor of Alexander Andreyevich Baranov. It was called Sheet’-ká X'áat'l by the native Tlingit people. It is the smallest of the ABC islands of Alaska. The indigenous group native to the island, the Tlingit, named the island Shee Atika. Baranof island is home to a diverse ecosystem, which made it a prime location for the fur trading company, the Russian American Company. Russian occupation in Baranof Island impacted not only the indigenous population as well as the ecology of the island, but also led to the United States' current ownership over the land.

The grizzly bear, also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

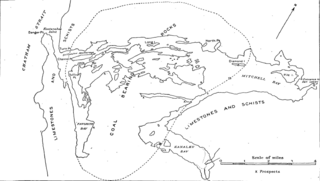

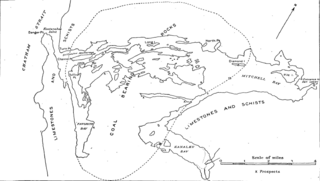

Kootznahoo Inlet is located on the eastern shore of Chatham Strait in the U.S. state of Alaska. Comprising an area of about 15 square miles (39 km2), it is an intricate group of narrow passages, lagoons, and bays, having its entrance 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Killisnoo. Kootznahoo, which means bear fortress, is also the name given by the Tlingit to mean Admiralty. The Kootznoowoo Wilderness also of the Admiralty Island covers some of the largest reserve areas covering about 1 million acres. The island is inhabited by about 1500 brown bears, the largest number recorded anywhere on the earth.

The Sitka Pulp Mill was a pulp mill located on the North and West Shores of Sawmill Cove, approximately five miles East of Sitka, Alaska. In 1956, the mill site was purchased from Freda and John Van Horn by the Alaska Pulp Corporation. This was the first Japanese investment in the United States of America since World War II, and the mill operated from 1959 until 1993. The majority of production was used to create rayon fabric, and to supply Japan with logs to rebuild homes and infrastructure after World War II. In the later years of the mill, as the demand for rayon and logs for rebuilding decreased, the primary focus of the mill became the manufacture of paper.

The Smokey Bear Show is an American-Japanese animated television series that aired on ABC's Saturday morning schedule, produced by Rankin/Bass Productions. The show features Smokey Bear, the icon of the United States Forest Service, who was well known for his 1947 slogan, "Remember... only YOU can prevent forest fires". It aired for one season of 17 episodes starting on September 6, 1969, and then aired in reruns for the 1970–1971 season. When the show was lacking in competition with Bugs Bunny and other renowned cartoons at the time, it was cancelled. The show is largely lost, as only 4 of the 17 episodes have been recovered as of October 15, 2023.

Hank the Tank is a five-hundred pound female American black bear that lived in Tahoe Keys, California before being captured and relocated to Colorado. Hank, known to wildlife officials as Bear 64F, became notable for press coverage of her "ransacking" the Lake Tahoe community, breaking into houses in search of food and causing property damage. Overall, she broke into over 20 homes. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) said that Hank had lost her fear of people, and it was thought that the year-round availability of food meant that Hank had not been hibernating, as is also the case for around twenty percent of the bears in the area.