Eridu was a Sumerian city located at Tell Abu Shahrain, also Abu Shahrein or Tell Abu Shahrayn, an archaeological site in Lower Mesopotamia. It is located in Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq, near the modern city of Basra. Eridu is traditionally considered the earliest city in southern Mesopotamia based on the Sumerian King List. Located 12 kilometers southwest of the ancient site of Ur, Eridu was the southernmost of a conglomeration of Sumerian cities that grew around temples, almost in sight of one another. The city gods of Eridu were Enki and his consort Damkina. Enki, later known as Ea, was considered to have founded the city. His temple was called E-Abzu, as Enki was believed to live in Abzu, an aquifer from which all life was thought to stem. According to Sumerian temple hymns, another name for the temple of Ea/Enki was called Esira (Esirra).

"... The temple is constructed with gold and lapis lazuli, Its foundation on the nether-sea (apsu) is filled in. By the river of Sippar (Euphrates) it stands. O Apsu pure place of propriety, Esira, may thy king stand within thee. ..."

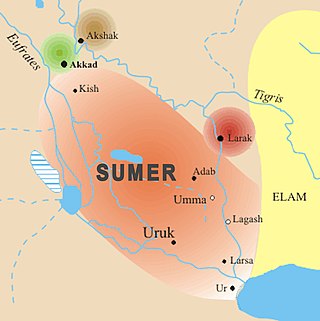

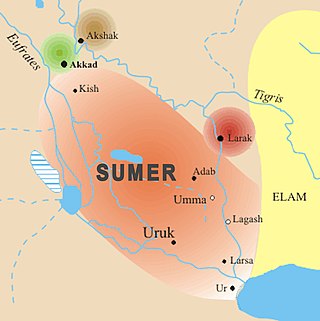

Sumer is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia, emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. Like nearby Elam, it is one of the cradles of civilization, along with Egypt, the Indus Valley, the Erligang culture of the Yellow River valley, Caral-Supe, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture of the Carpathian Mountains, and Mesoamerica. Living along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, a surplus which enabled them to form urban settlements. The world's earliest known texts come from the Sumerian cities of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr, and date to between c. 3350 – c. 2500 BC, following a period of proto-writing c. 4000 – c. 2500 BC.

The Sumerian King List or Chronicle of the One Monarchy is an ancient literary composition written in Sumerian that was likely created and redacted to legitimize the claims to power of various city-states and kingdoms in southern Mesopotamia during the late third and early second millennium BC. It does so by repetitively listing Sumerian cities, the kings that ruled there, and the lengths of their reigns. Especially in the early part of the list, these reigns often span thousands of years. In the oldest known version, dated to the Ur III period but probably based on Akkadian source material, the SKL reflected a more linear transition of power from Kish, the first city to receive kingship, to Akkad. In later versions from the Old Babylonian period, the list consisted of a large number of cities between which kingship was transferred, reflecting a more cyclical view of how kingship came to a city, only to be inevitably replaced by the next. In its best-known and best-preserved version, as recorded on the Weld-Blundell Prism, the SKL begins with a number of antediluvian kings, who ruled before a flood swept over the land, after which kingship went to Kish. It ends with a dynasty from Isin, which is well-known from other contemporary sources.

The history of Sumer spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE in southern Mesopotamia, and is taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumer was the region's earliest known civilization and ended with the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE. It was followed by a transitional period of Amorite states before the rise of Babylonia in the 18th century BCE.

Nippur was an ancient Sumerian city. It was the special seat of the worship of the Sumerian god Enlil, the "Lord Wind", ruler of the cosmos, subject to An alone. Nippur was located in modern Nuffar 5 miles north of modern Afak, Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq. It is roughly 200 kilometers south of modern Baghdad and about 96.54 km southeast of the ancient city of Babylon. Occupation at the site extended back to the Ubaid period, the Uruk period, and the Jemdet Nasr period. The origin of the ancient name is unknown but different proposals have been made.

Umma (Sumerian: 𒄑𒆵𒆠ummaKI; in modern Dhi Qar Province in Iraq, was an ancient city in Sumer. There is some scholarly debate about the Sumerian and Akkadian names for this site. Traditionally, Umma was identified with Tell Jokha. More recently it has been suggested that it was located at Umm al-Aqarib, less than 7 km to its northwest or was even the name of both cities. One or both were the leading city of the Early Dynastic kingdom of Gišša, with the most recent excavators putting forth that Umm al-Aqarib was prominent in EDIII but Jokha rose to preeminence later. The town of KI.AN was also nearby. KI.AN, which was destroyed by Rimush, a ruler of the Akkadian Empire. There are known to have been six gods of KI.AN including Gula KI.AN and Sara KI.AN.

Isin (Sumerian: 𒉌𒋛𒅔𒆠, romanized: I3-si-inki, modern Arabic: Ishan al-Bahriyat) is an archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq which was the location of the Ancient Near East city of Isin, occupied from the late 4th millennium Uruk period up until at least the late 1st millennium BC Neo-Babylonian period. It lies about 40 km (25 mi) southeast of the modern city of Al Diwaniyah.

Adab was an ancient Sumerian city between Girsu and Nippur, lying about 35 kilometers southeast of the latter. It was located at the site of modern Bismaya or Bismya in the Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate of Iraq. The site was occupied at least as early as the 3rd Millenium BC, through the Early Dynastic, Akkadian Empire, and Ur III empire periods, into the Kassite period in the mid-2nd millennium BC. It is known that there were temples of Ninhursag/Digirmah, Iskur, Asgi, Inanna and Enki at Adab and that the city-god of Adab was Parag'ellilegarra (Panigingarra) "The Sovereign Appointed by Ellil".

Ur-Nammu founded the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, in southern Mesopotamia, following several centuries of Akkadian and Gutian rule. Though he built many temples and canals his main achievement was building the core of the Ur III Empire via military conquest, and Ur-Nammu is chiefly remembered today for his legal code, the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known surviving example in the world. He held the titles of "King of Ur, and King of Sumer and Akkad". His personal goddess was Ninsuna.

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider to have been a nascent empire.

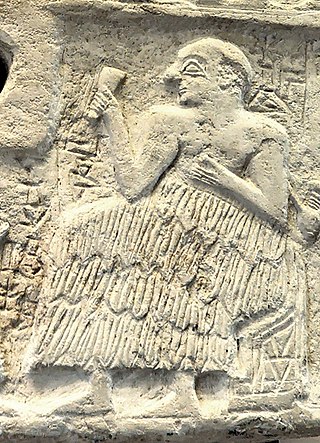

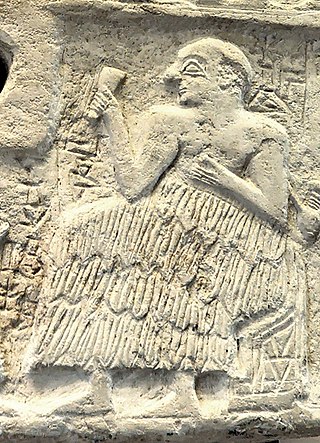

Ur-Nanshe also Ur-Nina, was the first king of the First Dynasty of Lagash in the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period III. He is known through inscriptions to have commissioned many building projects, including canals and temples, in the state of Lagash, and defending Lagash from its rival state Umma. He was probably not from royal lineage, being the son of Gunidu who was recorded without an accompanying royal title. He was the father of Akurgal, who succeeded him, and grandfather of Eannatum. Eannatum expanded the kingdom of Lagash by defeating Umma as illustrated in the Stele of the Vultures and continued the building and renovation of Ur-Nanshe's original buildings.

Shulgi of Ur was the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years, from c. 2094 – c. 2046 BC. His accomplishments include the completion of construction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, begun by his father Ur-Nammu. On his inscriptions, he took the titles "King of Ur", "King of Sumer and Akkad", adding "King of the four corners of the universe" in the second half of his reign. He used the symbol for divinity before his name, marking his apotheosis, from at least the 21rd year of his reign and was worshipped in the Ekhursag palace he built. Shulgi was the son of Ur-Nammu king of Ur and his queen consort Watartum.

Entemena, also called Enmetena, lived circa 2400 BC, was a son of Enannatum I who he re-established Lagash as a power in Sumer. He defeated Il, king of Umma, in a territorial conflict through an alliance with Lugal-kinishe-dudu of Uruk, successor to Enshakushanna, who is in the king list. The tutelary deity Shul-utula was his personal deity. His reign lasted at least 19 years.

Gatumdug was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the tutelary deity of Lagash and closely associated with its kings. She was initially worshiped only in this city and in NINA, but during the reign of Gudea a temple was built for her in Girsu. She appears in a number of literary compositions, including the hymn inscribed on the Gudea cylinders and Lament for Sumer and Ur.

The E-ninnu 𒂍𒐐 was the E (temple) to the warrior god Ningirsu in the Sumerian city of Girsu in southern Mesopotamia. Girsu was the religious centre of a state that was named Lagash after its most populous city, which lay 25 km southeast of Girsu. Rulers of Lagash who contributed to the structure of the E-ninnu included Ur-Nanshe of Lagash in the late 26th century BC, his grandson Eannatum in the following century, Urukagina in the 24th century and Gudea, ruler of Lagash in the mid 22nd century BC.

Self-praise of Shulgi is a Sumerian hymn dedicated to the Third Dynasty of Ur ruler Shulgi, written on clay tablets dated to between 2100 and 2000 BC.

Ekur, also known as Duranki, is a Sumerian term meaning "mountain house". It is the assembly of the gods in the Garden of the gods, parallel in Greek mythology to Mount Olympus and was the most revered and sacred building of ancient Sumer.

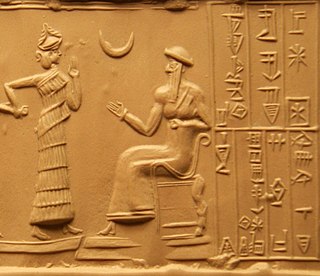

Iddin-Dagan, fl.c. 1910 BC — c. 1890 BC by the short chronology or c. 1975 BC — c. 1954 BC by the middle chronology) was the 3rd king of the dynasty of Isin. Iddin-Dagan was preceded by his father Shu-Ilishu. Išme-Dagān then succeeded Iddin-Dagan. Iddin-Dagan reigned for 21 years He is best known for his participation in the sacred marriage rite and the sexually-explicit hymn that described it.

Nimintabba was a Goddess of Sumer. She is thought to have been a local deity of the city of Ur, as her only known temple was located there. Her worship was particularly associated with king Shulgi, and there are no previous attestations of her.

Puzrish-Dagan is an important archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate (Iraq). It is best-known for the thousands of clay tablets that are known to have come from the site through looting during the early twentieth century.