In phonology, an allophone is one of multiple possible spoken sounds – or phones – used to pronounce a single phoneme in a particular language. For example, in English, the voiceless plosive and the aspirated form are allophones for the phoneme, while these two are considered to be different phonemes in some languages such as Central Thai. Similarly, in Spanish, and are allophones for the phoneme, while these two are considered to be different phonemes in English.

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract, except for the h sound, which is pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Examples are and [b], pronounced with the lips; and [d], pronounced with the front of the tongue; and [g], pronounced with the back of the tongue;, pronounced throughout the vocal tract;, [v], and, pronounced by forcing air through a narrow channel (fricatives); and and, which have air flowing through the nose (nasals). Most consonants are pulmonic, using air pressure from the lungs to generate a sound. Very few natural languages are non-pulmonic, making use of ejectives, implosives, and clicks. Contrasting with consonants are vowels.

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is an alphabetic system of phonetic notation based primarily on the Latin script. It was devised by the International Phonetic Association in the late 19th century as a standard written representation for the sounds of speech. The IPA is used by lexicographers, foreign language students and teachers, linguists, speech–language pathologists, singers, actors, constructed language creators, and translators.

In phonology, minimal pairs are pairs of words or phrases in a particular language, spoken or signed, that differ in only one phonological element, such as a phoneme, toneme or chroneme, and have distinct meanings. They are used to demonstrate that two phones represent two separate phonemes in the language.

Morphophonology is the branch of linguistics that studies the interaction between morphological and phonological or phonetic processes. Its chief focus is the sound changes that take place in morphemes when they combine to form words.

A phoneme is any set of similar speech sounds that is perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word from another. All languages contain phonemes, and all spoken languages include both consonant and vowel phonemes. Phonemes are primarily studied under the branch of linguistics known as phonology.

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages systematically organize their Phonemes or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a particular language variety. At one time, the study of phonology related only to the study of the systems of phonemes in spoken languages, but now it may relate to any linguistic analysis either:

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (length). They are usually voiced and are closely involved in prosodic variation such as tone, intonation and stress.

A syllable is a basic unit of organization within a sequence of speech sounds, such as within a word, typically defined by linguists as a nucleus with optional sounds before or after that nucleus. In phonology and studies of languages, syllables are often considered the "building blocks" of words. They can influence the rhythm of a language, its prosody, its poetic metre and its stress patterns. Speech can usually be divided up into a whole number of syllables: for example, the word ignite is made of two syllables: ig and nite.

In phonetics and phonology, a semivowel, glide or semiconsonant is a sound that is phonetically similar to a vowel sound but functions as the syllable boundary, rather than as the nucleus of a syllable. Examples of semivowels in English are y and w in yes and west, respectively. Written in IPA, y and w are near to the vowels ee and oo in seen and moon, written in IPA. The term glide may alternatively refer to any type of transitional sound, not necessarily a semivowel.

In phonetics, palatalization or palatization is a way of pronouncing a consonant in which part of the tongue is moved close to the hard palate. Consonants pronounced this way are said to be palatalized and are transcribed in the International Phonetic Alphabet by affixing the letter ⟨ʲ⟩ to the base consonant. Palatalization is not phonemic in English, but it is in Slavic languages such as Russian and Ukrainian, Finnic languages such as Estonian and Võro, Irish, Marshallese, Kashmiri, and Japanese.

Historical Chinese phonology deals with reconstructing the sounds of Chinese from the past. As Chinese is written with logographic characters, not alphabetic or syllabary, the methods employed in Historical Chinese phonology differ considerably from those employed in, for example, Indo-European linguistics; reconstruction is more difficult because, unlike Indo-European languages, no phonetic spellings were used.

The phonology of Vietnamese features 19 consonant phonemes, with 5 additional consonant phonemes used in Vietnamese's Southern dialect, and 4 exclusive to the Northern dialect. Vietnamese also has 14 vowel nuclei, and 6 tones that are integral to the interpretation of the language. Older interpretations of Vietnamese tones differentiated between "sharp" and "heavy" entering and departing tones. This article is a technical description of the sound system of the Vietnamese language, including phonetics and phonology. Two main varieties of Vietnamese, Hanoi and Saigon, which are slightly different to each other, are described below.

In linguistics, a chroneme is an abstract phonological suprasegmental feature used to signify contrastive differences in the length of speech sounds. Both consonants and vowels can be viewed as displaying this features. The noun chroneme is derived from Ancient Greek χρόνος (khrónos) 'time', and the suffixed -eme, which is analogous to the -eme in phoneme or morpheme. Two words with different meaning that are spoken exactly the same except for length of one segment are considered a minimal pair. The term was coined by the British phonetician Daniel Jones to avoid using the term phoneme to characterize a feature above the segmental level.

This article describes the phonology of the Somali language.

Proto-Polynesian is the hypothetical proto-language from which all the modern Polynesian languages descend. It is a daughter language of the Proto-Austronesian language. Historical linguists have reconstructed the language using the comparative method, in much the same manner as with Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Uralic. This same method has also been used to support the archaeological and ethnographic evidence which indicates that the ancestral homeland of the people who spoke Proto-Polynesian was in the vicinity of Tonga, Samoa, and nearby islands.

A diaphoneme is an abstract phonological unit that identifies a correspondence between related sounds of two or more varieties of a language or language cluster. For example, some English varieties contrast the vowel of late with that of wait or eight. Other English varieties contrast the vowel of late or wait with that of eight. This non-overlapping pair of phonemes from two different varieties can be reconciled by positing three different diaphonemes: A first diaphoneme for words like late, a second diaphoneme for words like wait, and a third diaphoneme for words like eight.

The phonology of Bengali, like that of its neighbouring Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, is characterised by a wide variety of diphthongs and inherent back vowels.

Standard Cantonese pronunciation originates from Guangzhou, also known as Canton, the capital of Guangdong Province. Hong Kong Cantonese is closely related to the Guangzhou dialect, with only minor differences. Yue dialects spoken in other parts of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces, such as Taishanese, exhibit more significant divergences.

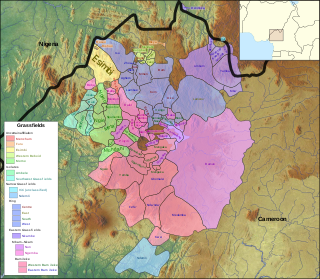

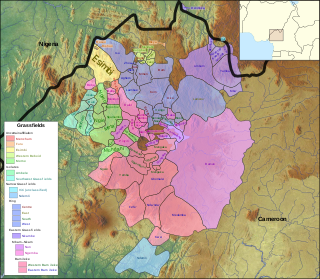

Babanki, or Kejom, is a Bantoid language that is spoken by the Babanki people of the Western Highlands of Cameroon.