Washington Square is a park in downtown Charleston, South Carolina. It is located behind City Hall at the corner of Meeting Street and Broad Street in the Charleston Historic District. The planting beds and red brick walks were installed in April 1881. It was known as City Hall Park until October 19, 1881, when it was renamed in honor of George Washington. The new name was painted over the gates in December 1881.

Marion Square is greenspace in downtown Charleston, South Carolina, spanning six and one half acres. The square was established as a parade ground for the state arsenal under construction on the north side of the square. It is best known as the former Citadel Green because The Citadel occupied the arsenal from 1843 until 1922, when the Citadel moved to the city's west side. Marion Square was named in honor of Francis Marion.

Bishop England High School is a diocesan Roman Catholic four-year high school in Charleston, South Carolina, United States. It was located on Calhoun Street in downtown Charleston until it moved to a newly constructed 40-acre campus located on Daniel Island in 1998. With an enrollment of 730, Bishop England is the largest private high school in the state of South Carolina. The school was founded in 1915 and was named after John England, the first bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston.

The Charleston Symphony Orchestra aka CSO, is an American orchestra based in Charleston, South Carolina and performs Masterworks and Pops series, Youth Orchestra concerts and more, at the Gaillard Center and dozens of other venues across the Lowcountry. The current roster of full-time, salaried core musicians is 24. The orchestra supplements its core by bringing more than 400 professionally auditioned guest musicians to Charleston annually.

The City Market is a historic market complex in downtown Charleston, South Carolina. Established in the 1790s, the market stretches for four city blocks from the architecturally-significant Market Hall, which faces Meeting Street, through a continuous series of one-story market sheds, the last of which terminates at East Bay Street. The market should not be confused with the Old Slave Mart where enslaved people were sold, as enslaved people were never sold in the City Market. The City Market Hall has been described as a building of the "highest architectural design quality." The entire complex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as Market Hall and Sheds and was further designated a National Historic Landmark.

The William Enston Home, located at 900 King St., Charleston, South Carolina, is a complex of many buildings all constructed in Romanesque Revival architecture, a rare style in Charleston. Twenty-four cottages were constructed beginning in 1887 along with a memorial chapel at the center with a campanile style tower, and it was reserved for white residents. An infirmary was added in 1931 and later converted into a superintendent's home.

David Burns Hyer was an American architect who practiced in Charleston, South Carolina and Orlando, Florida during the first half of the twentieth century, designing civic buildings in the Neoclassical Revival and Mediterranean Revival styles.

Edward Culliatt Jones was an American architect from Charleston, South Carolina. A number of his works are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, and two are further designated as U.S. National Historic Landmarks. His works include the following :

Cannon Park is a 2.7 acre public park located in peninsular Charleston, South Carolina. It is bound to the north by Calhoun St. and to the south by Bennett St. To the east and west are Rutledge Ave. and Ashley Ave. respectively.

Corrine Jones Playground was formerly known as Hester Park because of its location along Hester Street in Charleston, South Carolina. The playground is located on a portion of the larger Buist Tract that had been used during World War II as housing for the influx of wartime workers.

Augustus E. Constantine was an architect in Charleston, South Carolina. He is known for his Art Moderne architecture.

The Williams Mansion is a Victorian house at 16 Meeting St., Charleston, South Carolina. The mansion is open for public tours.

John Palmer Gaillard Jr. was an American politician who was mayor of Charleston, South Carolina from 1959 to 1975. The Gaillard Center is named after him. During his tenure, Gaillard significantly expanded the size of Charleston by annexing nearby neighborhoods.

Arthur Bonnell Schirmer Jr. was the fifty-ninth mayor of Charleston, South Carolina, completing the final four months of J. Palmer Gaillard, after Gaillard's resignation. He did not run for election for a full term.

The Faber House is a historic building in Hampstead Village in Charleston, South Carolina that was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2019.

The Charleston sanitation strike was a more than two-month movement in Charleston, South Carolina that protested the pay and working conditions of Charleston's overwhelmingly African-American sanitation workers.

Memminger Auditorium is a live performance and special events venue in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Florence Crittenton Home is an institution for the support of unwed mothers at 19 St. Margaret St. in Charleston, South Carolina that is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Gadsden Green Homes is a housing complex located in the Westside neighborhood in Charleston, South Carolina. The name comes from the neighborhood which had been owned by Christopher Gadsden. The housing project was built in two stages: the eastern half was constructed in 1942 while the western half was finished in 1968.

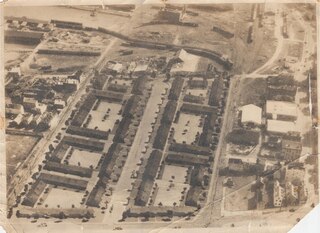

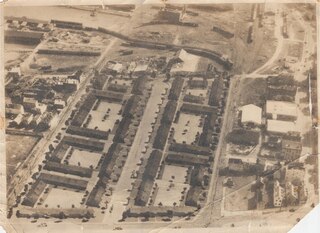

Anson Borough Homes was a housing complex located in Charleston, South Carolina bounded by Washington, Concord, Calhoun, and Laurens Streets. The project was one of a series of federally funded housing projects built in the 1930s and early 1940s during the Segregation Era. It meant to be used as housing for Black residents and would cost $2.30 per room per month.