Related Research Articles

Marcus Junius Brutus was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, which was retained as his legal name. He is often referred to simply as Brutus.

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The constitution of the Roman republic had many veto points. In order to bypass constitutional obstacles and force through the political goals of the three men, they forged in secret an alliance where they promised to use their respective influence to support each other. The "triumvirate" was not a formal magistracy, nor did it achieve a lasting domination over state affairs.

Gaius Cassius Longinus was a Roman senator and general best known as a leading instigator of the plot to assassinate Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC. He was the brother-in-law of Brutus, another leader of the conspiracy. He commanded troops with Brutus during the Battle of Philippi against the combined forces of Mark Antony and Octavian, Caesar's former supporters, and committed suicide after being defeated by Mark Antony.

Publius Clodius Pulcher was a populist Roman politician and street agitator during the time of the First Triumvirate. One of the most colourful personalities of his era, Clodius was descended from the aristocratic Claudia gens, one of Rome's oldest and noblest patrician families, but he contrived to be adopted by an obscure plebeian, so that he could be elected tribune of the plebs. During his term of office, he pushed through an ambitious legislative program, including a grain dole; but he is chiefly remembered for his long-running feuds with political opponents, particularly Cicero, whose writings offer antagonistic, detailed accounts and allegations concerning Clodius' political activities and scandalous lifestyle. Clodius was tried for the capital offence of sacrilege, following his intrusion on the women-only rites of the goddess Bona Dea, purportedly with the intention of seducing Caesar's wife Pompeia; his feud with Cicero led to Cicero's temporary exile; his feud with Milo ended in his own death at the hands of Milo's bodyguards.

The gens Claudia, sometimes written Clodia, was one of the most prominent patrician houses at ancient Rome. The gens traced its origin to the earliest days of the Roman Republic. The first of the Claudii to obtain the consulship was Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis, in 495 BC, and from that time its members frequently held the highest offices of the state, both under the Republic and in imperial times.

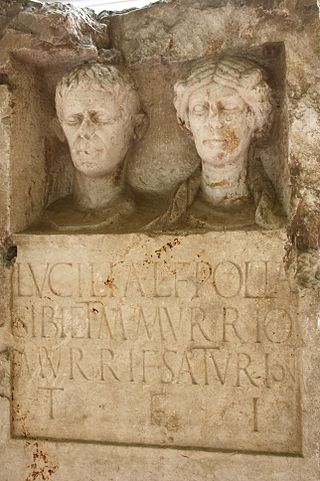

The gens Lucilia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. The most famous member of this gens was the poet Gaius Lucilius, who flourished during the latter part of the second century BC. Although many Lucilii appear in Roman history, the only one known to have obtained any of the higher offices of the Roman state was Lucilius Longus, consul suffectus in AD 7.

The Battle of Carrhae was fought in 53 BC between the Roman Republic and the Parthian Empire near the ancient town of Carrhae. An invading force of seven legions of Roman heavy infantry under Marcus Licinius Crassus was lured into the desert and decisively defeated by a mixed cavalry army of heavy cataphracts and light horse archers led by the Parthian general Surena. On such flat terrain, the Legion proved to have no viable tactics against the highly-mobile Parthian horsemen, and the slow and vulnerable Roman formations were surrounded, exhausted by constant attacks, and eventually crushed. Crassus was killed along with the majority of his army. It is commonly seen as one of the earliest and most important battles between the Roman and Parthian Empires and one of the most crushing defeats in Roman history. According to the poet Ovid in Book 6 of his poem Fasti, the battle occurred on the 9th day of June.

Appius Claudius Pulcher was a Roman patrician, politician and general in the first century BC. He was consul of the Roman Republic in 54 BC. He was an expert in Roman law and antiquities, especially the esoteric lore of the augural college of which he was a controversial member. He was head of the senior line of the most powerful family of the patrician Claudii. The Claudii were one of the five leading families which had dominated Roman social and political life from the earliest years of the republic. He is best known as the recipient of 13 of the extant letters in Cicero's ad Familiares corpus, which date from winter 53–52 to summer 50 BC. Regrettably they do not include any of Appius' replies to Cicero as extant texts of any sort by members of Rome's ruling aristocracy are quite rare, apart from those of Julius Caesar. He is also well known for being the older brother of the infamous Clodius and Clodia.

The gens Pompeia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome, first appearing in history during the second century BC, and frequently occupying the highest offices of the Roman state from then until imperial times. The first of the Pompeii to obtain the consulship was Quintus Pompeius in 141 BC, but by far the most illustrious of the gens was Gnaeus Pompeius, surnamed Magnus, a distinguished general under the dictator Sulla, who became a member of the First Triumvirate, together with Caesar and Crassus. After the death of Crassus, the rivalry between Caesar and Pompeius led to the Civil War, one of the defining events of the final years of the Roman Republic.

Theophanes of Mytilene was an intellectual and historian from the town of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos who lived in the middle of the 1st century BC. He was a friend of Pompey and wrote an adulatory history of the latter's expedition to Asia. According to Plutarch Pompey granted privileges to Mytilene for Theophanes' sake. The people of Mytilene commemorated him as a hero after his death.

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio, often referred to as Metellus Scipio, was a Roman senator and military commander. During the civil war between Julius Caesar and the senatorial faction led by Pompey, he was a staunch supporter of the latter. He led troops against Caesar's forces, mainly in the battles of Pharsalus and Thapsus, where he was defeated. He later committed suicide. Ronald Syme called him "the last Scipio of any consequence in Roman history."

Publius Licinius Crassus was one of two sons of Marcus Licinius Crassus, the so-called "triumvir", and Tertulla, daughter of Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus. He belonged to the last generation of Roman nobiles who came of age and began a political career before the collapse of the Republic. His peers included Marcus Antonius, Marcus Junius Brutus, Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, the poet Gaius Valerius Catullus, and the historian Gaius Sallustius Crispus.

Megabocchus was a friend and contemporary of Publius Crassus, son of the triumvir Marcus Crassus. He died at the Battle of Carrhae.

Publius Aquillius Gallus was a tribune of the plebs in 55 BC. With his colleague Gaius Ateius Capito, Aquillius Gallus opposed the Lex Trebonia and the plans regarding proconsular commands for Crassus and Pompeius. Crassus's war against Parthia resulted in one of the worst defeats ever suffered by a Roman army, the Battle of Carrhae.

The gens Coponia was a plebeian family at Rome. The family was prominent at Rome during the first century BC. The most famous of the gens may have been Gaius Coponius, praetor in 49 BC, and a partisan of Pompeius, whom although proscribed by the triumvirs in 43, was subsequently pardoned, and came to be regarded as a greatly respected member of the Senate.

The Tribune's Curse is a novel by John Maddox Roberts. It is the seventh volume of Roberts's SPQR series, featuring Senator Decius Metellus.

The gens Munatia was a plebeian family at Rome. Members of this gens are first mentioned during the second century BC, but they did not obtain any of the higher offices of the Roman state until imperial times.

The gens Roscia, probably the same as Ruscia, was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens are mentioned as early as the fifth century BC, but after this time they vanish into obscurity until the final century of the Republic. A number of Roscii rose to prominence in imperial times, with some attaining the consulship from the first to the third centuries.

The gens Trebonia, rarely Terebonia, was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens are mentioned in the first century of the Republic, and regularly throughout Roman history, but none of them attained the consulship until the time of Caesar.

References

- ↑ T.R.S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, vol. 2 (New York 1952), pp. 216 and 533.

- ↑ Pompeius and Crassus held their first consulship in 70 BC.

- ↑ Plutarch, Cato Minor 43; Cassius Dio 39.32.3 and 39.35–38.

- ↑ Robin Seager, Pompey the Great: A Political Biography (Blackwell Publishing, 2002, originally published 1979), 2nd edition, p. 124 online; Elaine Fantham, The Roman World of Cicero's De Oratore (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 233 online.

- ↑ Erich S. Gruen, "Pompey, the Roman Aristocracy, and the Conference of Luca," Historia 18 (1969) 71–108, especially 107–108. The literature on the triumvirate's political deal-making in 56 BC is vast; see for instance Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (Oxford University Press, 1939, reissued 2002), limited preview online, particularly Chapter 3, "The Domination of Pompeius"; J.P.V.D. Balsdon, "Consular Provinces under the Late Republic, II," Journal of Roman Studies 29 (1939) 167–183; Colm Luibheid, "The Luca Conference," Classical Philology 65 (1970) 88–94; and Anthony J. Marshall, review of Crassus: A Political Biography by B.A. Marshall (Amsterdam 1976) and Marcus Crassus and the Late Roman Republic by A.M. Ward (University of Missouri Press, 1977), Phoenix 32 (1978) 261–266.

- ↑ The case is discussed at length by C.F. Konrad, "Vellere signa," in Augusto Augurio (Franz Steiner, 2004), pp. 181–185 online.

- ↑ Plutarch, Crassus 16.5–6, from Sarah Iles Johnston, Religions of the Ancient World (Harvard University Press, 2004), p. 510 online (transl. Warner).

- ↑ Johnston, Religions of the Ancient World, p. 510.

- ↑ Cicero, De divination 1.29–30; Velleius Paterculus 2.46.3, on which see the commentary of A.J. Woodman (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 73 online; Plutarch, Crassus 16; Appian, Bellum civile 2.18; Florus 1.46.3. For more on the departure, see Cicero, Ad Atticum 4.13.2 and Ad familiares 1.9.20, and Lucan 3.43ff., as cited by Broughton, Magistrates of the Roman Republic, p. 216; see also Lucan 3,126-127.

- ↑ Ronald Syme, Sallust (University of California Press, 2002, originally published 1964), p. 34 online. The expulsion of Ateius was not unique; Appius conducted a thorough housecleaning, removing any man who was the son of a freedman and others such as the historian Sallust.

- ↑ Cicero, De divinatione 1.29–30; the case of Ateius discussed at some length in the commentary of David Wardle, Cicero on Divination (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2006), pp. 180–187 online.

- ↑ J. Gwyn Griffiths, The Divine Verdict: A Study of Divine Judgement in the Ancient Religions (Brill, 1991), p. 98 online.

- ↑ Cicero, Ad familiares 13.29.2, Ad Atticum 13.33.4 and 16.16.

- ↑ Cicero, Ad Atticum 16.16c, f

- Some information in this article was originally taken from Quien es quien en la Antigua Roma (Editions: Acento Editorial, 2002).