Freyr, sometimes anglicized as Frey, is a widely attested god in Norse mythology, associated with kingship, fertility, peace, prosperity, fair weather, and good harvest. Freyr, sometimes referred to as Yngvi-Freyr, was especially associated with Sweden and seen as an ancestor of the Swedish royal house. According to Adam of Bremen, Freyr was associated with peace and pleasure, and was represented with a phallic statue in the Temple at Uppsala. According to Snorri Sturluson, Freyr was "the most renowned of the æsir", and was venerated for good harvest and peace.

In Norse mythology, Freyja is a goddess associated with love, beauty, fertility, sex, war, gold, and seiðr. Freyja is the owner of the necklace Brísingamen, rides a chariot pulled by two cats, is accompanied by the boar Hildisvíni, and possesses a cloak of falcon feathers. By her husband Óðr, she is the mother of two daughters, Hnoss and Gersemi. Along with her twin brother Freyr, her father Njörðr, and her mother, she is a member of the Vanir. Stemming from Old Norse Freyja, modern forms of the name include Freya, Freyia, and Freja.

Frigg is a goddess, one of the Æsir, in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about her, she is associated with marriage, prophecy, clairvoyance and motherhood, and dwells in the wetland halls of Fensalir. In wider Germanic mythology, she is known in Old High German as Frīja, in Langobardic as Frēa, in Old English as Frīg, in Old Frisian as Frīa, and in Old Saxon as Frī, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Frijjō. Nearly all sources portray her as the wife of the god Odin.

In Norse mythology, Njörðr is a god among the Vanir. Njörðr, father of the deities Freyr and Freyja by his unnamed sister, was in an ill-fated marriage with the goddess Skaði, lives in Nóatún and is associated with the sea, seafaring, wind, fishing, wealth, and crop fertility.

In Norse mythology, the Vanir are a group of gods associated with fertility, wisdom, and the ability to see the future. The Vanir are one of two groups of gods and are the namesake of the location Vanaheimr. After the Æsir–Vanir War, the Vanir became a subgroup of the Æsir. Subsequently, members of the Vanir are sometimes also referred to as members of the Æsir.

In Norse mythology, Fólkvangr is a meadow or field ruled over by the goddess Freyja where half of those that die in combat go upon death, whilst the other half go to the god Odin in Valhalla. Others were also brought to Fólkvangr after their death; Egils Saga, for example, has a world-weary female character declare that she will never taste food again until she dines with Freyja. Fólkvangr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. According to the Prose Edda, within Fólkvangr is Freyja's hall Sessrúmnir. Scholarly theories have been proposed about the implications of the location.

In Norse mythology, Fensalir is a location where the goddess Frigg dwells. Fensalir is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the location, including that the location may have some connection to religious practices involving springs, bogs, or swamps in Norse paganism, and that it may be connected to the goddess Sága's watery location Sökkvabekkr.

Gullveig is a female figure in Norse mythology associated with the legendary conflict between the Æsir and Vanir. In the poem Völuspá, she came to the hall of Odin (Hár) where she is speared by the Æsir, burnt three times, and yet thrice reborn. Upon her third rebirth, she began practicing seiðr and took the name Heiðr.

In Norse mythology, Óðr or Óð, sometimes anglicized as Odr or Od, is a figure associated with the major goddess Freyja. The Prose Edda and Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, both describe Óðr as Freyja's husband and father of her daughter Hnoss. Heimskringla adds that the couple produced another daughter, Gersemi. A number of theories have been proposed about Óðr, generally that he is a hypostasis of the deity Odin due to their similarities.

The Frigg and Freyja common origin hypothesis holds that the Old Norse goddesses Frigg and Freyja descend from a common Proto-Germanic figure, as suggested by the numerous similarities found between the two deities. Scholar Stephan Grundy comments that "the problem of whether Frigg or Freyja may have been a single goddess originally is a difficult one, made more so by the scantiness of pre-Viking Age references to Germanic goddesses, and the diverse quality of the sources. The best that can be done is to survey the arguments for and against their identity, and to see how well each can be supported."

Germanic mythology consists of the body of myths native to the Germanic peoples, including Norse mythology, Anglo-Saxon mythology, and Continental Germanic mythology. It was a key element of Germanic paganism.

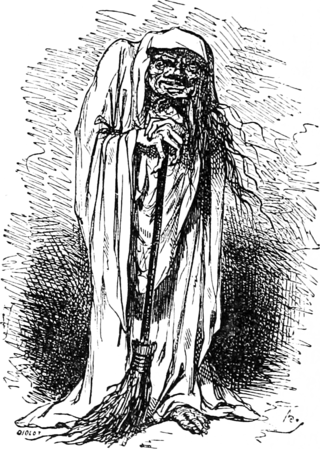

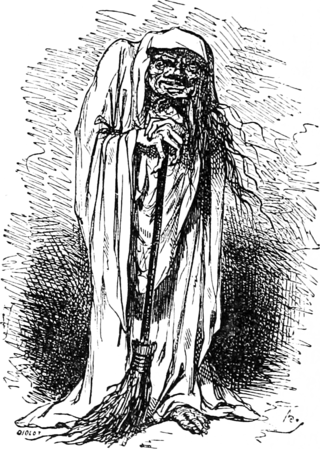

In Germanic paganism, a seeress is a woman said to have the ability to foretell future events and perform sorcery. They are also referred to with many other names meaning "prophetess", "staff bearer" and "sorceress", and they are frequently called witches both in early sources and in modern scholarship. In Norse mythology the seeress is usually referred to as völva or vala.

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, the Netherlands, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied. Scholars typically assume some degree of continuity between Roman-era beliefs and those found in Norse paganism, as well as between Germanic religion and reconstructed Indo-European religion and post-conversion folklore, though the precise degree and details of this continuity are subjects of debate. Germanic religion was influenced by neighboring cultures, including that of the Celts, the Romans, and, later, by the Christian religion. Very few sources exist that were written by pagan adherents themselves; instead, most were written by outsiders and can thus present problems for reconstructing authentic Germanic beliefs and practices.

The Origo Gentis Langobardorum is a short, 7th-century AD Latin account offering a founding myth of the Longobard people. The first part describes the origin and naming of the Lombards, the following text more resembles a king-list, up until the rule of Perctarit (672–688).

In Norse mythology, Sága is a goddess associated with the location Sökkvabekkr. At Sökkvabekkr, Sága and the god Odin merrily drink as cool waves flow. Both Sága and Sökkvabekkr are attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the goddess and her associated location, including that the location may be connected to the goddess Frigg's fen residence Fensalir and that Sága may be another name for Frigg.

Odin is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and depicts him as the husband of the goddess Frigg. In wider Germanic mythology and paganism, the god was also known in Old English as Wōden, in Old Saxon as Uuôden, in Old Dutch as Wuodan, in Old Frisian as Wêda, and in Old High German as Wuotan, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Wōðanaz, meaning 'lord of frenzy', or 'leader of the possessed'.

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology, is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern period. The northernmost extension of Germanic mythology and stemming from Proto-Germanic folklore, Norse mythology consists of tales of various deities, beings, and heroes derived from numerous sources from both before and after the pagan period, including medieval manuscripts, archaeological representations, and folk tradition. The source texts mention numerous gods such as the thunder-god Thor, the raven-flanked god Odin, the goddess Freyja, and numerous other deities.

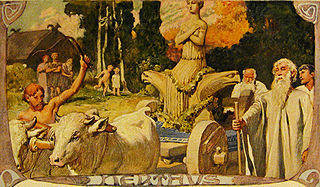

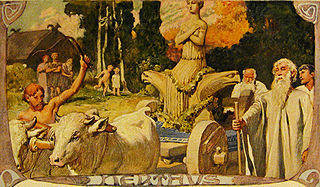

In Norse mythology, Gefjon is a goddess associated with ploughing, the Danish island of Zealand, the legendary Swedish king Gylfi, the legendary Danish king Skjöldr, foreknowledge, her oxen children, and virginity. Gefjon is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson; in the works of skalds; and appears as a gloss for various Greco-Roman goddesses in some Old Norse translations of Latin works.

*Frijjō ("Frigg-Frija") is the reconstructed name or epithet of a hypothetical Common Germanic love goddess, the most prominent female member of the *Ansiwiz (gods), and often identified as the spouse of the chief god, *Wōdanaz (Woden-Odin).

Haliurunas, haljarunae, Haliurunnas, haliurunnae, etc., were Gothic "witches" who appear once in Getica, a 6th century work on Gothic history. The account tells that the early Goth king Filimer found witches among his people when they had settled north of the Black Sea, and that he banished them to exile. They were impregnated by unclean spirits and engendered the Huns, and the account is a precursor of later Christian traditions where wise women were alleged to have sexual intercourse and even orgies with demons and the Devil.