Related Research Articles

Alboin was king of the Lombards from about 560 until 572. During his reign the Lombards ended their migrations by settling in Italy, the northern part of which Alboin conquered between 569 and 572. He had a lasting effect on Italy and the Pannonian Basin; in the former, his invasion marked the beginning of centuries of Lombard rule, and in the latter, his defeat of the Gepids and his departure from Pannonia ended the dominance there of the Germanic peoples.

The Lombards or Longobards were a Germanic people who conquered most of the Italian Peninsula between 568 and 774.

Paul the Deacon, also known as Paulus Diaconus, Warnefridus, Barnefridus, or Winfridus, and sometimes suffixed Cassinensis, was a Benedictine monk, scribe, and historian of the Lombards.

Menia was the queen of the Thuringians by marriage and the earliest named ancestor of the Gausian dynasty of the Lombards. She became a legendary figure after her death, strongly associated with gold and wealth.

Tato was an early 6th century king of the Lombards. He was the son of Claffo and a king of the Lething Dynasty. According to Procopius, the Lombards were subject and paid tribute to the Heruli during his reign. In 508, he fought with King Rodulf of the Heruli, who was slain. This was a devastating blow to the Heruli and augmented the power of the Lombards. According to Paul the Deacon, the war started because Tato's daughter Rumetrada murdered Rodulf's brother.

Alduin was king of the Lombards from 547 to 560.

The Origo Gentis Langobardorum is a short, 7th-century AD Latin account offering a founding myth of the Longobard people. The first part describes the origin and naming of the Lombards, the following text more resembles a king-list, up until the rule of Perctarit (672–688).

The Rule of the Dukes was an interregnum in the Lombard Kingdom of Italy (574/5–584/5) during which Italy was ruled by the Lombard dukes of the old Roman provinces and urban centres. The interregnum is said to have lasted a decade according to Paul the Deacon, but all other sources—the Fredegarii Chronicon, the Origo Gentis Langobardorum, the Chronicon Gothanum, and the Copenhagen continuator of Prosper Tiro—accord it twelve years. Here is how Paul describes the dukes' rule:

After his death the Langobards had no king for ten years but were under dukes, and each one of the dukes held possession of his own city, Zaban of Ticinum, Wallari of Bergamus, Alichis of Brexia, Euin of Tridentum, Gisulf of Forum Julii. But there were thirty other dukes besides these in their own cities. In these days many of the noble Romans were killed from love of gain, and the remainder were divided among their "guests" and made tributaries, that they should pay the third part of their products to the Langobards. By these dukes of the Langobards in the seventh year from the coming of Alboin and of his whole people, the churches were despoiled, the priests killed, the cities overthrown, the people who had grown up like crops annihilated, and besides those regions which Alboin had taken, the greater part of Italy was seized and subjugated by the Langobards.

The Kingdom of the Lombards, also known as the Lombard Kingdom and later as the Kingdom of all Italy, was an early medieval state established by the Lombards, a Germanic people, on the Italian Peninsula in the latter part of the 6th century. The king was traditionally elected by the very highest-ranking aristocrats, the dukes, as several attempts to establish a hereditary dynasty failed. The kingdom was subdivided into a varying number of duchies, ruled by semi-autonomous dukes, which were in turn subdivided into gastaldates at the municipal level. The capital of the kingdom and the center of its political life was Pavia in the modern northern Italian region of Lombardy.

The Duchy of Friuli was a Lombard duchy in present-day Friuli, the first to be established after the conquest of the Italian peninsula in 568. It was one of the largest domains in Langobardia Major and an important buffer between the Lombard kingdom and the Slavs, Avars, and the Byzantine Empire. The original chief city in the province was Roman Aquileia, but the Lombard capital of Friuli was Forum Julii, modern Cividale.

Andreas of Bergamo was an Italian historian of the late ninth century. He composed a continuation of the Historia Langobardorum of Paul the Deacon down to ca. 877. The short continuation, untitled in the manuscripts, is sometimes called the Andreæ presbyteri Bergomatis chronicon. All that is known of Andreas is that he was a priest of the diocese of Bergamo that he helped carry the coffin of the Emperor Louis II from the river Oglio as far as the Adda in 875. However, he never says that he was from Bergamo and he never identifies himself as either a Lombard or a Frank.

Waldrada (531–572), wife (firstly) of Theudebald, King of Austrasia, reputed mistress (secondly) of Chlothar I, King of the Franks, was the daughter of Wacho, King of the Lombards and his second wife called Austrigusa or Ostrogotha, a Gepid.

The Codex Gothanus 84 is a 10th/11th century Latin law parchment manuscript in two-column Carolingian minuscule and is one of two extant copies of a lost early ninth-century codex written at Fulda and commissioned by Eberhard of Friuli, probably about 830, from the scholar Lupus Servatus, abbot of Ferrières. It is held by the Gotha Research Library, hence its name.

Bisinus was the king of Thuringia in the 5th century AD or around 500. He is the earliest historically attested ruler of the Thuringians. Almost nothing more about him can be said with certainty, including whether all the variations on his name in the sources refer to one or two different persons. His name is given as Bysinus, Bessinus or Bissinus in Frankish sources, and as Pissa, Pisen, Fisud or Fisut in Lombard ones.

Cunimund was the last king of the Gepids, falling in the Lombard–Gepid War (567) against the Lombards and Pannonian Avars.

Among the Lombards, the duke or dux was the man who acted as political and military commander of a set of "military families", irrespective of any territorial appropriation.

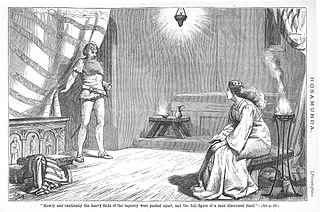

Helmichis was a Lombard noble who killed his king, Alboin, in 572 and unsuccessfully attempted to usurp his throne. Alboin's queen, Rosamund, supported or at least did not oppose Helmichis' plan to remove the king, and after the assassination Helmichis married her. The assassination was assisted by Peredeo, the king's chamber-guard, who in some sources becomes the material executer of the murder. Helmichis is first mentioned by the contemporary chronicler Marius of Avenches, but the most detailed account of his endeavours derives from Paul the Deacon's late 8th-century Historia Langobardorum.

Thurisind was king of the Gepids, an East Germanic Gothic people, from c. 548 to 560. He was the penultimate Gepid king, and succeeded King Elemund by staging a coup d'état and forcing the king's son into exile. Thurisind's kingdom, known as Gepidia, was located in Central Europe and had its centre in Sirmium, a former Roman city on the Sava River.

In 566, Lombard king Alboin concluded a treaty with the Pannonian Avars, to whom he promised the Gepids' land if they defeated them. The Gepids were destroyed by the Avars and the Lombards in 567. Gepid King Cunimund was killed by Alboin himself. The Avars subsequently occupied "Gepidia", forming the Avar Khaganate. The Byzantine Emperor intervened and took control of Sirmium, also giving refuge to Gepid leader Usdibad, although the rest of Gepidia was taken by the Avars. Gepid military strength was significantly reduced; according to H. Schutz (2001) many of them joined Lombard ranks, while the rest took to Constantinople. According to R. Collins (2010) the remnants were absorbed either by the Avars or Lombards. Although later Lombard sources claim they had a central role in this war, it is clear from contemporary Byzantine sources that the Avars had the principal role. The Gepids disappeared and the Avars took their place as a Byzantine threat. The Lombards disliked their new neighbours and decided to leave for Italy, forming the Kingdom of the Lombards.

References

Notes

- ↑ Chronicon Gothanum means "chronicle from Gotha", and Historia Langobardorum codicis Gothani means "history of the Lombards from the codex of Gotha".

Citations

- ↑ "Gotha, Forschungsbibliothek, Memb. I 84". Capitularia - Edition der fränkischen Herrschererlasse.

- 1 2 Everett (2003), 93–94.

- ↑ Igitur Corsicam insulam a Mauris oppressam suo iussu eiusque exercitus liberavit, quoted in Berto (2010), 28 n. 30.

- ↑ "That same year, against the Moors on the island of Corsica—which they had devastated—Pippin sent a fleet from Italy, the arrival of which the Moors did not expect and retreated" (Eodem anno in Corsicam insulam contra Mauros, qui eam vastabant, classis de Italia a Pippino missa est, cuius adventum Mauri non espectantes abscesserunt), quoted in Berto (2010), 28 n. 30.

- ↑ "This present day by his [Pippin's] help Italy shines, as in ancient days. Law, harvests, peace and quiet she has. . ." (Praesentem diem per eius adiutorium splenduit Italia, sicut fecit antiquissimis diebus. Leges et ubertates et quietudinem habuit. . .), quoted in Berto (2010), 28 n. 31.

- 1 2 Berto (2010), 28.

- ↑ "So after struggling they arrived in the Saxon country, at the place called Patespruna (Paderborn); where our ancient fathers assert they lived a long time" (sic deinde certantes Saxoni patria attigerunt, locus ubi Patespruna cognominantur; ubi sicut nostri antiqui patres longo tempore asserunt habitasse), quoted in Berto (2010), 29 n. 33.

- ↑ "Thus, even to this present day the remains of King Wacho's palace and residence are visible" (Unde usque hodie presentem diem Wachoni regi eorum domus et habitatio apparet signa), quoted in Berto (2010), 29 n. 34.

- ↑ Berto (2010), 29 n. 34.

- ↑ Berto (2010), 48.

- ↑ Everett (2003), 93, citing Azzara, Claudio; Gasparri, Stefano, eds. (1992). Le leggi dei Longobardi: storia, memoria e diritto di un popolo germanico (in Italian). Milano: Editrice La Storia. pp. 282–291. ISBN 88-86156-00-6..

- ↑ Everett (2003), 94, citing Bracciotti, Origo gentis langobardorum: introduzione, testo critico, commento, Biblioteca di Cultura Romanobarbarica 2 (Rome: 1998), 14. A "subarchetype" or "hyperarchetype" is a hypothesised or reconstructed version of a text lying between the original archetype and the final version.

- ↑ Berto (2010), 28, citing Cingolani, Le storie dei Longobardi: dall'origine a Paolo Diacono (Rome: 1995), 94.

- ↑ Goffart (1988), 382 n. 163.

- ↑ Goffart (1988), 390 n. 191.

- ↑ Learned (1892), 173.

- ↑ Istius rothari regis temporibus ortum est lumen in tenebris; per quem supradicti langobardi ad cannonicam tenderunt certamina et sacerdotum facti sunt adiutores, quoted in Everett (2003), 170 n. 30, for whom the phrase "helpers of priests" is "curiously Carolingian".

- ↑ Goffart (1988), 393 n. 201.

- ↑ Berto (2010), 31 and n. 44.

- ↑ Non inputatur peccatum, cum lex non esset, quoted in Berto (2010), 32.

- ↑ Berto (2010), 33.

- ↑ Berto (2010), 34–35.

- ↑ Berto (2010), 38.

- ↑ Berto (2010), 49 n. 137, summarises Coumert's argument, but disagrees with it.

Works cited

- Berto, Luigi Andrea. "Remembering Old and New Rulers: Lombards and Carolingians in Carolingian Italian Memory". The Medieval History Journal13, 1 (2010): 23–53.

- Everett, Nicholas. Literacy in Lombard Italy, c. 568–774. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Goffart, Walter. The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550–800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Learned, Marion Dexter. "Origin and Development of the Walther Saga" Publication of the Modern Language Association7, 1 (1892): 131–95.