Ovintiv Inc. is an American petroleum company based in Denver. The company was formed in 2020 through a restructuring of its Canadian predecessor, Encana.

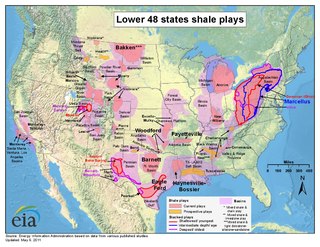

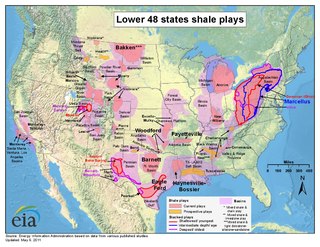

The Barnett Shale is a geological formation located in the Bend Arch-Fort Worth Basin. It consists of sedimentary rocks dating from the Mississippian period in Texas. The formation underlies the city of Fort Worth and underlies 5,000 mi2 (13,000 km2) and at least 17 counties.

Fracking in the United States began in 1949. According to the Department of Energy (DOE), by 2013 at least two million oil and gas wells in the US had been hydraulically fractured, and that of new wells being drilled, up to 95% are hydraulically fractured. The output from these wells makes up 43% of the oil production and 67% of the natural gas production in the United States. Environmental safety and health concerns about hydraulic fracturing emerged in the 1980s, and are still being debated at the state and federal levels.

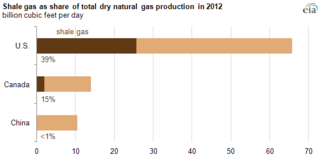

Shale gas is an unconventional natural gas that is found trapped within shale formations. Since the 1990s a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has made large volumes of shale gas more economical to produce, and some analysts expect that shale gas will greatly expand worldwide energy supply.

Well stimulation is a broad term used to describe the various techniques and well interventions that can be used to restore or enhance the production of hydrocarbons from an oil well.

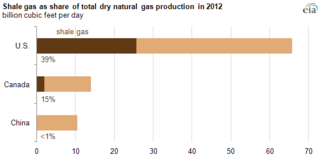

Shale gas in the United States is an available source of unconventional natural gas. Led by new applications of hydraulic fracturing technology and horizontal drilling, development of new sources of shale gas has offset declines in production from conventional gas reservoirs, and has led to major increases in reserves of U.S. natural gas. Largely due to shale gas discoveries, estimated reserves of natural gas in the United States in 2008 were 35% higher than in 2006.

Ann McElhinney and Phelim McAleer are conservative Irish documentary filmmakers and New York Times best-selling authors. They have written and produced the political documentaries FrackNation, Not Evil Just Wrong, and Mine Your Own Business, as well as The Search for Tristan's Mum and Return to Sender. Their latest project, Gosnell: The Trial of America's Biggest Serial Killer, is a true crime drama film based on the crimes of Kermit Gosnell. Their book, Gosnell: The Untold Story of America’s Most Prolific Serial Killer, was an Amazon and New York Times best seller. They were married at the Basilica Church of St Mary Magdalene in Dublin in 1992.

Josh Fox is an American film director, playwright and environmental activist, best known for his Oscar-nominated, Emmy-winning 2010 documentary, Gasland. He is the founder and artistic director of a film and theater company in New York City, International WOW, and has contributed as a journalist to Rolling Stone, The Daily Beast, NowThis, AJ+ and Huffington Post.

The inclusion of unconventional shale gas with conventional gas reserves has caused a sharp increase in estimated recoverable natural gas in Canada. Until the 1990s success of hydraulic fracturing in the Barnett Shales of north Texas, shale gas was classed as "unconventional reserves" and was considered too expensive to recover. There are a number of prospective shale gas deposits in various stages of exploration and exploitation across the country, from British Columbia to Nova Scotia.

Fracking is a well stimulation technique involving the fracturing of formations in bedrock by a pressurized liquid. The process involves the high-pressure injection of "fracking fluid" into a wellbore to create cracks in the deep-rock formations through which natural gas, petroleum, and brine will flow more freely. When the hydraulic pressure is removed from the well, small grains of hydraulic fracturing proppants hold the fractures open.

Fracking in the United Kingdom started in the late 1970s with fracturing of the conventional oil and gas fields near the North Sea. It was used in about 200 British onshore oil and gas wells from the early 1980s. The technique attracted attention after licences use were awarded for onshore shale gas exploration in 2008. The topic received considerable public debate on environmental grounds, with a 2019 high court ruling ultimately banning the process. The two remaining high-volume fracturing wells were supposed to be plugged and decommissioned in 2022.

FrackNation is a feature documentary created by Phelim McAleer, Ann McElhinnery, and Magdalena Segieda. The film, released in 2013, claims to address alleged misinformation from environmentalists about the process of hydraulic fracturing, commonly called fracking.

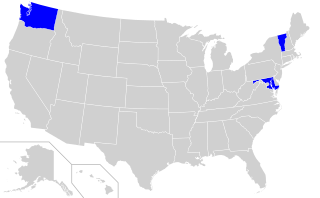

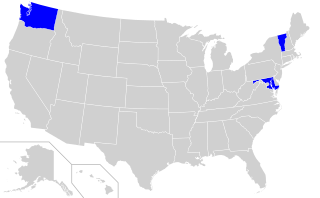

Fracking has become a contentious environmental and health issue with Tunisia and France banning the practice and a de facto moratorium in place in Quebec (Canada), and some of the states of the US.

Environmental impact of fracking in the United States has been an issue of public concern, and includes the contamination of ground and surface water, methane emissions, air pollution, migration of gases and fracking chemicals and radionuclides to the surface, the potential mishandling of solid waste, drill cuttings, increased seismicity and associated effects on human and ecosystem health. Research has determined that human health is affected. A number of instances with groundwater contamination have been documented due to well casing failures and illegal disposal practices, including confirmation of chemical, physical, and psychosocial hazards such as pregnancy and birth outcomes, migraine headaches, chronic rhinosinusitis, severe fatigue, asthma exacerbations, and psychological stress. While opponents of water safety regulation claim fracking has never caused any drinking water contamination, adherence to regulation and safety procedures is required to avoid further negative impacts.

The environmental impact of fracking is related to land use and water consumption, air emissions, including methane emissions, brine and fracturing fluid leakage, water contamination, noise pollution, and health. Water and air pollution are the biggest risks to human health from fracking. Research has determined that fracking negatively affects human health and drives climate change.

There are many exemptions for fracking under United States federal law: the oil and gas industries are exempt or excluded from certain sections of a number of the major federal environmental laws. These laws range from protecting clean water and air, to preventing the release of toxic substances and chemicals into the environment: the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, National Environmental Policy Act, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, commonly known as Superfund.

The anti-fracking movement is a political movement that seeks to ban the practice of extracting natural gasses from shale rock formations to provide power due to its negative environmental impact. These effects include the contamination of drinking water, disruption of ecosystems, and adverse effects on human and animal health. Additionally, the practice of fracking increases the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere, escalating the process of climate change and global warming. An anti-fracking movement has emerged both internationally, with involvement of international environmental organizations, and nation states such as France and locally in affected areas such as Balcombe, Sussex, in the UK. Pungești in Romania, Žygaičiai in Lithuania, and In Salah in Algeria. Through the use of direct action, media, and lobbying, the anti-fracking movement is focused on holding the gas and oil industry accountable for past and potential environmental damage, extracting compensation from and taxation of the industry to mitigate impact, and regulation of gas development and drilling activity.

The Marcellus natural gas trend is a large geographic area of prolific shale gas extraction from the Marcellus Shale or Marcellus Formation, of Devonian age, in the eastern United States. The shale play encompasses 104,000 square miles and stretches across Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and into eastern Ohio and western New York. In 2012, it was the largest source of natural gas in the United States, and production was still growing rapidly in 2013. The natural gas is trapped in low-permeability shale, and requires the well completion method of hydraulic fracturing to allow the gas to flow to the well bore. The surge in drilling activity in the Marcellus Shale since 2008 has generated both economic benefits and considerable controversy.

Fracking in Canada was first used in Alberta in 1953 to extract hydrocarbons from the giant Pembina oil field, the biggest conventional oil field in Alberta, which would have produced very little oil without fracturing. Since then, over 170,000 oil and gas wells have been fractured in Western Canada. Fracking is a process that stimulates natural gas or oil in wellbores to flow more easily by subjecting hydrocarbon reservoirs to pressure through the injection of fluids or gas at depth causing the rock to fracture or to widen existing cracks.