Charles Pierre Baudelaire was a French poet who also worked as an essayist, art critic and translator. His poems are described as exhibiting mastery of rhyme and rhythm, containing an exoticism inherited from Romantics, and are based on observations of real life.

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier was a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, and art and literary critic.

Louise Charlin Perrin Labé,, also identified as La Belle Cordière, was a feminist French poet of the Renaissance born in Lyon, the daughter of wealthy ropemaker Pierre Charly and his second wife, Etiennette Roybet.

Frédéric-Louis Sauser, better known as Blaise Cendrars, was a Swiss-born novelist and poet who became a naturalized French citizen in 1916. He was a writer of considerable influence in the European modernist movement.

Gérard de Nerval was the pen name of the French writer, poet, and translator Gérard Labrunie, a major figure of French romanticism, best known for his novellas and poems, especially the collection Les Filles du feu, which included the novella Sylvie and the poem "El Desdichado". Through his translations, Nerval played a major role in introducing French readers to the works of German Romantic authors, including Klopstock, Schiller, Bürger and Goethe. His later work merged poetry and journalism in a fictional context and influenced Marcel Proust. His last novella, Aurélia ou le rêve et la vie, influenced André Breton and Surrealism.

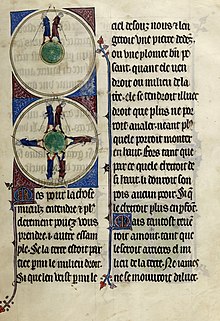

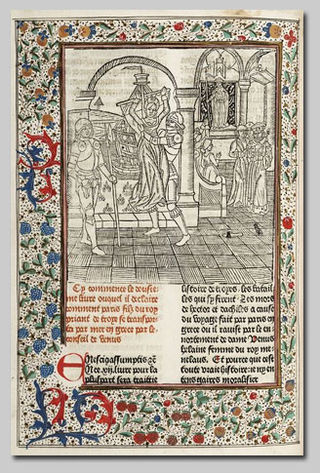

Le Roman de la Rose is a medieval poem written in Old French and presented as an allegorical dream vision. As poetry, The Romance of the Rose is a notable instance of courtly literature, purporting to provide a "mirror of love" in which the whole art of romantic love is disclosed. Its two authors conceived it as a psychological allegory; throughout the Lover's quest, the word Rose is used both as the name of the titular lady and as an abstract symbol of female sexuality. The names of the other characters function both as personal names and as metonyms illustrating the different factors that lead to and constitute a love affair. Its long-lasting influence is evident in the number of surviving manuscripts of the work, in the many translations and imitations it inspired, and in the praise and controversy it inspired.

This article presents lists of the literary events and publications in the 15th century.

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of diverse origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The Golden Legend is a collection of 153 hagiographies by Jacobus de Voragine that was widely read in Europe during the Late Middle Ages. More than a thousand manuscripts of the text have survived. It was likely compiled around 1259–1266, although the text was added to over the centuries.

Le Morte d'Arthur is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the Round Table, along with their respective folklore. In order to tell a "complete" story of Arthur from his conception to his death, Malory compiled, rearranged, interpreted and modified material from various French and English sources. Today, this is one of the best-known works of Arthurian literature. Many authors since the 19th-century revival of the legend have used Malory as their principal source.

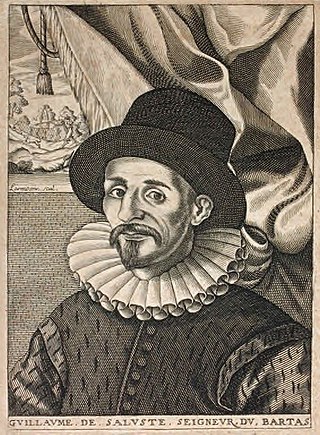

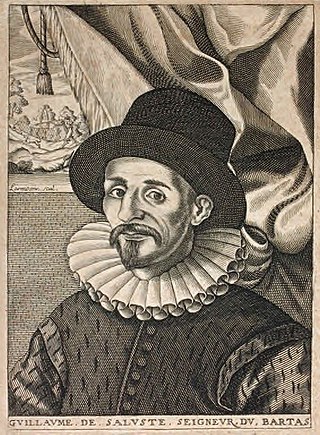

Guillaume de Salluste Du Bartas was a Gascon Huguenot courtier and poet. Trained as a doctor of law, he served in the court of Henri de Navarre for most of his career. Du Bartas was celebrated across sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe for his divine poetry, particularly L'Uranie (1574), Judit (1574), La Sepmaine; ou, Creation du monde (1578), and La Seconde Semaine (1584-1603).

The medieval genre of speculum literature, popular from the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries, was inspired by the urge to encompass encyclopedic knowledge within a single work. However, some of these works have a restricted scope and function as instructional manuals. In this sense the encyclopedia and the speculum are similar, but they are not the same genre.

Cosmographia ("Cosmography"), also known as De mundi universitate, is a Latin philosophical allegory, dealing with the creation of the universe, by the twelfth-century author Bernardus Silvestris. In form, it is a prosimetrum, in which passages of prose alternate with verse passages in various classical meters. The philosophical basis of the work is the Platonism of contemporary philosophers associated with the cathedral school of Chartres—one of whom, Thierry of Chartres, is the dedicatee of the work. According to a marginal note in one early manuscript, the Cosmographia was recited before Pope Eugene III when he was traveling in France (1147–48).

Colard Mansion was a 15th-century Flemish scribe and printer who worked together with William Caxton. He is known as the first printer of a book with copper engravings, and as the printer of the first books in English and French.

Dicts and Sayings of the Philosophers is an incunabulum, or early printed book. The Middle English work is a translation, by Anthony Woodville, of a wisdom literature compendium written in Arabic by the medieval Arab scholar al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik, titled Mukhtār al-ḥikam wa-maḥāsin al-kalim which had been translated into several languages. Woodville based his version on an earlier French translation. His translation would come to be printed by William Caxton in 1477 as either the first, or one of the earliest, books printed in the English language.

The Cock and the Jewel is a fable attributed to Aesop and is numbered 503 in the Perry Index. As a trope in literature, the fable is reminiscent of stories used in Zen such as the kōan. It presents, in effect, a riddle on relative values and is capable of different interpretations, depending on the point of view from which it is regarded.

Andrew Chertsey was an English translator, now known for the devotional collection The craft to lyve well and to dye.

The Mountain in Labour is one of Aesop's Fables and appears as number 520 in the Perry Index. The story became proverbial in Classical times and was applied to a variety of situations. It refers to speech acts which promise much but deliver little, especially in literary and political contexts. In more modern times the satirical intention behind the fable was given greater emphasis following Jean de la Fontaine's interpretation of it. Illustrations to the text underlined its ironical application particularly and went on to influence cartoons referring to the fable elsewhere in Europe and America.

The Old English Boethius is an Old English translation/adaptation of the sixth-century Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, dating from between c. 880 and 950. Boethius's work is prosimetrical, alternating between prose and verse, and one of the two surviving manuscripts of the Old English translation renders the poems as Old English alliterative verse: these verse translations are known as the Metres of Boethius.

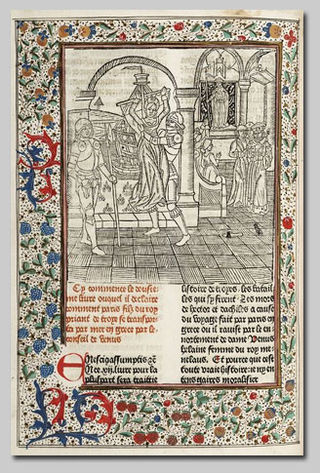

Jean de Vignay (c. 1282/1285 – c. 1350) was a French monk and translator. He translated from Latin into Old French for the French court, and his works survive in many illuminated manuscripts. They include two military manuals, a book on chess, parts of the New Testament, a travelogue and a chronicle.