Saint Helena is an island in the South Atlantic Ocean, about midway between South America and Africa. St Helena has a land area of 122 square kilometres and is part of the territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha which includes Ascension Island and the island group of Tristan da Cunha.

Rhyolite is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals (phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained groundmass. The mineral assemblage is predominantly quartz, sanidine, and plagioclase. It is the extrusive equivalent of granite.

The Galápagos Islands are an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Eastern Pacific, located around the Equator 900 km (560 mi) west of South America. They form the Galápagos Province of the Republic of Ecuador, with a population of slightly over 33,000 (2020). The province is divided into the cantons of San Cristóbal, Santa Cruz, and Isabela, the three most populated islands in the chain. The Galápagos are famous for their large number of endemic species, which were studied by Charles Darwin in the 1830s and inspired his theory of evolution by means of natural selection. All of these islands are protected as part of Ecuador's Galápagos National Park and Marine Reserve.

Dacite is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite. It is composed predominantly of plagioclase feldspar and quartz.

Trachyte is an extrusive igneous rock composed mostly of alkali feldspar. It is usually light-colored and aphanitic (fine-grained), with minor amounts of mafic minerals, and is formed by the rapid cooling of lava enriched with silica and alkali metals. It is the volcanic equivalent of syenite.

Phonolite is an uncommon shallow intrusive or extrusive rock, of intermediate chemical composition between felsic and mafic, with texture ranging from aphanitic (fine-grained) to porphyritic (mixed fine- and coarse-grained). Phonolite is a variation of the igneous rock trachyte that contains nepheline or leucite rather than quartz. It has an unusually high (12% or more) Na2O + K2O content, defining its position in the TAS classification of igneous rocks. Its coarse grained (phaneritic) intrusive equivalent is nepheline syenite. Phonolite is typically fine grained and compact. The name phonolite comes from the Ancient Greek meaning "sounding stone" due to the metallic sound it produces if an unfractured plate is hit; hence, the English name clinkstone is given as a synonym.

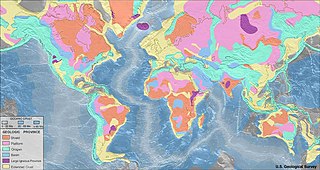

Volcanic rocks are rocks formed from lava erupted from a volcano. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic rock is artificial, and in nature volcanic rocks grade into hypabyssal and metamorphic rocks and constitute an important element of some sediments and sedimentary rocks. For these reasons, in geology, volcanics and shallow hypabyssal rocks are not always treated as distinct. In the context of Precambrian shield geology, the term "volcanic" is often applied to what are strictly metavolcanic rocks. Volcanic rocks and sediment that form from magma erupted into the air are called "pyroclastics," and these are also technically sedimentary rocks.

A shield volcano is a type of volcano named for its low profile, resembling a shield lying on the ground. It is formed by the eruption of highly fluid lava, which travels farther and forms thinner flows than the more viscous lava erupted from a stratovolcano. Repeated eruptions result in the steady accumulation of broad sheets of lava, building up the shield volcano's distinctive form.

Darwin's finches are a group of about 18 species of passerine birds. They are well known for their remarkable diversity in beak form and function. They are often classified as the subfamily Geospizinae or tribe Geospizini. They belong to the tanager family and are not closely related to the true finches. The closest known relative of the Galápagos finches is the South American dull-coloured grassquit. They were first collected when the second voyage of the Beagle visited the Galápagos Islands, with Charles Darwin on board as a gentleman naturalist. Apart from the Cocos finch, which is from Cocos Island, the others are found only on the Galápagos Islands.

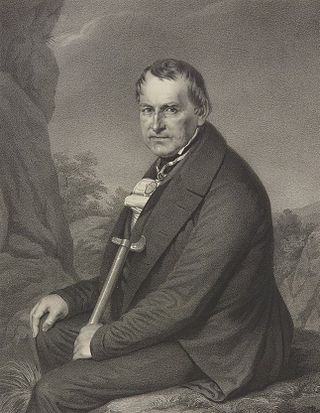

Christian Leopold von Buch, usually cited as Leopold von Buch, was a German geologist and paleontologist born in Stolpe an der Oder and is remembered as one of the most important contributors to geology in the first half of the nineteenth century. His scientific interest was devoted to a broad spectrum of geological topics: volcanism, petrology, fossils, stratigraphy and mountain formation. His most remembered accomplishment is the scientific definition of the Jurassic system.

Tachylite is a form of basaltic volcanic glass. This glass is formed naturally by the rapid cooling of molten basalt. It is a type of mafic igneous rock that is decomposable by acids and readily fusible. The color is a black or dark-brown, and it has a greasy-looking, resinous luster. It is very brittle and occurs in dikes, veins, and intrusive masses. The word originates from the Ancient Greek ταχύς, meaning "swift".

A volcanic plug, also called a volcanic neck or lava neck, is a volcanic object created when magma hardens within a vent on an active volcano. When present, a plug can cause an extreme build-up of high gas pressure if rising volatile-charged magma is trapped beneath it, and this can sometimes lead to an explosive eruption. In a plinian eruption the plug is destroyed and ash is ejected.

Santiago Island is one of the Galápagos Islands. The island, which consists of two overlapping volcanoes, has an area of 585 square kilometers (226 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 907 meters (2,976 ft), atop the northwestern shield volcano. The volcano in the island's southeast erupted along a linear fissure and is much lower. The oldest lava flows on the island date back to 750,000 years ago.

Floreana Island is a southern island in Ecuador's Galápagos Archipelago. The island has an area of 173 km2 (67 sq mi). It was formed by volcanic eruption. The island's highest point is Cerro Pajas at 640 m (2,100 ft), which is also the highest point of the volcano like most of the smaller islands of Galápagos. The island has a population of about 100.

Wolf Island is a small island in the northern Galápagos Islands. It has an area of 1.3 km2 (0.5 sq mi) and a maximum altitude of 253 m (830 ft) above sea level. The island is remote from the main archipelago and has no permanent population. The Galápagos National Park does not allow landing on the island; however, it is a popular diving location.

The second voyage of HMS Beagle, from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836, was the second survey expedition of HMS Beagle, made under her newest commander, Robert FitzRoy. FitzRoy had thought of the advantages of having someone onboard who could investigate geology, and sought a naturalist to accompany them as a supernumerary. At the age of 22, the graduate Charles Darwin hoped to see the tropics before becoming a parson, and accepted the opportunity. He was greatly influenced by reading Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology during the voyage. By the end of the expedition, Darwin had made his name as a geologist and fossil collector, and the publication of his journal gave him wide renown as a writer.

The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs, Being the first part of the geology of the voyage of the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Fitzroy, R.N. during the years 1832 to 1836, was published in 1842 as Charles Darwin's first monograph, and set out his theory of the formation of coral reefs and atolls. He conceived of the idea during the voyage of the Beagle while still in South America, before he had seen a coral island, and wrote it out as HMS Beagle crossed the Pacific Ocean, completing his draft by November 1835. At the time there was great scientific interest in the way that coral reefs formed, and Captain Robert FitzRoy's orders from the Admiralty included the investigation of an atoll as an important scientific aim of the voyage. FitzRoy chose to survey the Keeling Islands in the Indian Ocean. The results supported Darwin's theory that the various types of coral reefs and atolls could be explained by uplift and subsidence of vast areas of the Earth's crust under the oceans.

Igneous rock, or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

Geological Observations on South America is a book written by the English naturalist Charles Darwin. The book was published in 1846, and is based on his travels during the second voyage of HMS Beagle, commanded by captain Robert FitzRoy. HMS Beagle arrived in South America to map out the coastlines and islands of the region for the British Navy. On the journey, Darwin collected fossils and plants, and recorded the continent's geological features.

São Tomé and Príncipe both formed within the past 30 million years due to volcanic activity in deep water along the Cameroon line. Long-running interactions with seawater and different eruption periods have generated a wide variety of different igneous and volcanic rocks on the islands with complex mineral assemblages.