Macedonians are a nation and a South Slavic ethnic group native to the region of Macedonia in Southeast Europe. They speak Macedonian, a South Slavic language. The large majority of Macedonians identify as Eastern Orthodox Christians, who share a cultural and historical "Orthodox Byzantine–Slavic heritage" with their neighbours. About two-thirds of all ethnic Macedonians live in North Macedonia and there are also communities in a number of other countries.

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Georgi Nikolov Delchev, known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev, was an important Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji), active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions at the turn of the 20th century. He was the most prominent leader of what is known today as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a secret revolutionary society that was active in Ottoman territories in the Balkans at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Delchev was its representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria. As such, he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), participating in the work of its governing body. He was killed in a skirmish with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising.

Krste Petkov Misirkov was a philologist, journalist, historian and ethnographer from the region of Macedonia.

Kruševo is a town in North Macedonia. In Macedonian the name means the 'place of pear trees'. It is the highest town in North Macedonia and one of the highest in the Balkans, situated at an altitude of over 1350 m above sea level. The town of Kruševo is the seat of Kruševo Municipality. It is located in the western part of the country, overlooking the region of Pelagonia, 33 and 53 km from the nearby cities of Prilep and Bitola, respectively.

The history of the Macedonian language refers to the developmental periods of current-day Macedonian, an Eastern South Slavic language spoken on the territory of North Macedonia. The Macedonian language developed during the Middle Ages from the Old Church Slavonic, the common language spoken by Slavic people.

Dimo Hadzhidimov was a 20th-century Bulgarian teacher, revolutionary and politician from Ottoman Macedonia. He was among the leaders of the left wing of Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which he considered a Bulgarian creation.

Theodosius of Skopje was a Bulgarian religious figure from Macedonia who was also a scholar and translator of the Bulgarian language. He was initially involved in the struggle for an autonomous Bulgarian Church and later in his life, he became a member of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. Although he was named Metropolitan Bishop of the Bulgarian Exarchate in Skopje, he is known for his failed attempt to establish a separate Macedonian Church as a restoration of the Archbishopric of Ohrid. Theodosius of Skopje is considered a Bulgarian in Bulgaria and an ethnic Macedonian in North Macedonia.

Parteniy Zografski or Parteniy Nishavski was a 19th-century Bulgarian cleric, philologist, and folklorist from Galičnik in today's North Macedonia, one of the early figures of the Bulgarian National Revival. In his works he referred to his language as Bulgarian and demonstrated a Bulgarian spirit, though besides contributing to the development of the Bulgarian language, in North Macedonia he is also thought to have contributed to the codification of present-day Macedonian.

Macedonians or Macedonian Bulgarians, sometimes also referred to as Macedono-Bulgarians, Macedo-Bulgarians, or Bulgaro-Macedonians are a regional, ethnographic group of ethnic Bulgarians, inhabiting or originating from the region of Macedonia. Today, the larger part of this population is concentrated in Blagoevgrad Province but much is spread across the whole of Bulgaria and the diaspora.

Mijaks are an ethnographic group of Macedonians who live in the Lower Reka region which is also known as Mijačija, along the Radika river, in western North Macedonia, numbering 30,000–60,000 people. The Mijaks practise predominantly animal husbandry, and are known for their ecclesiastical architecture, woodworking, iconography, and other rich traditions, as well as their characteristic Galičnik dialect of Macedonian. The main settlement of the Mijaks is Galičnik.

Temko Popov was a pro-Macedonian activist and Serbian national worker in the Ottoman Empire. He espoused in his youth, according to Bulgarian sources, developed a kind of Macedonian pro-Serbian identity. Per Serbian sources, this plan was used by Serbian politicians as a counterweight to Bulgarian influence and to serbianize the Macedonian Slavs.

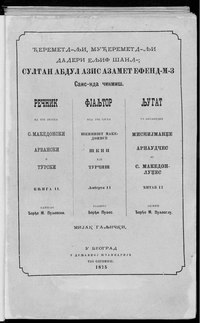

Bulgarian Folk Songs is a collection of folk songs and traditions from the then Ottoman Empire, especially from the region of Macedonia, but also from Shopluk and Srednogorie, published in 1861 by the Miladinov brothers. The Miladinovs' collection remains one of the greatest single works in the history of Bulgarian folklore studies and has been republished many times. The collection is considered also to have played an important role by the historiography in North Macedonia.

The Macedonian-Adrianople Social Democratic Group was a regional faction of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party in the Ottoman Empire. According to Macedonian historians, most of its activists were ethnic Macedonians.

The House of Gjorgji Pulevski is a historical house in Galičnik that is listed as Cultural heritage of North Macedonia. It is the birth house of the Macedonian writer, lexicographer, historian, and military leader Gjorgji Pulevski.

Isaija Radev Mažovski was a Mijak painter and activist. Mažovski sought political solutions in the liberation of Ottoman Macedonia. A Slavophile, he travelled to Russia to establish contacts with prominent individuals there including the Russian tsar, hoping to gain support for Macedonian liberation.

Stefan Jakimov Dedov was a journalist, writer and early proponent of the Macedonian Slavs' ethnonational distinctiveness. He publicly expressed the idea of a Macedonian nation distinct from the Bulgarians, as well as a separate Macedonian language. He also self-identified occasionally as a Bulgarian.

Due to the lack of original protocol documentation, and the fact its early organic statutes were not dated, the first statute of the clandestine Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) is uncertain and is a subject to dispute among researchers. The dispute also includes its first name and ethnic character, as well as the authenticity, dating, validity, and authorship of its supposed first statute. Certain contradictions and inconsistencies exist in the testimonies of the founding and other early members of the Organization, which further complicates the solution of the problem. It is not yet clear whether the earliest statutory documents of the Organization have been discovered. Its earliest basic documents discovered for now, became known to the historical community during 1960s.

Trifon Kostadinov Grekov or Trifun Grekovski, also known as Trifun Greković, was a Macedonian physician, emigrant political activist during and after the First World War and Macedonian Partisan during the Second World War.

Božidar "Božo" Vidoeski was a Macedonian linguist and the founder of Macedonian dialectology.