| |

Chechnya | Georgia |

|---|---|

Relations between Georgia and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria began in 1991, when both countries declared independence from the Soviet Union. They continued to pursue relations until Chechnya was re-annexed by Russia in 2000.

| |

Chechnya | Georgia |

|---|---|

Relations between Georgia and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria began in 1991, when both countries declared independence from the Soviet Union. They continued to pursue relations until Chechnya was re-annexed by Russia in 2000.

Chechnya and Georgia declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Both nations aimed to gain international support against the Soviet Union and Russia.

During the spring of 1991, Dzhokhar Dudayev and Zviad Gamsakhurdia met in the Georgian town of Kazbegi. The meeting was arranged by Aslan Abashidze, a leader of Georgia's autonomous Adjarian republic. By that time, Dzokhar Dudayev had been chairman of oppositional All-National Congress of the Chechen People since November 1990, while Gamsakhurdia had been the chairman of Georgian parliament since November 1990 and President of Georgia since April 1991. Gamsakhurdia sought Dudayev's support against Russian-backed Ossetian separatist militants in Georgia's South Ossetian autonomy (Chechens' ethnic cousin Ingushs themselves having territorial dispute with Ossetians in East Prigorodny). Gamsakhurdia told Dudayev that Georgia had no problem to support Chechnya based on "mutual hostility to Russia and communism". Two leaders discussed establishing "Caucasian commonwealth of free and independent states". [1]

Dudayev enlisted Gamsakhurdia's support in the spring. Gamsakhurdia provided Dudayev with a geopolitical and trade "back door" leading through Georgia to Turkey and Black Sea. [1] Moreover, Dudayev received weapons from Gamsakhurdia through the Akhmeta Municipality of Georgia. [2]

In September–October 1991, Dudayev's supporters seized power in Chechnya in the Chechen Revolution. Dudayev was subsequently elected as Chechnya's President and in this new position, he proclaimed Chechnya's independence from Russia. The move was welcomed by Georgia's President Zviad Gamsakhurdia. Gamsakhurdia was one of the first to congratulate Dudayev with victory and attended his inauguration as president in Grozny. [3] While Chechnya did not receive backing from international community, it received support and attention from Georgia, which became its only gateway to the outside world that was not controlled by Moscow. Close ties between Gamsakhurdia and Dudayev led to Russian officials, including Alexander Rutskoy, accusing Georgia of "fomenting unrest in the [Chechen autonomous] republic". [4]

According to Stephen F. Jones, a historian and specialist on Russian and Eurasian studies, against the background of uneasy relations with both Russia and the West, Gamsakhurdia's administration saw Chechnya as a crucial regional ally. Gamsakhurdia and Dudayev promoted the concept of "Common Caucasian House", a regional alliance against foreign interference. Georgian-Chechen partnership was seen as pivotal to its success. [5]

In January 1992, Gamsakhurdia was overthrown in Georgia by the armed opposition and he had to flee the country. He was given asylum in Chechnya. Gamsakhurdia continued to fight for his power in Georgia, and Chechnya became base of his operations against new Georgian government of Eduard Shevardnadze. Meanwhile, Gamsakhurdia and Dudayev also deepened their cooperation and further promoted a Union of Caucasian States. In February 1992, they signed a joint communique, stating that stabilization in the Caucasus was impossible without cooperation. They also urged Russia to withdraw its troops from the region. [6] Gamsakhurdia and Dudayev organized "All-Caucasian Conference" which was attended by groups pushing for independence from Russia from all over the region. In March 1992, Gamsakhurdia's government in exile officially recognized Chechnya's independence and established diplomatic relations. Thus, it became the first government in the world to do so. [7] [8] However, Eduard Shevardnadze and the Georgia's ruling State Council in Tbilisi did not confirm this acknowledgment.

Due to Dudayev's ties with Gamsakhurdia, relations with the new Georgian government soared, and it closed its border to Chechnya, thus aggravating its international situation. [9] The relations were further complicated by the involvement of Chechen battalion led by Shamil Basayev in the War in Abkhazia on Russian-backed Abkhazian side against the Georgian government.

In September 1993, Gamsakhurdia flew from Chechnya to Georgia and led a rebellion to regain power. A brief civil war saw Gamsakhurdia being defeated by Shevardnadze with Russian military support, and in January 1994 Gamsakhurdia was announced dead. During the civil war, Shevardnadze made an accusation that Dudayev's troops were fighting on Gamsakhurdia's side, an allegation denied in Grozny. Chechen officials asked the Georgian government to allow Gamsakhurdia’s remains to be buried in his family's cemetery next to his home in Tbilisi or, in case of refusal, to transfer his body to be buried in Chechnya. [10] There were appeals to name a street in Grozny after Gamsakhurdia. [10] In February 1994, Gamsakhurdia's body was discovered in the western Georgia by a joint commission from Georgia and Chechnya, which led to the Georgian government confirming Gamsakhurdia's death. [11] On 17 February, Gamsakhurdia's remains were buried in Grozny. [12] [13] Dudayev provided state funeral and Orthodox Christian last rites to Gamsakhurdia. During his burial in Grozny in February 1994, Dudayev stated: "We are gathered here today to give back to the earth a brave son of the Caucasus, a man who believed in freedom." [14]

During the First Chechen War, Shevardnadze supported Russia's military campaign, in a hope that Russia would "come to its senses" and "understand its mistake" of supporting "aggressive separatism", thus it would help Georgia to regulate Abkhazia and South Ossetia conflicts. [15] Shevardnadze called First Chechen War a "boomerang" for Russia and stated that "everything that is happening in Chechnya began with Abkhazia".

Following the First Chechen War and Dudayev's death, there was an attempt to rebuild relations by the Georgian government of Eduard Shevardnadze and new Chechen President, Aslan Maskhadov. A series of meetings occurred in the spring of 1997, including one on 15 March 1997 in the Ingush capital of Nazran, between Chechen President Aslan Maskhadov, Ingush President Ruslan Aushev and Georgian defense minister Vardiko Nadibaidze, with Russia's prior approval. [16] In August 1997, Maskhadov visited Tbilisi and Akhmeta Municipality, where estimated 7,000 Chechens live. Maskhadov met Zurab Zhvania, chairman of Georgia's parliament. [17] Maskhadov and Shevardnadze reached an agreement on building a highway connecting Grozny and Tbilisi that would give Ichkeria an outlet to the sea. However, Georgia made it clear that it would not open an airspace to Chechnya. [18]

During his meeting with Georgian officials, Chechen President Aslan Maskhadov acknowledged that Chechen involvement in Abkhazia conflict was a mistake and apologized for it. He also expressed readiness to offer help to resolve the conflict through mediation. [19] Maskhadov called Chechen involvement in Abkhazia conflict "Dudayev's mistake" and made a commitment to severely punish any Chechen who would participate in actions against Georgia. [16] On another occasion, Maskhadov said: "Unfortunately, we were slow to understand that the Kremlin involved us in that [Abkhaz] conflict by telling us to help the Abkhaz as our Muslim brothers. That was a dirty policy directed not only against Georgia but, as it turned out, against us". [20]

Soon after these meetings in 1997, an Office of the Representative of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria was opened in Georgia. [17]

Despite these improvements, there were still limitations to Chechen-Georgian "strategic cooperation". Although Shevardnadze had begun to loosen his ties with Russia in 1996, Georgia sought to pursue cautious policy not to risk confrontation with Moscow. As such, Minister of State Nino Lekishvili stated that Georgia would pursue relations with Chechnya while guiding by the principle that the republic was part of Russian Federation. Georgia feared that Georgia's support for Ichkeria would lead Russia to use "instability on its border" as a pretext for exerting pressure on Tbilisi. [18]

Besides that, Chechen violent crime in Akhmeta also complicated relations. Over the years, Chechen armed groups engaged in kidnapping of Georgian citizens, and the Chechen community in Akhmeta engaged in the smuggling and sale of narcotics in Georgia. [18]

In September 1999, during the war in Dagestan, Shevardnadze and Georgian State Minister Vazha Lortkipanidze met Chechen Vice President Vakha Arsanov and announced mutual support. During the Second Chechen War, Georgia opened its border for Chechen refugees, while Russian President Vladimir Putin accused Georgia of harboring Chechen militants and becoming a "safe heaven" for "terrorists". Shevardnadze did not express support for Russian actions. [15] According to some reports, money supporting Chechen insurgents was channeled through Georgia. Russia insisted on using Georgian air space to launch operations against "Chechen terrorists" and it also wanted Georgia to allow Russian border guards to control the Georgian side of Chechen-Georgian border, but Shevardnadze refused Russian requests. This led to straining of Georgia–Russia relations. In November 2000, Russian President Vladimir Putin introduced a visa regime for Georgian citizens and a visa free regime for the residents of Georgia's breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia. This was despite the fact that citizens from other republics of Commonwealth of Independent States were not required visas to travel to Russia. Russia asserted that Georgia sheltered fighters from Chechnya and that visas were necessary to "guard against infiltration". [21] Gas supply from Russia was repeatedly cut off to Georgia in winter 2000, which was widely seen as a Russian response to growing Russia-Georgia tensions. [22]

Chechnya, officially the Chechen Republic, is a republic of Russia. It is situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, between the Caspian Sea and Black Sea. The republic forms a part of the North Caucasian Federal District, and shares land borders with the country of Georgia to its south; with the Russian republics of Dagestan, Ingushetia, and North Ossetia-Alania to its east, north, and west; and with Stavropol Krai to its northwest.

The First Chechen War, also referred to as the First Russo-Chechen War, was a struggle for independence waged by the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria against the Russian Federation from December 11th, 1994 to August 31st, 1996. This conflict was preceded by the battle of Grozny in November 1994, during which Russia covertly sought to overthrow the new Chechen government. Following the intense Battle of Grozny in 1994–1995, which concluded as a pyrrhic victory for the Russian federal forces, their subsequent efforts to establish control over the remaining lowlands and mountainous regions of Chechnya were met with fierce resistance from Chechen guerrillas who often conducted surprise raids.

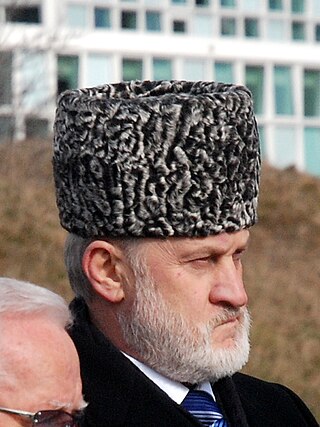

Akhmed Halidovich Zakayev is a Chechen statesman, political and military figure of the unrecognised Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (ChRI). Having previously been a Deputy Prime Minister, he now serves as Prime Minister of the ChRI government-in-exile. He was also the Foreign Minister of the Ichkerian government, appointed by Aslan Maskhadov shortly after his 1997 election, and again in 2006 by Abdul Halim Sadulayev. An active participant in the Russian-Chechen wars, Zakayev took part in the battles for Grozny and the defense of Goyskoye, along with other military operations, as well as in high-level negotiations with the Russian side.

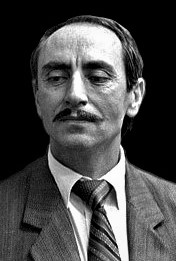

Zviad Konstantines dze Gamsakhurdia was a Georgian politician, human rights activist, dissident, professor of English language studies and American literature at Tbilisi State University, and writer who became the first democratically elected President of Georgia in May 1991.

Aslan (Khalid) Aliyevich Maskhadov was a Soviet and Chechen politician and military commander who served as the third president of the unrecognized Chechen Republic of Ichkeria.

The history of Chechnya may refer to the history of the Chechens, of their land Chechnya, or of the land of Ichkeria.

Zelimkhan Abdulmuslimovich Yandarbiyev was a writer and politician from Chechnya, who served as acting president of the breakaway Chechen Republic of Ichkeria between 1996 and 1997. Yandarbiyev was deemed by UN a suspected associate of Al-Qaeda extremist group, and is the first of Chechen leader to be named part of Al-Qaeda terrorist network. In 2004, Yandarbiyev was assassinated while in exile in Qatar.

Dzhokhar Musayevich Dudayev was a Chechen politician, statesman and military leader of the 1990s Chechen Independence movement from Russia. He served as the first president of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, from 1991 until his assassination in 1996. Previously he had been a Major General of Aviation in the Soviet Armed Forces.

Said-Magomed Shamaevich Kakiyev is a colonel in the Russian Army, who was the leader of the GRU Spetsnaz Special Battalion Zapad ("West"), a Chechen military force, from 2003 to 2007. Inside Chechnya his men were sometimes referred to as the Kakievtsy. Unlike the other Chechen pro-Moscow forces in Chechnya, Kakiyev and his men are not former rebels and during the First Chechen War were some of the few Chechen militants who fought on the Russian side.

Sultan Geliskhanov is a former head of the state security service in the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and a former field commander in the Chechen resistance against Russia.

Ruslan (Khamzat) Germanovich Gelayev was a prominent commander in the Chechen resistance movement against Russia, in which he played a significant, yet controversial, military and political role in the 1990s and early 2000s. Gelayev was commonly viewed as an abrek and a well-respected, ruthless fighter. His operations spread well beyond the borders of Chechnya and even outside the Russian Federation and into Georgia. He was killed while leading a raid into the Russian Republic of Dagestan in 2004.

The Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, known simply as Ichkeria, and also known as Chechnya, was a de facto state that controlled most of the former Checheno-Ingush ASSR.

Movladi Saidarbievich Udugov is the former First Deputy Prime Minister of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (ChRI). As a Chechen propaganda chief, he was credited for the Chechens' victory on the information front during the First Chechen War.

Vakha Arsanov was a vice president in the Aslan Maskhadov government of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria.

The Russia–Chechnya Peace Treaty of 1997, also known as the Moscow Peace Treaty, was a formal peace treaty "on peace and the principles of Russian–Chechen relations" following the First Chechen War of 1994–1996. It was signed by the president of Russia Boris Yeltsin and the newly elected president of Chechnya Aslan Maskhadov on 12 May 1997, in the Moscow Kremlin.

Relations and contacts between Estonia and Ichkeria have historically been, and are, very friendly due to the two peoples having similar experiences and perceiving a common foe, be it Russian Empire, the Soviet Union or the modern Russian Federation. The Estonian people and the Chechen people, in addition to actively helping each others' covert activities against Moscow, have at various times borrowed tactics and ideologies from each other.

The Province of Nokhchicho was the Chechen-based wing of the Caucasus Emirate organisation. It was created in 2007 as one of the Emirate's six vilayats, replacing the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria.

Isa Akhyadovich Munayev was a Chechen rebel and military commander who fought for the independence of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria from Russia until he was forced into exile in Europe around 2004. He was killed in action while leading a Chechen volunteer unit on the Ukrainian side during the war in Donbas in 2015.

Pan-Caucasianism is a political current supporting the cooperation and integration of some or all peoples of the Caucasus. Pan-Caucasianism has been hindered by the ethnic, religious and cultural diversity of the Caucasus, and frequent regional conflicts. Historically popular during the Russian Civil War, pan-Caucasianism has formed a part of the foreign policy of Georgia and Chechen militants since the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

By late 1996, the stance of the Chechen leadership toward Georgia under Shevardnadze had completely changed. The then Chechen prime minister (and former military chief-of-staff) Aslan Maskhadov and then acting president Zelimkhan Yandarbiev told Georgian journalists that they were seeking a meeting "any time, any place" to overcome differences with Georgia and to become "real allies" and "strategic partners" with them. The two Chechen leaders (unconvincingly) blamed Moscow for having misled the Chechens into supporting Abkhaziya's secessionist war against Georgia. "Unfortunately," Maskhadov confided, "we were slow to understand that the Kremlin involved us in that conflict by telling us to help the Abkhaz as our Muslim brothers. That was a dirty policy directed not only against Georgia but, as it turned out, against us." Efforts then began to hold a meeting between Yandarbiev and Shevardnadze. The latter cautiously welcomed the overtures from the Chechens while signaling that he would not be drawn into an anti-Russian front.