The yellow-billed cuckoo is a member of the cuckoo family. Common folk names for this bird in the southern United States are rain crow and storm crow. These likely refer to the bird's habit of calling on hot days, often presaging rain or thunderstorms. The genus name is from the Ancient Greek kokkuzo, which means to call like a common cuckoo, and americanus means "of America".

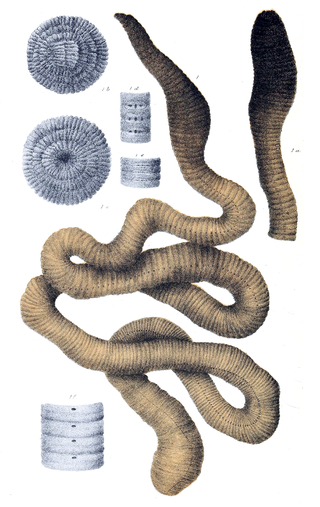

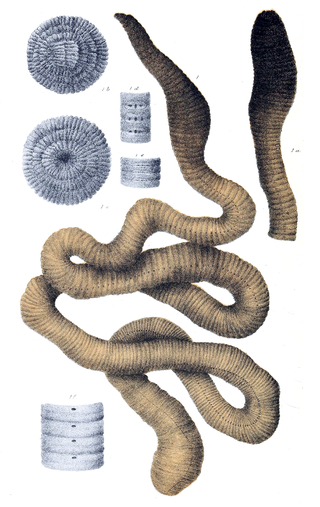

Oligochaeta is a subclass of soft-bodied animals in the phylum Annelida, which is made up of many types of aquatic and terrestrial worms, including all of the various earthworms. Specifically, oligochaetes comprise the terrestrial megadrile earthworms, and freshwater or semiterrestrial microdrile forms, including the tubificids, pot worms and ice worms (Enchytraeidae), blackworms (Lumbriculidae) and several interstitial marine worms.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is the primary law in the United States for protecting and conserving imperiled species. Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation", the ESA was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973. The Supreme Court of the United States described it as "the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species enacted by any nation". The purposes of the ESA are two-fold: to prevent extinction and to recover species to the point where the law's protections are not needed. It therefore "protect[s] species and the ecosystems upon which they depend" through different mechanisms. For example, section 4 requires the agencies overseeing the Act to designate imperiled species as threatened or endangered. Section 9 prohibits unlawful 'take,' of such species, which means to "harass, harm, hunt..." Section 7 directs federal agencies to use their authorities to help conserve listed species. The Act also serves as the enacting legislation to carry out the provisions outlined in The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

The Palouse is a distinct geographic region of the northwestern United States, encompassing parts of north central Idaho, southeastern Washington, and, by some definitions, parts of northeast Oregon. It is a major agricultural area, primarily producing wheat and legumes. Situated about 160 miles (260 km) north of the Oregon Trail, the region experienced rapid growth in the late 19th century.

The northern Idaho ground squirrel is a species of the largest genus of ground squirrels. This species and the Southern Idaho ground squirrel were previously considered conspecific, together called the Idaho ground squirrel.

In paleontology, a Lazarus taxon is a taxon that disappears for one or more periods from the fossil record, only to appear again later. Likewise in conservation biology and ecology, it can refer to species or populations that were thought to be extinct, and are rediscovered. The term Lazarus taxon was coined by Karl W. Flessa and David Jablonski in 1983 and was then expanded by Jablonski in 1986. Paul Wignall and Michael Benton defined Lazarus taxa as, "At times of biotic crisis many taxa go extinct, but others only temporarily disappeared from the fossil record, often for intervals measured in millions of years, before reappearing unchanged". Earlier work also supports the concept though without using the name Lazarus taxon, like work by Christopher R. C. Paul.

The giant Gippsland earthworm, is one of Australia's 1,000 native earthworm species.

The giant armadillo, colloquially tatu-canastra, tatou, ocarro or tatú carreta, is the largest living species of armadillo. It lives in South America, ranging throughout as far south as northern Argentina. This species is considered vulnerable to extinction.

Nicrophorus americanus, also known as the American burying beetle or giant carrion beetle, is a critically endangered species of beetle endemic to North America. It belongs to the order Coleoptera and the family Silphidae. The carrion beetle in North America is carnivorous, feeds on carrion and requires carrion to breed. It is also a member of one of the few genera of beetle to exhibit parental care. The decline of the American burying beetle has been attributed to habitat loss, alteration, and degradation, and they now occur in less than 10% of their historic range.

The pygmy rabbit is a rabbit species native to the United States. It is also the only native rabbit species in North America to dig its own burrow. The pygmy rabbit differs significantly from species within either the Lepus (hare) or Sylvilagus (cottontail) genera and is generally considered to be within the monotypic genus Brachylagus. One isolated population, the Columbia Basin pygmy rabbit, is listed as an endangered species by the U.S. Federal government, though the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the species as lower risk.

Zaglossus attenboroughi, also known as Attenborough's long-beaked echidna or locally as Payangko, is one of three species from the genus Zaglossus that inhabits the island of New Guinea. It lives in the Cyclops Mountains, which are near the cities of Sentani and Jayapura in the Indonesian province of Papua. It is named in honour of naturalist Sir David Attenborough.

The Mazama pocket gopher is a smooth-toothed pocket gopher restricted to the Pacific Northwest. The herbivorous species ranges from coastal Washington, through Oregon, and into north-central California. Four subspecies of the Mazama Pocket Gopher are classified as threatened under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, including T. m. pugetensis, T. m. tumuli , T. m. glacialis, and T. m. yelmensis. The Mazama Pocket Gopher is one of the smallest of 35 species in the pocket gopher family.

The Utah prairie dog is the smallest species of prairie dog endemic to the south-central steppes of the American state of Utah.

Amaranthus brownii was an annual herb in the family Amaranthaceae. The plant was found only on the small island of Nihoa in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, growing on rocky outcrops at altitudes of 120–215 m (394–705 ft). It was one of nine species of Amaranthus in the Hawaiian Islands, as well as the only endemic Hawaiian species of the genus. It is now considered extinct.

The Liberian mongoose is a mongoose species native to Liberia and Ivory Coast. It is the only member of the genus Liberiictis. Phylogenetic analysis shows it is closely related to other small, social mongooses and that the banded mongoose is its closest relative.

Julie A. MacDonald is a former deputy assistant secretary for Fish and Wildlife and Parks at the United States Department of the Interior. MacDonald was appointed by former Secretary of the Interior Gale Norton on 3 May 2004 and resigned on 1 May 2007 after an internal investigation found that she had "injected herself personally and profoundly in a number of Endangered Species Act decisions", a violation of the Code of Federal Regulations under Use of Nonpublic Information and Basic Obligation of Public Service, Appearance of Preferential Treatment.

The giant golden mole is a small mammal found in Africa. At 23 centimetres (9.1 in) in length, it is the largest of the golden mole species. This mole has dark, glossy brown fur; the name golden comes from the Greek word for green-gold, the family Chrysochloridae name.

The rough-haired golden mole is a species of mammal that live mostly below ground. They have shiny coats of dense fur and a streamlined, formless appearance. They have no visible eyes or ears; in fact, they are blind - the small eyes are covered with hairy skin. The ears are small and are hidden in the animal's fur.

The Oregon giant earthworm is one of the largest earthworms found in North America, growing to more than three feet in length. First described in 1937, the species is not common. Since its discovery, specimens have been documented in only fifteen locations within Oregon's Willamette Valley.

An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for the largest members of the class Oligochaeta. In classical systems, they were in the order of Opisthopora since the male pores opened posterior to the female pores, although the internal male segments are anterior to the female. Theoretical cladistic studies have placed them in the suborder Lumbricina of the order Haplotaxida, but this may change. Other slang names for earthworms include "dew-worm", "rainworm", "nightcrawler", and "angleworm". Larger terrestrial earthworms are also called megadriles as opposed to the microdriles in the semiaquatic families Tubificidae, Lumbricidae and Enchytraeidae. The megadriles are characterized by a distinct clitellum and a vascular system with true capillaries.