Zora Neale Hurston was an American author, anthropologist, and filmmaker. She portrayed racial struggles in the early-1900s American South and published research on hoodoo. The most popular of her four novels is Their Eyes Were Watching God, published in 1937. She also wrote more than 50 short stories, plays, and essays.

Apopka is a city in Orange County, Florida. The city's population was 55,000 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Orlando–Kissimmee–Sanford Metropolitan Statistical Area. Apopka comes from Seminole word Ahapopka for "Potato eating place".

Eatonville is a town in Orange County, Florida, United States, six miles north of Orlando. It is part of Greater Orlando. Incorporated on August 15, 1887, it was one of the first self-governing all-black municipalities in the United States. The Eatonville Historic District and Moseley House Museum are in Eatonville. Author Zora Neale Hurston grew up in Eatonville and the area features in many of her stories.

Sanford is a city in the U.S. state of Florida and the county seat of Seminole County. It is located in Central Florida and its population was 61,051 as of the 2020 census.

Their Eyes Were Watching God is a 1937 novel by American writer Zora Neale Hurston. It is considered a classic of the Harlem Renaissance, and Hurston's best known work. The novel explores protagonist Janie Crawford's "ripening from a vibrant, but voiceless, teenage girl into a woman with her finger on the trigger of her own destiny".

The Orlando metropolitan area, commonly referred to as Greater Orlando, Metro Orlando, Central Florida as well as for U.S. Census purposes as the Orlando–Kissimmee–Sanford, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area, is a metropolitan area in the central region of the U.S. state of Florida. Its principal cities are Orlando, Kissimmee and Sanford. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget defines it as consisting of the counties of Lake, Orange, Osceola, and Seminole.

Eau Gallie is a section of the city of Melbourne, Florida, located on the city's northern side. It was an independent city in Brevard County from 1860 until 1969.

The Zora Neale Hurston House is a historic house at 1734 Avenue L in Fort Pierce, Florida. Built in 1957, it was the home of author Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960) from then until her death. On December 4, 1991, it was designated as a U.S. National Historic Landmark.

Anas "Andy" Shallal is an Iraqi-American artist, activist, philanthropist and entrepreneur. He is best known as the founder and CEO of the Washington, D.C., area, restaurant, bookstore, and performance venue Busboys and Poets. He is also known for his opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He was a candidate for the city's mayoral election in 2014.

The Ocoee massacre was a mass racial violence event that saw a white mob attack numerous African-American residents in the northern parts of Ocoee, Florida, a town located in Orange County near Orlando. The massacre took place on November 2, 1920, the day of the U.S. presidential election.

Forrest Lake (1868-1939) was a prominent politician, banker, real estate investor, a mayor of Sanford, Florida and a member of the Florida House of Representatives. Lake had an instrumental role in the formation of Seminole County. In 1928, Lake was convicted of embezzlement and served 3 years of a 14-year sentence.

The Zora Neale Hurston National Museum of Fine Arts, also known as The Hurston, is an art museum in Eatonville, Florida. The Hurston is named after Zora Neale Hurston, an African-American writer, folklorist, and anthropologist who moved to Eatonville at a young age and whose father became mayor of Eatonville in 1897. The museum's exhibits are centered on individuals of African descent, from the diaspora and the United States. The Hurston features exhibitions quarterly to highlight emerging artists.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Orlando, Florida, United States.

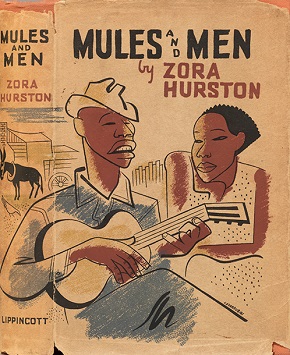

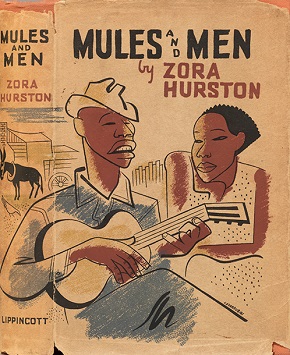

Mules and Men is a 1935 autoethnographical collection of African-American folklore collected and written by anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston. The book explores stories she collected in two trips: one in Eatonville and Polk County, Florida, and one in New Orleans. Hurston's decision to focus her research on Florida came from a desire to record the cross-section of black traditions in the state. In her introduction to Mules and Men, she wrote, "Florida is a place that draws people—white people from all over the world, and Negroes from every Southern state surely and some from the North and West". Hurston documented 70 folktales during the Florida trip, while the New Orleans trip yielded a number of stories about Marie Laveau, voodoo and Hoodoo traditions. Many of the folktales are told in vernacular; recording the dialect and diction of the Black communities Hurston studied.

Joseph Nathaniel Crooms, also known as J. N. Crooms, was an African American principal and educator in Florida. He established two schools for African American students in Seminole County, the first being Hopper Academy and the second being Crooms Academy in Goldsboro, Florida, in 1926. Crooms Academy was the first four-year high school for African Americans in Seminole County, Florida.

"How It Feels To Be Colored Me" (1928) is an essay by Zora Neale Hurston published in World Tomorrow as a "white journal sympathetic to Harlem Renaissance writers", illustrating her circumstance as an African-American woman in the early 20th century in America. Most of Hurston's work involved her "Negro" characterization that were so true to reality, that she was known as an excellent anthropologist.

Moseley House Museum is a house museum located in Eatonville, Florida. The house is the second oldest structure in the town, constructed in 1888. The house was owned by Jim and Matilda Clark Moseley, Matilda was the niece of Eatonville's founder and first mayor. Author Zora Neale Hurston was a friend of Matilda and often visited the house. The house was restored and opened as a museum in 2000. It currently exhibits early Eatonville memorabilia.

Ann Graves Tanksley is an American artist. Her mediums are representational oils, watercolor and printmaking. One of her most noteworthy bodies of work is a collection based on the writings of African-American novelist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston. The Hurston exhibition is a two hundred plus piece collection of monotypes and paintings. It toured the United States on and off from 1991 through 2010.

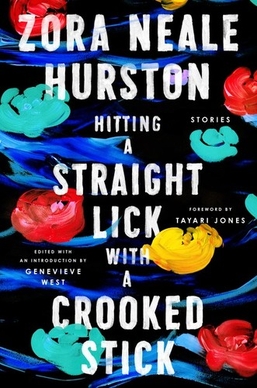

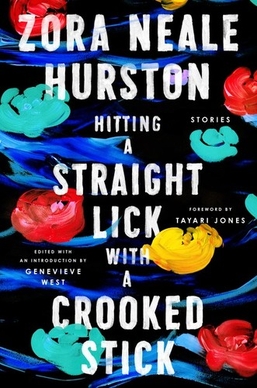

Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick is a compilation of recovered short stories written by Zora Neale Hurston. It was published in 2020 by Amistad: An Imprint of HarperCollins publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-291579-5