Cartography is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality can be modeled in ways that communicate spatial information effectively.

The Bodleian Library is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in Britain after the British Library. Under the Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003, it is one of six legal deposit libraries for works published in the United Kingdom, and under Irish law it is entitled to request a copy of each book published in the Republic of Ireland. Known to Oxford scholars as "Bodley" or "the Bod", it operates principally as a reference library and, in general, documents may not be removed from the reading rooms.

Richard Gough was a prominent and influential English antiquarian. He served as director of the Society of Antiquaries of London from 1771 to 1791; published a major work on English church monuments; and translated and edited a new edition of William Camden's Britannia.

The history of geography includes many histories of geography which have differed over time and between different cultural and political groups. In more recent developments, geography has become a distinct academic discipline. 'Geography' derives from the Greek γεωγραφία – geographia, literally "Earth-writing", that is, description or writing about the Earth. The first person to use the word geography was Eratosthenes. However, there is evidence for recognizable practices of geography, such as cartography, prior to the use of the term.

The Hereford Mappa Mundi is the largest medieval map still known to exist, depicting the known world. It is a religious rather than literal depiction, featuring heaven, hell and the path to salvation. The map is drawn in a form deriving from the T and O pattern, dating from c. 1300. It is displayed at Hereford Cathedral in Hereford, England. The map was created with the intent of its being appreciated as an intricate work of art rather than as a navigational tool. Sources for the information presented on the map include the Alexander tradition, medieval bestiaries and Monstrous races tradition, as well as the Bible.

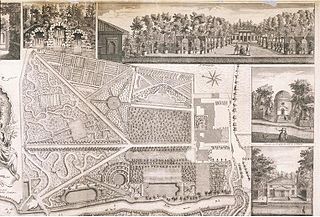

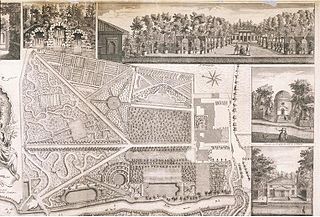

John Rocque was a French-born British surveyor and cartographer, best known for his detailed map of London published in 1746.

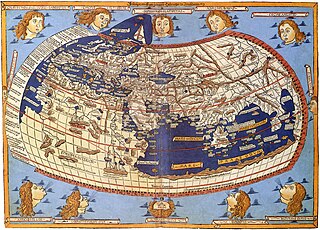

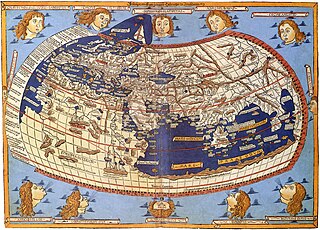

The earliest known world maps date to classical antiquity, the oldest examples of the 6th to 5th centuries BCE still based on the flat Earth paradigm. World maps assuming a spherical Earth first appear in the Hellenistic period. The developments of Greek geography during this time, notably by Eratosthenes and Posidonius culminated in the Roman era, with Ptolemy's world map, which would remain authoritative throughout the Middle Ages. Since Ptolemy, knowledge of the approximate size of the Earth allowed cartographers to estimate the extent of their geographical knowledge, and to indicate parts of the planet known to exist but not yet explored as terra incognita.

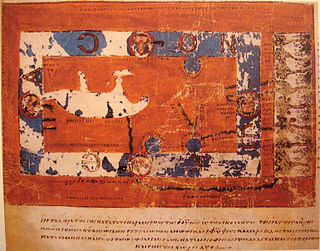

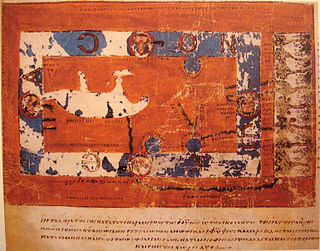

The Christian Topography is a 6th-century work, one of the earliest essays in scientific geography written by a Christian author. It originally consisted of five books written by Cosmas Indicopleustes and expanded to ten and eventually to twelve books at around 550 AD.

A road map, route map, or street map is a map that primarily displays roads and transport links rather than natural geographical information. It is a type of navigational map that commonly includes political boundaries and labels, making it also a type of political map. In addition to roads and boundaries, road maps often include points of interest, such as prominent businesses or buildings, tourism sites, parks and recreational facilities, hotels and restaurants, as well as airports and train stations. A road map may also document non-automotive transit routes, although often these are found only on transit maps.

"Majorcan cartographic school" is the term coined by historians to refer to the collection of predominantly Jewish cartographers, cosmographers and navigational instrument-makers and some Christian associates that flourished in Majorca in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries until the expulsion of the Jews. The label is usually inclusive of those who worked in Catalonia. The Majorcan school is frequently contrasted with the contemporary Italian cartography school.

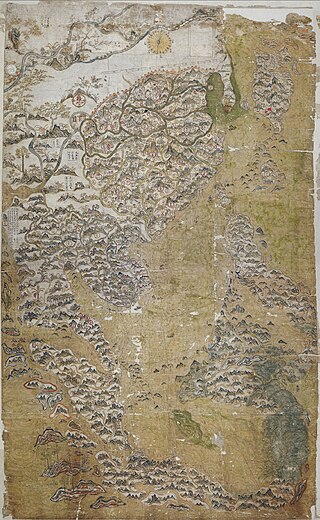

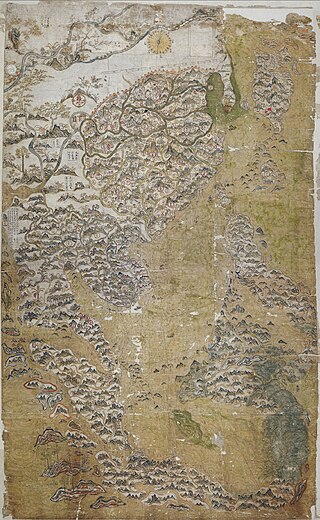

The Selden Map of China is an early 17th century map of East Asia formerly owned by the legal scholar and maritime theorist John Selden. It shows a system of navigational routes emanating from a point near the cities of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou in Fujian Province, from which a principal route goes northeast towards Nagasaki and southwest towards Hoi An, then Champa, and then on to Pahang, and then with another route heading past Penghu towards a point northwest by Manila.

Sheldon tapestries were produced at Britain's first large tapestry works in Barcheston, Warwickshire, England, established by the Sheldon family. A group of 121 tapestries dateable to the late 16th century were produced. Much the most famous are four tapestry maps illustrating the counties of Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Oxfordshire and Warwickshire, with most other tapestries being small furnishing items, such as cushion covers. The tapestries are included in three major collections: the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Burrell Collection, Glasgow, Scotland. Pieces were first attributed in the 1920s to looms at Barcheston, Warwickshire by a Worcestershire antiquary, John Humphreys, without clear criteria; on a different, but still uncertain basis, others were so classified a few years later. No documentary evidence was then, or is now, associated with any tapestry, so no origin for any piece is definitely established.

The Island of the Jewel or Island of Sapphires was a semi-legendary island in medieval Arabic cartography, said to lie in the Sea of Darkness near the equator, forming the eastern limit of the inhabited world. The island does not appear in any surviving manuscript of Ptolemy's Geography nor other Greek geographers. Instead, it is first attested in the Ptolemaic-influenced Book of the Description of the Earth compiled by al-Khwārizmī around 833. Ptolemy's map ended at 180° E. of the Fortunate Isles without being able to explain what might lay on the imagined eastern shore of the Indian Ocean or beyond the lands of Sinae and Serica in Asia. Roman missions subsequently reached the Han court via Longbian (Hanoi) and Chinese Muslims traditionally credit the founding of their community to the Companion Saʿd ibn Abi Waqqas as early as the 7th century. Muslim merchants such as Soleiman established sizable expatriate communities; a large-scale massacre of Arabs and Persians is recorded at Yangzhou in 760. These connections showed al-Khwārizmī and other Islamic geographers that the Indian Ocean was not closed as Hipparchus and Ptolemy had held but opened either narrowly or broadly.

De laude Cestrie, also known as Liber Luciani de laude Cestrie, is a medieval English manuscript in Latin by Lucian of Chester, probably a monk at the Benedictine Abbey of St Werburgh in Chester. Believed to date from the end of the 12th century, it has been described as "the oldest extant piece of Cheshire writing," and, with its first-hand description of the medieval town of Chester, is one of the earliest examples of prose writing about an English urban centre. It is also notable for the earliest extended description of Chester's county palatine status, which Lucian writes "gives heed ... more to the sword of its prince than to the crown of the king." The original manuscript is held by the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Excerpts have been published in 1600, 1912 and 2008.

Elizabeth Solopova is a Russian-British philologist and medievalist undertaking research at New College, Oxford. She is known outside academic circles for her work on J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings.

Jerry Brotton is a British historian. He is Professor of Renaissance Studies at Queen Mary University of London, a television and radio presenter and a curator.

Emilie Savage-Smith is an American-British historian of science known for her work on science in the medieval Islamic world and medicine in the medieval Islamic world.

The Book of Curiosities is an anonymous 11th-century Arabic cosmography from Fatimid Egypt containing a series of early illustrated maps of the world and celestial diagrams of the universe and sky. TheBook of Curiosities contains 17 maps in total, 14 of which are extremely rare not only in Islamic cartography but also in greater medieval map history. The cosmography includes the earliest recorded map of Sicily as well as a rectangular world map, considered the earliest surviving map with a graphic scale. The autograph manuscript has not survived, but the Bodleian Library of Oxford University acquired one of the only known copies of the manuscript in 2002, making its contents widely accessible today due to its digitization. Based on the production processes and physical materials of the copy, such as paper and pigment, scholars date the production of this copy to the early 13th century.

Evelyn Edson is an author, medievalist, and professor emerita of history. She is known for her three books on the history of cartography.

Keith Lilley is Professor at Queen's University Belfast, known as a historical geographer and urban historian.