Related Research Articles

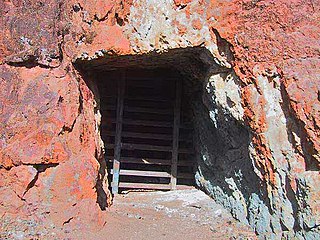

An adit or stulm is a horizontal or nearly horizontal passage to an underground mine. Miners can use adits for access, drainage, ventilation, and extracting minerals at the lowest convenient level. Adits are also used to explore for mineral veins. Although most strongly associated with mining, the term adit is sometimes also used in the context of underground excavation for non-mining purposes; for example, to refer to smaller underground passageways excavated for underground metro systems, to provide pedestrian access to stations, and for access required during construction.

Totley Tunnel is a 6,230-yard tunnel under Totley Moor, on the Hope Valley line between Totley on the outskirts of Sheffield and Grindleford in Derbyshire, England.

Aspull is a village in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, in Greater Manchester, England. Historically in Lancashire, Aspull, along with Haigh, is surrounded by greenbelt and agricultural land, separated from Westhoughton, on its southeast side, by a brook running through Borsdane Wood. The ground rises from south to north, reaching 400 feet (122 m), and has views towards Winter Hill and the West Pennine Moors. It has a population of 4,977.

Haigh is a village and civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, Greater Manchester, England. Historically part of Lancashire, it is located next to the village of Aspull. The western boundary is the River Douglas, which separates the township from Wigan. To the north, a small brook running into the Douglas divides it from Blackrod. At the 2001 census it had a population of 594.

Clifton Hall Colliery was one of two coal mines in Clifton on the Manchester Coalfield, historically in Lancashire which was incorporated into the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England in 1974. Clifton Hall was notorious for an explosion in 1885 which killed around 178 men and boys.

Wet Earth Colliery was a coal mine located on the Manchester Coalfield, in Clifton, Greater Manchester. The colliery site is now the location of Clifton Country Park. The colliery has a unique place in British coal mining history; apart from being one of the earliest pits in the country, it is the place where engineer James Brindley made water run uphill.

The Anson Engine Museum is situated on the site of the old Anson colliery in Poynton, Cheshire, England. It is the work of Les Cawley and Geoff Challinor who began collecting and showing stationary engines for a hobby. The museum now has one of the largest collections of engines in Europe. The museum site also includes a working blacksmith's smithy and carpentry shop and a café.

Chatterley Whitfield Colliery is a disused coal mine on the outskirts of Chell, Staffordshire in Stoke on Trent, England. It was the largest mine working the North Staffordshire Coalfield and was the first colliery in the UK to produce one million tons of saleable coal in a year.

The South Waratah Colliery was a coal mine located at Charlestown, in New South Wales Australia.

The Lancashire Coalfield in North West England was an important British coalfield. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period over 300 million years ago.

The Ingleton Coalfield is in North Yorkshire, close to its border with Lancashire in north-west England. Isolated from other coal-producing areas, it is one of the smallest coalfields in Great Britain.

Fletcher, Burrows and Company was a coal mining company that owned collieries and cotton mills in Atherton, Greater Manchester, England. Gibfield, Howe Bridge and Chanters collieries exploited the coal mines (seams) of the middle coal measures in the Manchester Coalfield. The Fletchers built company housing at Hindsford and a model village at Howe Bridge which included pithead baths and a social club for its workers. The company became part of Manchester Collieries in 1929. The collieries were nationalised in 1947 becoming part of the National Coal Board.

Bickershaw Colliery was a coal mine, located on Plank Lane in Leigh, then within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire, England.

Haigh Hall is a historic country house in Haigh, Wigan, Greater Manchester, England. Built between 1827 and 1840 for James Lindsay, 7th Earl of Balcarres, it replaced an ancient manor house and was a Lindsay family home until 1947, when it was sold to Wigan Corporation. The hall is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II* listed building and is owned by Wigan Council.

The Wigan Coal and Iron Company was formed when collieries on the Lancashire Coalfield owned by John Lancaster were acquired by Lord Lindsay, the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres, owner of the Haigh Colliery in 1865. The company owned collieries in Haigh, Aspull, Standish, Westhoughton, Blackrod, Westleigh and St Helens and large furnaces and iron-works near Wigan and the Manton Colliery in Nottinghamshire.

Parsonage Colliery was a coal mine operating on the Lancashire Coalfield in Leigh, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England. The colliery, close to the centre of Leigh and the Bolton and Leigh Railway was sunk between 1913 and 1920 by the Wigan Coal and Iron Company and the first coal was wound to the surface in 1921. For many years its shafts to the Arley mine were the deepest in the country. The pit was close to the town centre and large pillars of coal were left under the parish church and the town's large cotton mills.

Sir Roger Bradshaigh, 1st Baronet was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1660 to 1679.

This is a partial glossary of coal mining terminology commonly used in the coalfields of the United Kingdom. Some words were in use throughout the coalfields, some are historic and some are local to the different British coalfields.

Hapton Valley Colliery was a coal mine on the edge of Hapton near Burnley in Lancashire, England. Its first shafts were sunk in the early 1850s and it had a life of almost 130 years, surviving to be the last deep mine operating on the Burnley Coalfield.

References

- ↑ Anderson & France 1994, p. 16

- ↑ Davies 2010, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Great Haigh Sough, Wigan Archaeological Society, retrieved 2 February 2011

- ↑ Hatcher 1993, p. 215

- 1 2 Challinor 1972, p. 12

- ↑ Anderson & France 1994, p. 18

- 1 2 Anderson & France 1994, p. 9

- ↑ Davies 2010, p. 20

- ↑ Anderson & France 1994, p. 29

- 1 2 Anderson & France 1994, p. 31

- ↑ Ashmore 1982, p. 95

- ↑ Hatcher 1993 , p. 289

- ↑ Anderson & France 1994, p. 33

- ↑ Haigh Sough mine drainage portal, Pastscape.org.uk, retrieved 2 July 2011

- ↑ Anderson & France 1994, p. 14

- ↑ Anderson & France 1994, p. 10

- ↑ Case Study Aspull Sough Minewater Treatment Scheme, archived from the original on 12 September 2010, retrieved 3 April 2014

Bibliography

- Anderson, Donald; France, A.A. (1994), Wigan Coal and Iron, Smiths Books (Wigan), ISBN 0-9510680-7-5

- Ashmore, Owen (1982), The Industrial archaeology of North-west England, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-0820-4

- Challinor, Raymond (1972), The Lancashire and Cheshire Miners, Frank Graham, ISBN 0-902833-54-5

- Davies, Alan (2010), Coal Mining in Lancashire & Cheshire, Amberley, ISBN 978-1-84868-488-1

- Hatcher, John (1993), The history of the British coal industry, Volume I Before 1700, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-828282-2