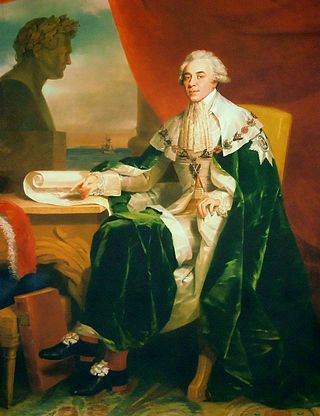

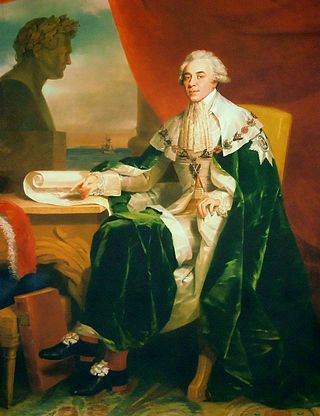

Francis II and I was the last Holy Roman Emperor as Francis II from 1792 to 1806, and the first Emperor of Austria as Francis I from 1804 to 1835. He was also King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia, and served as the first president of the German Confederation following its establishment in 1815.

The Holy Roman Empire, headed by the Holy Roman Emperor, developed in Central Europe in the Early Middle Ages and lasted for almost a thousand years until its dissolution in 1806.

The Peace of Westphalia is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy Roman Empire, closing a calamitous period of European history that killed approximately eight million people. Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III, the kingdoms of France and Sweden, and their respective allies among the princes of the Holy Roman Empire, participated in the treaties.

The Thirty Years' War, from 1618 to 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from the effects of battle, famine, or disease, while parts of Germany reported population declines of over 50%. Related conflicts include the Eighty Years' War, the War of the Mantuan Succession, the Franco-Spanish War, the Torstenson War, the Dutch-Portuguese War, and the Portuguese Restoration War.

The Treaty of Lunéville was signed in the Treaty House of Lunéville on 9 February 1801. The signatory parties were the French Republic and Emperor Francis II, who signed on his own behalf as ruler of the hereditary domains of the House of Austria and on behalf of the Holy Roman Empire. The signatories were Joseph Bonaparte and Count Ludwig von Cobenzl, the Austrian foreign minister. The treaty formally ended Austrian and Imperial participation in the War of the Second Coalition and the French Revolutionary Wars, as well as the Imperial Kingdom of Italy.

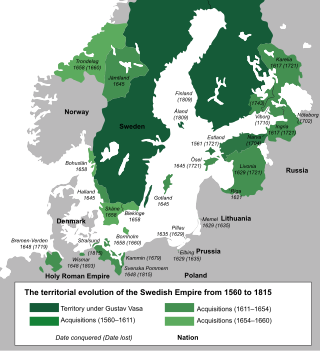

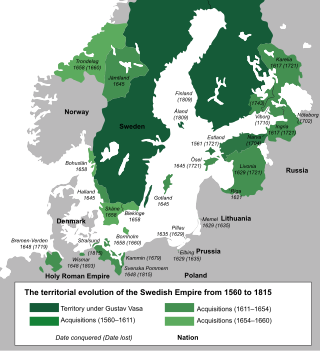

The Dominions of Sweden or Svenska besittningar were territories that historically came under control of the Swedish Crown, but never became fully integrated with Sweden. This generally meant that they were ruled by Governors-General under the Swedish monarch, but within certain limits retained their own established political systems, essentially their diets. Finland was not a dominion, but a land of Sweden. The dominions had no representation in the Swedish Riksdag as stipulated by the 1634 Instrument of Government paragraph 46: "No one, who is not living inside the separate and old borders of Sweden and Finland, have anything to say at Riksdags and other meetings..."

The Kingdom of Prussia constituted the German state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. It was the driving force behind the unification of Germany in 1866 and was the leading state of the German Empire until its dissolution in 1918. Although it took its name from the region called Prussia, it was based in the Margraviate of Brandenburg. Its capital was Berlin.

Count Nikolai Petrovich Rumyantsev, born in Saint Petersburg, was Russia's Foreign Minister and Chancellor of the Russian Empire in the run-up to Napoleon's invasion of Russia (1808–12). He was the son of Field Marshal Pyotr Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky from the Rumyantsev comital family.

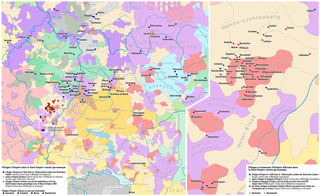

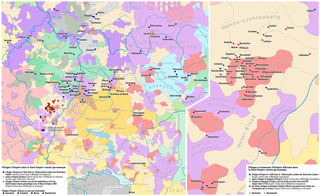

German mediatisation was the major redistribution and reshaping of territorial holdings that took place between 1802 and 1814 in Germany by means of the subsumption and secularisation of a large number of Imperial Estates, prefiguring, precipitating, and continuing after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. Most ecclesiastical principalities, free imperial cities, secular principalities, and other minor self-ruling entities of the Holy Roman Empire lost their independent status and were absorbed by the remaining states. By the end of the mediatisation process, the number of German states had been reduced from almost 300 to 39.

The Treaty of Teschen was signed on 13 May 1779 in Teschen, then in Austrian Silesia, between the Austrian Habsburg monarchy and the Kingdom of Prussia, which officially ended the War of the Bavarian Succession.

The Franco-Spanish War was fought from 1635 to 1659 between France and Spain, each supported by various allies at different points. The first phase, beginning in May 1635 and ending with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, is considered a related conflict of the Thirty Years' War. The second phase continued until 1659, when France and Spain agreed to peace terms in the Treaty of the Pyrenees.

The Electorate of Bavaria was a quasi-independent hereditary electorate of the Holy Roman Empire from 1623 to 1806, when it was succeeded by the Kingdom of Bavaria.

Austria and Prussia were the most powerful German states in the Holy Roman Empire by the 18th and 19th centuries and had engaged in a struggle for supremacy among smaller German kingdoms. The rivalry was characterized by major territorial conflicts and economic, cultural, and political aspects. Therefore, the rivalry was an important element of the German question in the 19th century.

The League of the Rhine was a defensive union of more than 50 German princes and their cities along the River Rhine, formed on 14 August 1658 by Louis XIV of France and negotiated by Cardinal Mazarin, Hugues de Lionne and Johann Philipp von Schönborn.

The Swedish wars on Bremen were fought between the Swedish Empire and the Hanseatic town of Bremen in 1654 and 1666. Bremen claimed to be subject to the Holy Roman Emperor, maintaining Imperial immediacy, while Sweden claimed Bremen to be a mediatised part of her dominions of Bremen-Verden, themselves territories immediately beneath the emperor. Sweden was able to gain some territory, but despite forcing a formal oath of allegiance on Bremen, did not gain control of the town.

The Imperial Diet was the deliberative body of the Holy Roman Empire. It was not a legislative body in the contemporary sense; its members envisioned it more like a central forum where it was more important to negotiate than to decide.

The imperial villages were the smallest component entities of the Holy Roman Empire. They possessed imperial immediacy, having no lord but the Emperor, but were not estates. They were unencircled and did not have representation in the Imperial Diet. In all these respects they were similar to the Imperial Knights. The inhabitants of imperial villages were free men.

The dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire occurred on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, abdicated his title and released all Imperial states and officials from their oaths and obligations to the empire. Since the Middle Ages, the Holy Roman Empire had been recognized by Western Europeans as the legitimate continuation of the ancient Roman Empire due to its emperors having been proclaimed as Roman emperors by the papacy. Through this Roman legacy, the Holy Roman Emperors claimed to be universal monarchs whose jurisdiction extended beyond their empire's formal borders to all of Christian Europe and beyond. The decline of the Holy Roman Empire was a long and drawn-out process lasting centuries. The formation of the first modern sovereign territorial states in the 16th and 17th centuries, which brought with it the idea that jurisdiction corresponded to actual territory governed, threatened the universal nature of the Holy Roman Empire.

The itio in partes was a procedure of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire between 1648 and 1806. In this procedure, the members of the diet divided into two bodies (corpora), the Corpus Evangelicorum and the Corpus Catholicorum, irrespective of the colleges to which they otherwise belonged. That is, the Protestant (Evangelical) members of the College of Electors, the College of Princes and the College of Cities gathered together separately from the Catholic members of the same. The two bodies then negotiated with each other, but debated and voted among themselves. A decision was reached only when both bodies agreed. The itio in partes could be invoked whenever there was a unanimous vote of one body. At first, it could only be invoked in matters affecting religion, but gradually this requirement was dropped.

A Reichskrieg was a war fought by the Holy Roman Empire as a whole against a common enemy. After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, a Reichskrieg was a formal state of war that could only be declared by the Imperial Diet.