Tell Abu Hureyra is a prehistoric archaeological site in the Upper Euphrates valley in Syria. The tell was inhabited between 13,300 and 7,800 cal. BP in two main phases: Abu Hureyra 1, dated to the Epipalaeolithic, was a village of sedentary hunter-gatherers; Abu Hureyra 2, dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, was home to some of the world's first farmers. This almost continuous sequence of occupation through the Neolithic Revolution has made Abu Hureyra one of the most important sites in the study of the origins of agriculture.

The Kalambo Falls on the Kalambo River is a 235-metre (772 ft) single-drop waterfall on the border of Zambia and Rukwa Region, Tanzania at the southeast end of Lake Tanganyika. The falls are some of the tallest uninterrupted falls in Africa. Downstream of the falls is the Kalambo Gorge, which has a width of about 1 km and a depth of up to 300 m, running for about 5 km before opening out into the Lake Tanganyika rift valley. The Kalambo waterfall is the tallest waterfall in both Tanzania and Zambia. The expedition which mapped the falls and the area around it was in 1928 and led by Enid Gordon-Gallien. Initially it was assumed that the height of falls exceeded 300 m, but measurements in the 1920s gave a more modest result, above 200 m. Later measurements, in 1956, gave a result of 221 m. After this several more measurements have been made, each with slightly different results. The width of the falls is 3.6–18 m.

Wilton is a term archaeologists use to generalize archaeological sites and cultures that share similar stone and non-stone technology dating from 8,000-4,000 years ago. Archaeologists often refer to Wilton as a technocomplex, or Industry. Technological industries are defined by a common tradition of stone tool assemblages, but these technological industries extend to common cultural behaviors. As such, archaeologists use these industries to define a discrete cultural taxonomy. However, technological industries have the potential to generalize different cultures and communities at regional scales that, in more local settings, are distinguishable in both technology and cultural behaviors.

The Great Serpent Mound is a 1,348-feet-long (411 m), three-feet-high prehistoric effigy mound located in Peebles, Ohio. It was built on what is known as the Serpent Mound crater plateau, running along the Ohio Brush Creek in Adams County, Ohio. The mound is the largest serpent effigy known in the world.

The Ertebølle culture is a hunter-gatherer and fisher, pottery-making culture dating to the end of the Mesolithic period. The culture was concentrated in Southern Scandinavia. It is named after the type site, a location in the small village of Ertebølle on Limfjorden in Danish Jutland. In the 1890s the National Museum of Denmark excavated heaps of oyster shells there, mixed with mussels, snails, bones, and artefacts of bone, antler, and flint, which were evaluated as kitchen middens, or refuse dumps. Accordingly, the culture is less-commonly named the Kitchen Midden. As it is approximately identical to the Ellerbek culture of Schleswig-Holstein, the combined name, Ertebølle-Ellerbek is often used. The Ellerbek culture is named after a type site in Ellerbek, a community on the edge of Kiel, Germany.

Svarthola or Vistehola is a cave and an archaeological site, located in Randaberg municipality in Rogaland county, Norway. The 9 m (30 ft) deep cavern is located on the Viste farm, about 10 km (6.2 mi) northwest of the city of Stavanger, situated near the shore of the Visteviga bay, at the mouth of the Hafrsfjorden. The site has yielded numerous Neolithic artifacts that have been excavated and discovered in and around the cave.

The Hohokam Pima National Monument is an ancient Hohokam village within the Gila River Indian Community, near present-day Sacaton, Arizona. The monument features the archaeological site Snaketown 30 miles (48 km) southeast of Phoenix, Arizona, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964. The area was further protected by declaring it a national monument in 1972, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

Kafue National Park is the largest national park in Zambia, covering an area of about 22,400 km2. It is the second largest national park in Africa and is home to 152 different species of mammals. There are also 515 bird species, 70 reptile species, 58 species of fish and 36 amphibious species.

The Itezhi-Tezhi Dam on the Kafue River in west-central Zambia was built between 1974 and 1977 at the Itezhi-Tezhi Gap, in a range of hills through which the river had eroded a narrow valley, leading to the broad expanse of the wetlands known as the Kafue Flats. The town of Itezhi-Tezhi is to the east side of the dam.

The Lochinvar National Park lies south west of Lusaka in Zambia, on the south side of the Kafue River.

The Kafue Flats are a vast area of swamp, open lagoon and seasonally inundated flood-plain on the Kafue River in the Southern, Central and Lusaka provinces of Zambia. They are a shallow flood plain 240 km (150 mi) long and about 50 km (31 mi) wide, flooded to a depth of less than a meter in the rainy season, and drying out to a clayey black soil in the dry season.

Enkapune Ya Muto, also known as Twilight Cave, is a site spanning the late Middle Stone Age to the Late Stone Age on the Mau Escarpment of Kenya. This time span has allowed for further study of the transition from the Middle Stone Age to the Late Stone Age. In particular, the changes in lithic and pottery industries can be tracked over these time periods as well as transitions from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a herding lifestyle. Beads made of perforated ostrich egg shells found at the site have been dated to 40,000 years ago. The beads found at the site represent the early human use of personal ornaments. Inferences pertaining to climate and environment changes during the pre-Holocene and Holocene period have been made based from faunal remains based in this site.

Border Cave is an archaeological site located in the western Lebombo Mountains in Kwazulu-Natal. The rock shelter has one of the longest archaeological records in southern Africa, which spans from the Middle Stone Age to the Iron Age.

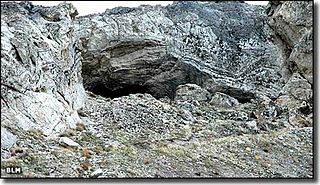

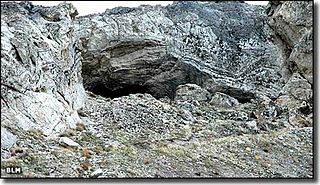

Lovelock Cave (NV-Ch-18) is a North American archaeological site previously known as Sunset Guano Cave, Horseshoe Cave, and Loud Site 18. The cave is about 150 feet (46 m) long and 35 feet (11 m) wide. Lovelock Cave is one of the most important classic sites of the Great Basin region because the conditions of the cave are conducive to the preservation of organic and inorganic material. The cave was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 24, 1984. It was the first major cave in the Great Basin to be excavated, and the Lovelock Cave people are part of the University of California Archaeological Community's Lovelock Cave Station.

Taforalt, or Grotte des Pigeons, is a cave in the province of Berkane, Aït Iznasen region, Morocco, possibly the oldest cemetery in North Africa. It contained at least 34 Iberomaurusian adolescent and adult human skeletons, as well as younger ones, from the Upper Palaeolithic between 15,100 and 14,000 calendar years ago. There is archaeological evidence for Iberomaurusian occupation at the site between 23,200 and 12,600 calendar years ago, as well as evidence for Aterian occupation as old as 85,000 years.

Elands Bay Cave is located near the mouth of the Verlorenvlei estuary on the Atlantic coast of South Africa's Western Cape Province. The climate has continuously become drier since the habitation of hunter-gatherers in the Later Pleistocene. The archaeological remains recovered from previous excavations at Elands Bay Cave have been studied to help answer questions regarding the relationship of people and their landscape, the role of climate change that could have determined or influenced subsistence changes, and the impact of pastoralism and agriculture on hunter-gatherer communities.

Melkhoutboom Cave is an archaeological site dating to the Later Stone Age, located in the Zuurberg Mountains, Cape Folded Mountain Belt, in the Addo Elephant National Park, Sarah Baartman District Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa.

Ifri Oudadane is an archaeological site in the northeastern Rif region of Morocco. It is located on the southwestern coast of the Cape Three Forks on the Mediterranean Sea, and is one of the most important sites in the northwestern Maghreb region of Africa. Discovered during road construction, the site consists of a fairly large rock shelter above the modern coastline, the site has been excavated since 2006 by a team of Moroccan and German archaeologists. Although much is known about the transition of humans from hunter gatherer groups to food production in Europe and the Middle East, much of North Africa has not been researched. Ifri Oudadane is one of the first of such sites in North Africa. Dated to between 11000 and 5700 years BP, the site contains evidence that documents the shift of local inhabitants from hunter-gatherer groups to food producers. Such elements of change found at Ifri Oudadane include evidence of animal husbandry, domestication of legumes, and decoration of pottery. The site is known to contain the earliest dated crop in Northern Africa, a lentil.

Matupi Cave is a cave in the Mount Hoyo massif of the Ituri Rainforest, Democratic Republic of the Congo, where archaeologists have found evidence for Late Stone Age human occupation spanning over 40,000 years. The cave has some of the earliest evidence in the world for microlithic tool technologies.

Jebel Moya is an archaeological site in the southern Gezira Plain, Sudan, approximately 250 km south southeast of Khartoum. Dating between 5000 BCE-500 CE and roughly 104,000 m2 in area, the site is one of the largest pastoralist cemeteries in Africa with over 3,000 burials excavated thus far. The site was first excavated by Sir Henry Wellcome from 1911 to 1914. Artifacts found at the site suggest trade routes between Jebel Moya and its surrounding areas, even as far as Egypt.