Related Research Articles

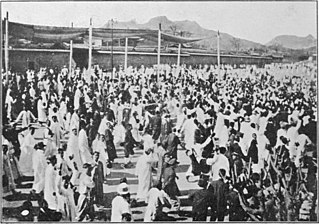

The March First Movement was a series of protests against Japanese colonial rule that was held throughout Korea and internationally by the Korean diaspora beginning on March 1, 1919. Protests were largely concentrated in March and April, although related protests continued until 1921. In South Korea, the movement is remembered as a landmark event of not only the Korean independence movement, but of all of Korean history.

The Korea Liberation Corps (Korean: 대한광복단) was a Korean association formed in 1913 to fight against Japanese rule. At its height its members numbered about 200. The Korea Liberation Association was a successor organization to Korea Liberation Corps.

Shin Chae-ho, or Sin Chaeho, was a Korean independence activist, historian, anarchist, nationalist, and a founder of Korean nationalist historiography. He is held in high esteem in both North and South Korea.

Min Yeong-hwan was a politician, diplomat, and general of the Korean Empire and known as a conservative proponent for reform. He was born in Seoul into the powerful Yeoheung Min clan which Heungseon Daewongun hated, and committed suicide as an act of resistance against the Eulsa Treaty imposed by Japan on Korea. He is remembered today for his efforts on behalf of Korean independence in the waning days of the Joseon period.

Yi Gwangsu was a Korean writer, Korean independence activist, and later collaborator with Imperial Japan. Yi is best known for his novel Mujeong, which is often described as the first modern Korean novel.

Lyuh Woon-hyung, also known by his art name Mongyang, was a Korean independence activist and reunification activist.

The Korean National Association, also known as All Korea Korean National Association, was a political organization established on February 1, 1909, to fight Japan's colonial policies and occupation in Korea. It was founded in San Francisco by the intellectual scholar and Korean Independence activist Ahn Changho, and represented the interests of Koreans in the United States, Russian Far East, and Manchuria during the Korean Independence Movement.

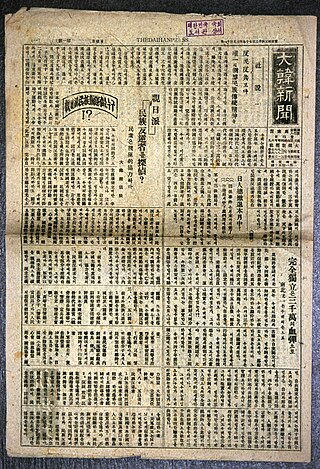

Modern newspapers have been published in Korea since 1881, with the first native Korean newspaper being published in 1883.

The Svobodny Incident, also known as the Jayu City Incident and the Heukha Incident, occurred on June 28, 1921, in Svobodny in the Far East Republic where the Korean exiled independence fighters who refused to accept command of the Red Army were surrounded and suppressed.

The Korean Independence Corps (Korean: 대한독립군단) was a militant Korean independence organization that united the Korean Independence armies until its dissolution after the Free City Incident, reorganization in Manchuria, and its final dissolution.

Seo Il was a Daejonggyo priest and independence activist who was credited for creating famous generals of the independence army, such as General Kim Jwa-jin whom they participated in the Battle of Cheongsanri while Seo-Il served as the president of the Northern Military Administration Office and the Korean Independence Corps.

The Korean Righteous Corps (Korean: 대한정의단) was a short-lived militant Korean independence activist organization from May to October 1919. It was founded as a union of Daejong followers and believers of other religions, such as the Confucian Church. The Korean Justice Corps aimed to carry out a secret armed struggle to achieve independence, and its leader was Seo Il. The Korean Justice Corps contributed to promoting the necessity of the anti-Japanese independence struggle and promoting national consciousness. They reorganized into the Northern Military Government but they changed the name to Northern Military Administration Office under the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea.

The Sinhanch'on Incident or the April Disaster (4월참변) was a massacre of Korean civilians by Japanese soldiers in the Korean enclave Sinhanch'on, Vladivostok, Far Eastern Republic beginning on April 4, 1920. The massacre lasted for several days. It is not known how many were killed, although one estimate puts the number at several hundred.

Taehan Sinmun, or The Daihan Press, was a Korean-language newspaper published in the Korean Empire from 1907 to 1910.

Haejo Sinmun was a daily Korean-language newspaper published in the Korean enclave Shinhanchon, Vladivostok, Russian Empire in 1908. It was the first Korean-language daily newspaper published in Russia.

Taedong Kongbo was a Korean-language newspaper published in Vladivostok, Russian Empire from 1908 to 1910. It briefly changed its name to Taedong Sinbo before its closure.

Taeyangbo was a Korean-language newspaper published in Shinhanchon, Vladivostok, Russian Empire in 1911. It was written entirely in the native Korean script Hangul.

Kwŏnŏp Sinmun was a weekly Korean-language newspaper published in Shinhanchon, Vladivostok, Russian Empire from 1912 to 1914. It was written in the native Korean script Hangul, and was named for and was the official publication of the Korean organization Gwoneophoe.

Ch'ŏnggu Sinbo was a weekly Korean-language newspaper published in Nikolsk-Ussuriysky, Russian Empire from 1917 to 1919. It was renamed to Hanjok Kongbo shortly before its closure.

Sinhanch'on was an enclave of Koreans in Vladivostok that existed between 1911 and 1937, during which time the city was controlled for periods by the Russian Empire, Far Eastern Republic and finally the Soviet Union.

References

- ↑ Dae-Yeong, Youn (2014). "The Loss of Vietnam: Korean Views of Vietnam in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 9 (1): 85. doi:10.1525/vs.2014.9.1.62. ISSN 1559-372X. JSTOR 10.1525/vs.2014.9.1.62.

- ↑ Ban, Byung Yool (2016). "Danjae Sin Chae-ho's Nationalist Actvities [sic] in the Russian Maritime Province". 한국학논총 (in Korean). 46: 365–392. ISSN 1225-9977.

- ↑ 김, 정인. "대한민국 임시정부 (大韓民國 臨時政府)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-13.

- ↑ Yoon, In-Jin (March 2012). "Migration and the Korean Diaspora: A Comparative Description of Five Cases". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 38 (3): 413–435. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2012.658545. ISSN 1369-183X. S2CID 143696849.

- ↑ Lee 2000, p. 7.

- ↑ Kwak, Yeon-soo (2019-03-14). "Tracing freedom fighters in Russian Far East". The Korea Times . Retrieved 2024-01-21.

- ↑ 정, 진석 (2020-08-02). "[제국의 황혼 '100년전 우리는'][144] 연해주의 抗日신문과 언론인들". The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 "권업회[勸業會]". 우리역사넷. Retrieved 2024-02-13.

- 1 2 "러시아지역". 우리역사넷. National Institute of Korean History . Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "러시아지역 한인신문 약사". 재외동포신문 (in Korean). 2003-07-14. Retrieved 2024-02-13.

- ↑ "엄인섭 (嚴仁燮)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-13.

- ↑ 이, 재석; 이, 세중; 강, 민아 (December 2021). 밀정, 우리 안의 적 (in Korean). 시공사. ISBN 979-11-6579-841-3.

- 1 2 배, 항섭 (2004-05-31). "[개교 100주년]조부의 유지이어 교육사업과 항일투쟁에 매진". 고대신문 (in Korean). Retrieved 2024-02-13.

Sources

- Lee, Kwang-kyu (2000), Overseas Koreans, Seoul: Jimoondang, ISBN 89-88095-18-9