Ancient Sparta

King Leotychides used the gathering of the Gymnopaedia to deliver an insult to the recently deposed king Demaratus, asking him via messenger what it felt like to hold public office after being a king. He responded calmly that he had experience in both unlike Leotychides himself, also saying that this question would be the beginning of either great fortune or great evil for Sparta. He then left the festival and made a sacrifice to Zeus. (Hdt. 6.67). [20]

The Gymnopaedia was important enough to the Spartans that they would avoid leaving the city even if called on. Thucydides explains an occasion of this in History of the Peloponnesian War (Thuc. 5.82). [21] The Argive democrats knew how important the festival was to the Spartans, and waited until the festival began in order to attack the ruling oligarchs who were allied with Sparta. The Spartans eventually postponed the Gymnopaedia, but the oligarchs had already been defeated by this time. [6]

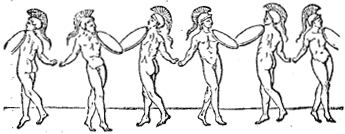

The festival was of such importance to the Spartans that even king Agesilaus participated despite his lameness, but was hidden in the back of the group so no one could see his physical flaws. [22] Xenophon writes that Agesilaus was extremely devoted to religion (Xen. Ages. 3.2), so he would have seen this participation as a duty. [23]

The news of Spartan loss at the battle of Leuctra reached Sparta during the final day of the Gymnopaedia. [12] Despite the large negative effect this news would have on Sparta's power, the ephors would not allow any dances to be cancelled or for the celebrations to be changed. When the families of the deceased soldiers had been told of the news, the ephors brought the festival to a close (Plut. Ages. 29. 2-3). [24] Xenophon expands on this information, saying that the ephors instructed the families of the dead to suffer their grief in silence so as not to disrupt the festival. The following day all those who had lost relatives could be seen smiling and being cheerful in public. Those who had family members at the battle who were still living were sad and worried for their loved ones (Xen. Hell. 6.4). [25]

Plutarch says Lichas, a wealthy Spartan, gained fame for entertaining many of the strangers at a "boys gymnastic festival" (Plut. Cim. 10, 5) [26] This festival was interpreted by Xenophon to be the Gymnopaedia. [27]