Related Research Articles

Rickettsia is a genus of nonmotile, gram-negative, nonspore-forming, highly pleomorphic bacteria that may occur in the forms of cocci, bacilli, or threads. The genus was named after Howard Taylor Ricketts in honor of his pioneering work on tick-borne spotted fever.

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. A typical life cycle involves flightless females giving live birth to female nymphs—who may also be already pregnant, an adaptation scientists call telescoping generations—without the involvement of males. Maturing rapidly, females breed profusely so that the number of these insects multiplies quickly. Winged females may develop later in the season, allowing the insects to colonize new plants. In temperate regions, a phase of sexual reproduction occurs in the autumn, with the insects often overwintering as eggs.

Enterobacterales is an order of Gram-negative, non-spore forming, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria with the class Gammaproteobacteria. The type genus of this order is Enterobacter.

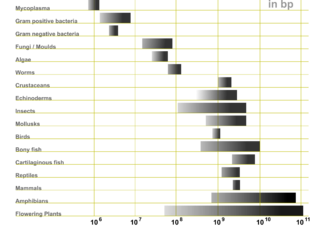

Genome size is the total amount of DNA contained within one copy of a single complete genome. It is typically measured in terms of mass in picograms or less frequently in daltons, or as the total number of nucleotide base pairs, usually in megabases. One picogram is equal to 978 megabases. In diploid organisms, genome size is often used interchangeably with the term C-value.

Buchnera aphidicola, a member of the Pseudomonadota and the only species in the genus Buchnera, is the primary endosymbiont of aphids, and has been studied in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Buchnera is believed to have had a free-living, Gram-negative ancestor similar to a modern Enterobacterales, such as Escherichia coli. Buchnera is 3 μm in diameter and has some of the key characteristics of its Enterobacterales relatives, such as a Gram-negative cell wall. However, unlike most other Gram-negative bacteria, Buchnera lacks the genes to produce lipopolysaccharides for its outer membrane. The long association with aphids and the limitation of crossover events due to strictly vertical transmission has seen the deletion of genes required for anaerobic respiration, the synthesis of amino sugars, fatty acids, phospholipids, and complex carbohydrates. This has resulted not only in one of the smallest known genomes of any living organism, but also one of the most genetically stable.

A bacteriocyte, also known as a mycetocyte, is a specialized adipocyte found primarily in certain insect groups such as aphids, tsetse flies, German cockroaches, weevils. These cells contain endosymbiotic organisms such as bacteria and fungi, which provide essential amino acids and other chemicals to their host. Bacteriocytes may aggregate into a specialized organ called the bacteriome.

"Candidatus Carsonella ruddii" is an obligate endosymbiotic Gammaproteobacterium with one of the smallest genomes of any characterised bacteria.

Photorhabdus luminescens is a Gammaproteobacterium of the family Morganellaceae, and is a lethal pathogen of insects.

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) is a DNA virus from the genus Begomovirus and the family Geminiviridae. TYLCV causes the most destructive disease of tomato, and it can be found in tropical and subtropical regions causing severe economic losses. This virus is transmitted by an insect vector from the family Aleyrodidae and order Hemiptera, the whitefly Bemisia tabaci, commonly known as the silverleaf whitefly or the sweet potato whitefly. The primary host for TYLCV is the tomato plant, and other plant hosts where TYLCV infection has been found include eggplants, potatoes, tobacco, beans, and peppers. Due to the rapid spread of TYLCV in the last few decades, there is an increased focus in research trying to understand and control this damaging pathogen. Some interesting findings include the virus being sexually transmitted from infected males to non-infected females, and an evidence that TYLCV is transovarially transmitted to offspring for two generations.

Nancy A. Moran is an American evolutionary biologist and entomologist, University of Texas Leslie Surginer Endowed Professor, and co-founder of the Yale Microbial Diversity Institute. Since 2005, she has been a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences. Her seminal research has focused on the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum and its bacterial symbionts including Buchnera (bacterium). In 2013, she returned to the University of Texas at Austin, where she continues to conduct research on bacterial symbionts in aphids, bees, and other insect species. She has also expanded the scale of her research to bacterial evolution as a whole. She believes that a good understanding of genetic drift and random chance could prevent misunderstandings surrounding evolution. Her current research goal focuses on complexity in life-histories and symbiosis between hosts and microbes, including the microbiota of insects.

Acyrthosiphon pisum, commonly known as the pea aphid, is a sap-sucking insect in the family Aphididae. It feeds on several species of legumes worldwide, including forage crops, such as pea, clover, alfalfa, and broad bean, and ranks among the aphid species of major agronomical importance. The pea aphid is a model organism for biological study whose genome has been sequenced and annotated.

Bacterial genomes are generally smaller and less variant in size among species when compared with genomes of eukaryotes. Bacterial genomes can range in size anywhere from about 130 kbp to over 14 Mbp. A study that included, but was not limited to, 478 bacterial genomes, concluded that as genome size increases, the number of genes increases at a disproportionately slower rate in eukaryotes than in non-eukaryotes. Thus, the proportion of non-coding DNA goes up with genome size more quickly in non-bacteria than in bacteria. This is consistent with the fact that most eukaryotic nuclear DNA is non-gene coding, while the majority of prokaryotic, viral, and organellar genes are coding. Right now, we have genome sequences from 50 different bacterial phyla and 11 different archaeal phyla. Second-generation sequencing has yielded many draft genomes ; third-generation sequencing might eventually yield a complete genome in a few hours. The genome sequences reveal much diversity in bacteria. Analysis of over 2000 Escherichia coli genomes reveals an E. coli core genome of about 3100 gene families and a total of about 89,000 different gene families. Genome sequences show that parasitic bacteria have 500–1200 genes, free-living bacteria have 1500–7500 genes, and archaea have 1500–2700 genes. A striking discovery by Cole et al. described massive amounts of gene decay when comparing Leprosy bacillus to ancestral bacteria. Studies have since shown that several bacteria have smaller genome sizes than their ancestors did. Over the years, researchers have proposed several theories to explain the general trend of bacterial genome decay and the relatively small size of bacterial genomes. Compelling evidence indicates that the apparent degradation of bacterial genomes is owed to a deletional bias.

Serratia symbiotica is a species of bacteria that lives as a symbiont of aphids. In the aphid Cinara cedri, it coexists with Buchnera aphidicola, given the latter cannot produce tryptophan. It is also known to habitate in Aphis fabae. Together with other endosymbionts, it provides aphids protection against parasitoids.

Regiella insecticola is a species of bacteria, that lives as a symbiont of aphids. It shows a relationship with Photorhabdus species, together with Hamiltonella defensa. Together with other endosymbionts, it provides aphids protection against parasitoids.

Hamiltonella is a genus of Enterobacteria in the Gammaproteobacteria. Hamiltonella defensa is a model organism for defensive symbiosis, protecting pea aphids from parasitoid wasps. Hamiltonella has also been found as a nutritional mutualistic endosymbiont in Whiteflies.

Blochmannia is a genus of symbiotic bacteria found in carpenter ant. There are over 1000 species of these ants and, as of 2014, of the over 30 species of carpenter ant that have been investigated, all contain some form of Blochmannia. The bacteria filled cells currently known as members of the genus Blochmannia were first discovered by zoologist F. Blochmann in the ovaries and midguts of insects in the 1880s. In 2000 Candidatus Blochmannia was proposed as its own genus.

Cassava brown streak virus is a species of positive-strand RNA viruses in the genus Ipomovirus and family Potyviridae which infects plants. Member viruses are unique in their induction of pinwheel, or scroll-shaped inclusion bodies in the cytoplasm of infected cells. Cylindrical inclusion bodies include aggregations of virus-encoded helicase proteins. These inclusion bodies are thought to be sites of viral replication and assembly, making then an important factor in the viral lifecycle. Viruses from both the species Cassava brown streak virus and Ugandan cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV), lead to the development of Cassava Brown Streak Disease (CBSD) within cassava plants.

Sweet potato leaf curl virus is commonly abbreviated SPLCV. Select isolates are referred to as SPLCV followed by an abbreviation of where they were isolated. For example, the Brazilian isolate is referred to as SPLCV-Br.

Reductive evolution is the process by which microorganisms remove genes from their genome. It can occur when bacteria found in a free-living state enter a restrictive state or are completely absorbed by another organism becoming intracellular (symbiogenesis). The bacteria will adapt to survive and thrive in the restrictive state by altering and reducing its genome to get rid of the newly redundant pathways that are provided by the host. In an endosymbiont or symbiogenesis relationship where both the guest and host benefit, the host can also undergo reductive evolution to eliminate pathways that are more efficiently provided for by the guest.

Candidatus Arsenophonus arthropodicus is a Gram-negative and intracellular secondary (S) endosymbiont that belongs to the genus Arsenophonus. This bacterium is found in the Hippoboscid louse fly, Pseudolynchia canariensis. S-endosymbionts are commonly found in distinct tissues. Strains of recovered Arsenophonus found in arthropods share 99% sequence identification in the 16S rRNA gene across all species. Arsenophonus-host interactions involve parasitism and mutualism, including a popular mechanism of "male-killing" found commonly in a related species, Arsenophonus nasoniae. This species is considered "Ca. A. arthropodicus" due it being as of yet uncultured.

References

- ↑ Moran NA, Russell JA, Koga R, Fukatsu T (June 2005). "Evolutionary relationships of three new species of Enterobacteriaceae living as symbionts of aphids and other insects". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 71 (6): 3302–10. Bibcode:2005ApEnM..71.3302M. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.6.3302-3310.2005. PMC 1151865 . PMID 15933033.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Degnan PH, Yu Y, Sisneros N, Wing RA, Moran NA (June 2009). "Hamiltonella defensa, genome evolution of protective bacterial endosymbiont from pathogenic ancestors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (22): 9063–8. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9063D. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900194106 . PMC 2690004 . PMID 19451630.

- 1 2 3 4 Rao Q, Wang S, Su YL, Bing XL, Liu SS, Wang XW (July 2012). "Draft genome sequence of "Candidatus Hamiltonella defensa," an endosymbiont of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci". Journal of Bacteriology. 194 (13): 3558. doi:10.1128/JB.00069-12. PMC 3434728 . PMID 22689243.

- 1 2 3 Gross R, Vavre F, Heddi A, Hurst GD, Zchori-Fein E, Bourtzis K (September 2009). "Immunity and symbiosis". Molecular Microbiology. 73 (5): 751–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06820.x . PMID 19656293. S2CID 37520548.

- ↑ Team, BioModels.net. "BioModels Database". www.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Degnan PH, Yu Y, Sisneros N, Wing RA, Moran NA (June 2009). "Hamiltonella defensa, genome evolution of protective bacterial endosymbiont from pathogenic ancestors". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106 (22): 9063–9068. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9063D. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900194106 . PMC 2690004 . PMID 19451630.