Colonel Reginald Edward Harry Dyer, was a British military officer in the Bengal Army and later the newly constituted British Indian Army. His military career began in the regular British Army, but he soon transferred to the presidency armies of India.

The non-cooperation movement was a political campaign launched on 4 September 1920 by Mahatma Gandhi to have Indians revoke their cooperation from the British government, with the aim of persuading them to grant self-governance.

The Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919, popularly known as the Rowlatt Act, was a law, applied during the British India period. It was a legislative council act passed by the Imperial Legislative Council in Delhi on 18 March 1919, indefinitely extending the emergency measures of preventive indefinite detention, imprisonment without trial and judicial review enacted in the Defence of India Act 1915 during the First World War. It was enacted in the light of a perceived threat from revolutionary nationalists of re-engaging in similar conspiracies as had occurred during the war which the Government felt the lapse of the Defence of India Act would enable.

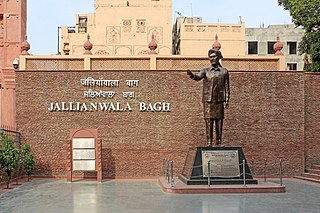

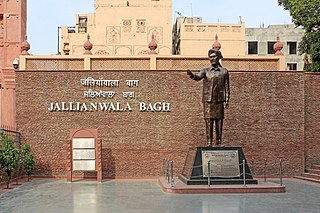

Jallianwala Bagh is a historic garden and memorial of national importance close to the Golden Temple complex in Amritsar, Punjab, India, preserved in the memory of those wounded and killed in the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre that took place on the site on the festival of Baisakhi Day, 13 April 1919. The 7-acre (28,000 m2) site houses a museum, gallery and several memorial structures. It is managed by the Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial Trust, and was renovated between 2019 and 2021.

Udham Singh was an Indian revolutionary belonging to Ghadar Party and HSRA, best known for assassinating Michael O'Dwyer, the former lieutenant governor of the Punjab in India, on 13 March 1940. The assassination was done in revenge for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919, for which O'Dwyer was responsible and of which Singh himself was a survivor. Singh was subsequently tried and convicted of murder and hanged in July 1940. While in custody, he used the name 'Ram Mohammad Singh Azad', which represents the three major religions in India and his anti-colonial sentiment.

Saifuddin Kitchlew was an Indian independence activist, barrister, politician and later a leader of the peace movement. A member of Indian National Congress, he first became Punjab Provincial Congress Committee head and later the General Secretary of the All India Congress Committee in 1924. He is most remembered for the protests in Punjab after the implementation of Rowlatt Act in March 1919, after which on 10 April, he and another leader Satyapal, were secretly sent to Dharamsala. A public protest rally against their arrest and that of Gandhi, on 13 April 1919 at Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar, led to the infamous Jallianwala Bagh massacre. He was also a founding member of Jamia Millia Islamia. He was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize in 1952.

Sir Michael Francis O'Dwyer was an Irish colonial officer in the Indian Civil Service (ICS) and later the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, British India, between 1913 and 1919.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, also known as the Amritsar massacre, took place on 13 April 1919. A large crowd had gathered at the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, British India, during the annual Baishakhi fair to protest against the Rowlatt Act and the arrest of pro-Indian independence activists Saifuddin Kitchlew and Satyapal. In response to the public gathering, the temporary brigadier general R. E. H. Dyer surrounded the people with his Gurkha and Sikh infantry regiments of the British Indian Army. The Jallianwala Bagh could only be exited on one side, as its other three sides were enclosed by buildings. After blocking the exit with his troops, Dyer ordered them to shoot at the crowd, continuing to fire even as the protestors tried to flee. The troops kept on firing until their ammunition was low and they were ordered to stop. Estimates of those killed vary from 379 to 1,500 or more people; over 1,200 others were injured, of whom 192 sustained serious injuries.

Gurmukh Singh Musafir was an Indian politician and Punjabi language writer. He was the 5th Chief Minister of Punjab from 1 November 1966 to 8 March 1967.

The Defence of India Act 1915, also referred to as the Defence of India Regulations Act, was an emergency criminal law enacted by the Governor-General of India in 1915 with the intention of curtailing the nationalist and revolutionary activities during and in the aftermath of the First World War. It was similar to the British Defence of the Realm Acts, and granted the Executive very wide powers of preventive detention, internment without trial, restriction of writing, speech, and of movement. However, unlike the English law which was limited to persons of hostile associations or origin, the Defence of India act could be applied to any subject of the King, and was used to an overwhelming extent against Indians. The passage of the act was supported unanimously by the non-official Indian members in the Viceroy's legislative council, and was seen as necessary to protect against British India from subversive nationalist violence. The act was first applied during the First Lahore Conspiracy trial in the aftermath of the failed Ghadar Conspiracy of 1915, and was instrumental in crushing the Ghadr movement in Punjab and the Anushilan Samiti in Bengal. However its widespread and indiscriminate use in stifling genuine political discourse made it deeply unpopular, and became increasingly reviled within India. The extension of the law in the form of the Rowlatt Act after the end of World War I was opposed unanimously by the non-official Indian members of the Viceroy's council. It became a flashpoint of political discontent and nationalist agitation, culminating in the Rowlatt Satyagraha. The act was re-enacted during World War II as Defence of India act 1939. Independent India retained the law in a number of amended forms, which have seen use in proclaimed states of national emergency including Sino-Indian War, Bangladesh crisis, The Emergency of 1975 and subsequently the Punjab insurgency.

The Sedition Committee, usually known as the Rowlatt Committee, was a committee of inquiry appointed in 1917 by the British Indian Government with Sidney Rowlatt, an Anglo-Egyptian judge, as its president, charged with evaluating the threat posed to British rule by the revolutionary movement and determining the legal changes necessary to deal with it.

Sir Sidney Arthur Taylor Rowlatt, KCSI, PC was a British barrister and judge, remembered in part for his presidency of the sedition committee that bore his name, created in 1918 by the imperial government to subjugate and control the independence movement in British India, especially Bengal and the Punjab. The committee gave rise to the Rowlatt Act, an extension of the Defence of India Act 1915.

Benjamin Guy Horniman was a British-Indian journalist and editor of The Bombay Chronicle, particularly notable for his support of Indian independence.

Nick Lloyd FRHS, is Professor of Modern Warfare at King's College London. He has written several books on the First World War.

Sir Miles Irving CIE, OBE was an English Indian Civil Service officer. As Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar, the senior government official in charge, he transferred the city's administration to Colonel Reginald Dyer in April 1919, which helped to precipitate the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

Satyapal was a physician and political leader in Punjab, British India, who was arrested along with Saifuddin Kitchlew on 10 April 1919, three days before the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

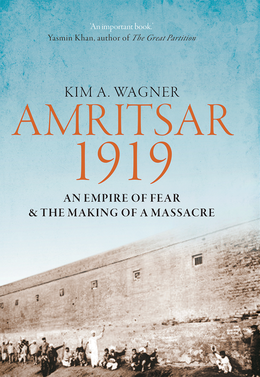

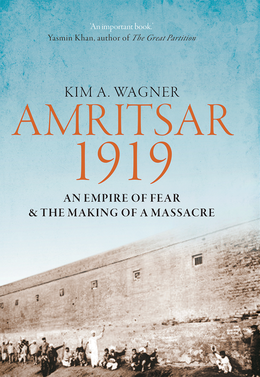

Amritsar 1919: An Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre (2019), is a book by Kim A. Wagner and published by Yale University Press, that aims to dispel myths surrounding the Jallianwala Bagh massacre that took place in Amritsar, India, on 13 April 1919.

The Patient Assassin, A True Tale of Massacre, Revenge and the Raj is a 2019 book based on the life of Indian revolutionary Udham Singh. Authored by Anita Anand, it was published by Simon & Schuster UK in April 2019 to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre in Amritsar, India.

Vishwa Nath Datta was a distinguished Indian writer, historian and professor emeritus at Kurukshetra University.

Badrul Islam Ali Khan was a barrister at Amritsar, Punjab, British India. On 19 April 1919, following the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, having been named by Hans Raj, he was arrested for setting up meetings at Jallianwala Bagh, to free Satyapal and Saifuddin Kitchlew, who had revealed the implications to Indians of the Rowlatt Act. He was later acquitted.