Dairy products or milk products, also known as lacticinia, are food products made from milk. The most common dairy animals are cow, water buffalo, nanny goat, and ewe. Dairy products include common grocery store food around the world such as yogurt, cheese, milk and butter. A facility that produces dairy products is a dairy. Dairy products are consumed worldwide to varying degrees. Some people avoid some or all dairy products because of lactose intolerance, veganism, environmental concerns, other health reasons or beliefs.

In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

A sugar substitute is a food additive that provides a sweetness like that of sugar while containing significantly less food energy than sugar-based sweeteners, making it a zero-calorie or low-calorie sweetener. Artificial sweeteners may be derived through manufacturing of plant extracts or processed by chemical synthesis. Sugar substitute products are commercially available in various forms, such as small pills, powders, and packets.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D), formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, is a form of diabetes mellitus that is characterized by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and relative lack of insulin. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent urination, fatigue and unexplained weight loss. Other symptoms include increased hunger, having a sensation of pins and needles, and sores (wounds) that heal slowly. Symptoms often develop slowly. Long-term complications from high blood sugar include heart disease, stroke, diabetic retinopathy, which can result in blindness, kidney failure, and poor blood flow in the lower-limbs, which may lead to amputations. The sudden onset of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state may occur; however, ketoacidosis is uncommon.

The Mediterranean diet is a concept first invented in 1975 by the American biologist Ancel Keys and chemist Margaret Keys. The diet took inspiration from the eating habits and traditional food typical of Crete, much of the rest of Greece, and southern Italy, and formulated in the early 1960s. It is distinct from Mediterranean cuisine, which covers the actual cuisines of the Mediterranean countries, and from the Atlantic diet of northwestern Spain and Portugal. While inspired by a specific time and place, the "Mediterranean diet" was later refined based on the results of multiple scientific studies.

Diet sodas are soft drinks which contain little or no sugar or calories. First introduced onto the market in 1949, diet sodas are typically marketed for those with diabetes or who wish to reduce their sugar or caloric intake.

A healthy diet is a diet that maintains or improves overall health. A healthy diet provides the body with essential nutrition: fluid, macronutrients such as protein, micronutrients such as vitamins, and adequate fibre and food energy.

Tagatose is a hexose monosaccharide. It is found in small quantities in a variety of foods, and has attracted attention as an alternative sweetener. It is often found in dairy products, because it is formed when milk is heated. It is similar in texture and appearance to sucrose :215 and is 92% as sweet,:198 but with only 38% of the calories.:209 Tagatose is generally recognized as safe by the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization, and has been since 2001. Since it is metabolized differently from sucrose, tagatose has a minimal effect on blood glucose and insulin levels. Tagatose is also approved as a tooth-friendly ingredient for dental products. Consumption of more than about 30 grams of tagatose in a dose may cause gastric disturbance in some people, as it is mostly processed in the large intestine, similar to soluble fiber.:214

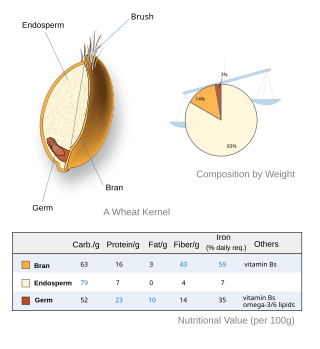

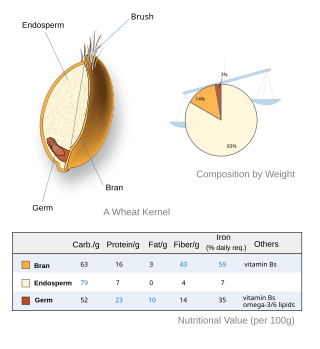

A whole grain is a grain of any cereal and pseudocereal that contains the endosperm, germ, and bran, in contrast to refined grains, which retain only the endosperm.

The main goal of diabetes management is to keep blood glucose (BG) levels as normal as possible. If diabetes is not well controlled, further challenges to health may occur. People with diabetes can measure blood sugar by various methods, such as with a BG meter or a continuous glucose monitor, which monitors over several days. Glucose can also be measured by analysis of a routine blood sample. Usually, people are recommended to control diet, exercise, and maintain a healthy weight, although some people may need medications to control their blood sugar levels. Other goals of diabetes management are to prevent or treat complications that can result from the disease itself and from its treatment.

A diabetic diet is a diet that is used by people with diabetes mellitus or high blood sugar to minimize symptoms and dangerous complications of long-term elevations in blood sugar.

A non-communicable disease (NCD) is a disease that is not transmissible directly from one person to another. NCDs include Parkinson's disease, autoimmune diseases, strokes, heart diseases, cancers, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, Alzheimer's disease, cataracts, and others. NCDs may be chronic or acute. Most are non-infectious, although there are some non-communicable infectious diseases, such as parasitic diseases in which the parasite's life cycle does not include direct host-to-host transmission.

The Western pattern diet is a modern dietary pattern that is generally characterized by high intakes of pre-packaged foods, refined grains, red meat, processed meat, high-sugar drinks, candy and sweets, fried foods, industrially produced animal products, butter and other high-fat dairy products, eggs, potatoes, corn, and low intakes of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, pasture-raised animal products, fish, nuts, and seeds.

Canagliflozin, sold under the brand name Invokana among others, is a medication used to treat type 2 diabetes. It is used together with exercise and diet. It is not recommended in type 1 diabetes. It is taken by mouth.

Empagliflozin, sold under the brand name Jardiance, among others, is an antidiabetic medication used to improve glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes. It is taken by mouth.

Added sugars or free sugars are sugar carbohydrates added to food and beverages at some point before their consumption. These include added carbohydrates, and more broadly, sugars naturally present in honey, syrup, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates. They can take multiple chemical forms, including sucrose, glucose (dextrose), and fructose.

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are beverages with added sugar. They have been described as "liquid candy". Added sugars include brown sugar, corn sweetener, corn syrup, dextrose, fructose, high fructose corn syrup, honey, invert sugar, lactose, malt syrup, maltose, molasses, raw sugar, sucrose, trehalose, and turbinado sugar. Naturally occurring sugars, such as those in fruit or milk, are not considered to be added sugars. Free sugars include monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods and beverages by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, and sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates.

An ultra-processed food (UPF) is a grouping of processed food characterized by relatively involved methods of production. There is no single definition of UPF, but they are generally understood to be an industrial creation derived from natural food or synthesized from other organic compounds. The resulting products are designed to be highly profitable, convenient, and hyperpalatable, often through food additives such as preservatives, colourings, and flavourings. UPFs have often undergone processes such as moulding/extruding, hydrogenation, or frying.

Preventive Nutrition is a branch of nutrition science with the goal of preventing, delaying, and/or reducing the impacts of disease and disease-related complications. It is concerned with a high level of personal well-being, disease prevention, and diagnosis of recurring health problems or symptoms of discomfort which are often precursors to health issues. The overweight and obese population numbers have increased over the last 40 years and numerous chronic diseases are associated with obesity. Preventive nutrition may assist in prolonging the onset of non-communicable diseases and may allow adults to experience more "healthy living years." There are various ways of educating the public about preventive nutrition. Information regarding preventive nutrition is often communicated through public health forums, government programs and policies, or nutritional education. For example, in the United States, preventive nutrition is taught to the public through the use of the food pyramid or MyPlate initiatives.

Pure, White and Deadly is a 1972 book by John Yudkin, a British nutritionist and former Chair of Nutrition at Queen Elizabeth College, London. Published in New York, it was the first publication by a scientist to anticipate the adverse health effects, especially in relation to obesity and heart disease, of the public's increased sugar consumption. At the time of publication, Yudkin sat on the advisory panel of the British Department of Health's Committee on the Medical Aspects of Food and Nutrition Policy (COMA). He stated his intention in writing the book in the last paragraph of the first chapter: "I hope that when you have read this book I shall have convinced you that sugar is really dangerous."