The Panama Canal is an artificial 82-kilometer (51-mile) waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a conduit for maritime trade between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Locks at each end lift ships up to Gatun Lake, an artificial fresh water lake 26 meters (85 ft) above sea level, created by damming the Chagres River and Lake Alajuela to reduce the amount of excavation work required for the canal. Locks then lower the ships at the other end. An average of 200 ML (52,000,000 US gal) of fresh water is used in a single passing of a ship. The canal is threatened by low water levels during droughts.

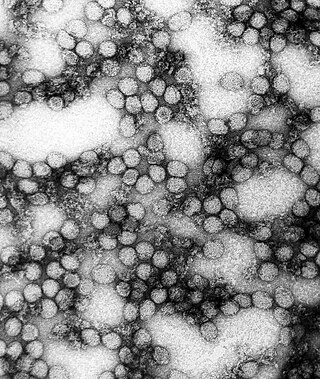

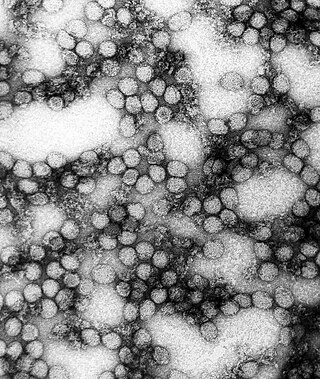

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains—particularly in the back—and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In about 15% of people, within a day of improving the fever comes back, abdominal pain occurs, and liver damage begins causing yellow skin. If this occurs, the risk of bleeding and kidney problems is increased.

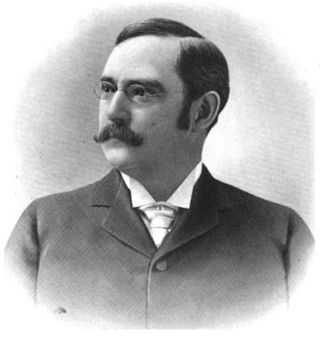

Walter Reed was a U.S. Army physician who in 1901 led the team that confirmed the theory of Cuban doctor Carlos Finlay that yellow fever is transmitted by a particular mosquito species rather than by direct contact. This insight gave impetus to the new fields of epidemiology and biomedicine, and most immediately allowed the resumption and completion of work on the Panama Canal (1904–1914) by the United States. Reed followed work started by Finlay and directed by George Miller Sternberg, who has been called the "first U.S. bacteriologist".

Arbovirus is an informal name for any virus that is transmitted by arthropod vectors. The term arbovirus is a portmanteau word. Tibovirus is sometimes used to more specifically describe viruses transmitted by ticks, a superorder within the arthropods. Arboviruses can affect both animals and plants. In humans, symptoms of arbovirus infection generally occur 3–15 days after exposure to the virus and last three or four days. The most common clinical features of infection are fever, headache, and malaise, but encephalitis and viral hemorrhagic fever may also occur.

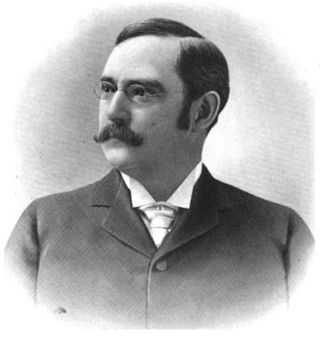

John Frank Stevens was an American civil engineer who built the Great Northern Railway in the United States and was chief engineer on the Panama Canal between 1905 and 1907. He also led the commission of American railway experts to Russia and was later President of the Interallied Technical Board.

Carlos Juan Finlay was a Cuban epidemiologist recognized as a pioneer in the research of yellow fever, determining that it was transmitted through mosquitoes Aedes aegypti.

Vector control is any method to limit or eradicate the mammals, birds, insects or other arthropods which transmit disease pathogens. The most frequent type of vector control is mosquito control using a variety of strategies. Several of the "neglected tropical diseases" are spread by such vectors.

Oswaldo Gonçalves Cruz, was a Brazilian physician, pioneer bacteriologist, epidemiologist and public health officer and the founder of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute.

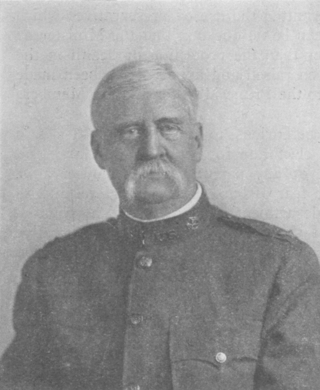

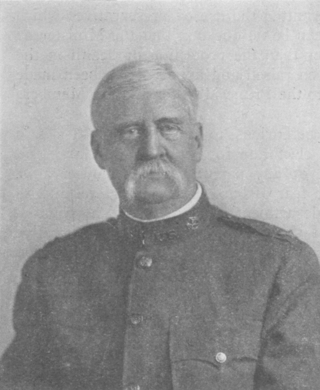

William Crawford Gorgas KCMG was a United States Army physician and 22nd Surgeon General of the U.S. Army (1914–1918). He is best known for his work in Florida, Havana and at the Panama Canal in abating the transmission of yellow fever and malaria by controlling the mosquitoes that carry these diseases, for which he used the discoveries made by the Cuban doctor Carlos J. Finlay. At first, Finlay's strategy was greeted with considerable skepticism and opposition to such hygiene measures. However, the measures Gorgas put into practice as the head of the Panama Canal Zone Sanitation Commission saved thousands of lives and contributed to the success of the canal's construction.

The idea of the Panama Canal dates back to 1513, when the Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa first crossed the Isthmus of Panama. European powers soon noticed the possibility to dig a water passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans across this narrow land bridge between North and South America. A number of proposals for a ship canal across Central America were made between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, with the chief rival to Panama being a canal through Nicaragua.

Mosquito control manages the population of mosquitoes to reduce their damage to human health, economies, and enjoyment. Mosquito control is a vital public-health practice throughout the world and especially in the tropics because mosquitoes spread many diseases, such as malaria and the Zika virus.

Gorgas Hospital was a U.S. Army hospital in Panama City, Panama, named for Army Surgeon General William C. Gorgas (1854—1920).

The history of malaria extends from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent except Antarctica. Its prevention and treatment have been targeted in science and medicine for hundreds of years. Since the discovery of the Plasmodium parasites which cause it, research attention has focused on their biology as well as that of the mosquitoes which transmit the parasites.

The Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud is a medical research institution that has been dedicated for more than 80 years on investigating diseases in the tropics and preventive medicine. Established in 1921, GMI had its building inaugurated in Panama City in 1928. It was administered by the United States until 1990. Since 1990, it has been a part of the Ministry of Health of the Government of Panama.

The Isthmian Canal Commission was an American administration commission set up to oversee the construction of the Panama Canal in the early years of American involvement. Established on February 26, 1904, it was given control of the Panama Canal Zone over which the United States exercised sovereignty. The commission reported directly to Secretary of War William Taft.

John Findley Wallace was an American engineer and administrator, best known for serving as chief engineer for construction of the Panama Canal between 1904 and 1905. He had previously gained experience in railroad construction in the American Midwest.

Mosquito-borne diseases or mosquito-borne illnesses are diseases caused by bacteria, viruses or parasites transmitted by mosquitoes. Nearly 700 million people contract mosquito-borne illnesses each year, resulting in more than a million deaths.

Stanley Jennings Carpenter, Colonel, U.S. Army, retired, deceased, a noted medical entomologist, was born December 9, 1904, in West Liberty, Morgan County, Kentucky, and died on August 28, 1984, at Santa Rosa, California at age 79. This biographical sketch is based on the text of a memorial lecture presented by a colleague on March 24, 1997.

Alexander Jeremiah Orenstein was a Russian-born naturalized American general and military doctor.

Henry Rose Carter was an American physician, epidemiologist, and public health official who served as assistant surgeon general of the Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. His research and protocols were critical in understanding and preventing the transmission of both malaria and yellow fever.