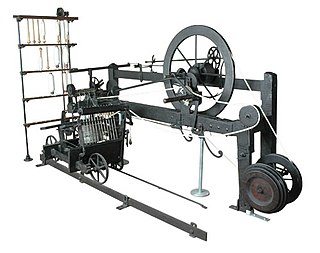

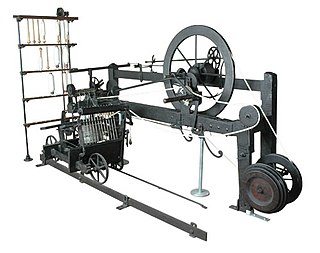

The Industrial Revolution, also known as the First Industrial Revolution, was a period of global transition of the human economy towards more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes that succeeded the Agricultural Revolution, starting from Great Britain and spreading to continental Europe and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going from hand production methods to machines; new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes; the increasing use of water power and steam power; the development of machine tools; and the rise of the mechanized factory system. Output greatly increased, and the result was an unprecedented rise in population and the rate of population growth. The textile industry was the first to use modern production methods, and textiles became the dominant industry in terms of employment, value of output, and capital invested.

Spinning is a twisting technique to form yarn from fibers. The fiber intended is drawn out, twisted, and wound onto a bobbin. A few popular fibers that are spun into yarn other than cotton, which is the most popular, are viscose, animal fibers such as wool, and synthetic polyester. Originally done by hand using a spindle whorl, starting in the 500s AD the spinning wheel became the predominant spinning tool across Asia and Europe. The spinning jenny and spinning mule, invented in the late 1700s, made mechanical spinning far more efficient than spinning by hand, and especially made cotton manufacturing one of the most important industries of the Industrial Revolution.

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus Gossypium in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor percentages of waxes, fats, pectins, and water. Under natural conditions, the cotton bolls will increase the dispersal of the seeds.

A spinning wheel is a device for spinning thread or yarn from fibres. It was fundamental to the cotton textile industry prior to the Industrial Revolution. It laid the foundations for later machinery such as the spinning jenny and spinning frame, which displaced the spinning wheel during the Industrial Revolution.

This aims to be a complete article list of economics topics:

Jute is a long, rough, shiny bast fiber that can be spun into coarse, strong threads. It is produced from flowering plants in the genus Corchorus, of the mallow family Malvaceae. The primary source of the fiber is Corchorus olitorius, but such fiber is considered inferior to that derived from Corchorus capsularis.

The Industrial Age is a period of history that encompasses the changes in economic and social organization that began around 1760 in Great Britain and later in other countries, characterized chiefly by the replacement of hand tools with power-driven machines such as the power loom and the steam engine, and by the concentration of industry in large establishments.

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a plant in the botanical class of Cannabis sativa cultivars grown specifically for industrial and consumable use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants on Earth. It was also one of the first plants to be spun into usable fiber 50,000 years ago. It can be refined into a variety of commercial items, including paper, rope, textiles, clothing, biodegradable plastics, paint, insulation, biofuel, food, and animal feed.

Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution was centred in south Lancashire and the towns on both sides of the Pennines in the United Kingdom. The main drivers of the Industrial Revolution were textile manufacturing, iron founding, steam power, oil drilling, the discovery of electricity and its many industrial applications, the telegraph and many others. Railroads, steamboats, the telegraph and other innovations massively increased worker productivity and raised standards of living by greatly reducing time spent during travel, transportation and communications.

A plantation economy is an economy based on agricultural mass production, usually of a few commodity crops, grown on large farms worked by laborers or slaves. The properties are called plantations. Plantation economies rely on the export of cash crops as a source of income. Prominent crops included Red Sandalwood, cotton, rubber, sugar cane, tobacco, figs, rice, kapok, sisal, and species in the genus Indigofera, used to produce indigo dye.

The textile industry is primarily concerned with the design, production and distribution of textiles: yarn, cloth and clothing. The raw material may be natural, or synthetic using products of the chemical industry.

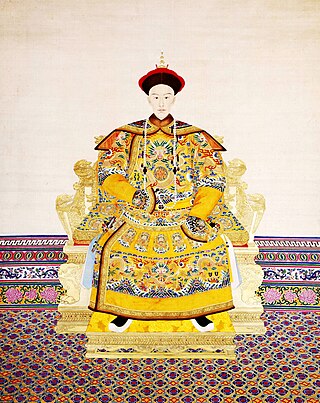

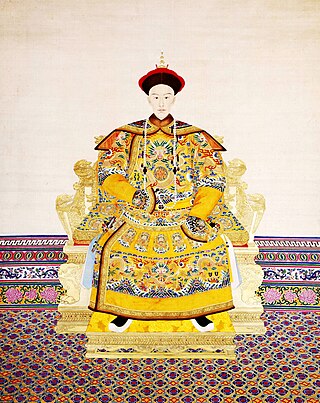

The Great Divergence or European miracle is the socioeconomic shift in which the Western world overcame pre-modern growth constraints and emerged during the 19th century as the most powerful and wealthy world civilizations, eclipsing previously dominant or comparable civilizations from the Middle East and Asia such as Qing China, Mughal India, the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Iran, and Tokugawa Japan, among others.

John Mark Dutton Elvin was an Australian academic. A professor emeritus of Chinese history at Australian National University, he specialised in the late imperial period. He was also emeritus fellow of St Antony's College, Oxford.

During the Manchu–led Qing dynasty, the economy was significantly developed and markets continued to expand especially in the High Qing era, and imperial China experienced a second commercial revolution in the economic history of China from the mid-16th century to the end of the 18th century. But akin to the other major non-European powers around the world at that time like the Islamic gunpowder empires and Tokugawa Japan, such an economy development did not keep pace with the economies of European countries in the Industrial Revolution occurring by the early 19th century, which resulted in a dramatic change described by the 19th-century Qing official Li Hongzhang as "the biggest change in more than three thousand years" (三千年未有之大變局).

The productivity-improving technologies are the technological innovations that have historically increased productivity.

The history of cotton can be traced to domestication for an important role in the history of India, the British Empire, and the United States, and continues to be an important crop and commodity.

The textile industry in India traditionally, after agriculture, is the only industry that has generated huge employment for both skilled and unskilled labour. The textile industry continues to be the second-largest employment generating sector in India. It offers direct employment to over 35 million people in the country. India is the world's second largest exporter of textiles and clothing, and in the fiscal year 2022, the exports stood at US$ 44.4 billion. According to the Ministry of Textiles, the share of textiles in total exports during April–July 2010 was 11.04%. During 2009–2010, the Indian textile industry was pegged at US$55 billion, 64% of which services domestic demand. In 2010, there were 2,500 textile weaving factories and 4,135 textile finishing factories in all of India. According to AT Kearney’s ‘Retail Apparel Index’, India was ranked as the fourth most promising market for apparel retailers in 2009.

In the United States from the late 18th and 19th centuries, the Industrial Revolution affected the U.S. economy, progressing it from manual labor, farm labor and handicraft work, to a greater degree of industrialization based on wage labor. There were many improvements in technology and manufacturing fundamentals with results that greatly improved overall production and economic growth in the U.S.

The textile industry in China is the largest in the world in both overall production and exports. China exported $274 billion in textiles in 2013, a volume that was nearly seven times that of Bangladesh, the second largest exporter with $40 billion in exports. This accounted for 43.1% of global clothing exports. According to Women's Wear Daily, they account for more than 50 percent of the world's total overall production, exports, and retail. As of 2022, their textile and garment exports total up to around $316 billion and their retail up to $672 billion. China has been ranked as the world's largest manufacturer since 2010.

Hemp paper is paper varieties consisting exclusively or to a large extent from pulp obtained from fibers of industrial hemp. The products are mainly specialty papers such as cigarette paper, banknotes and technical filter papers. Compared to wood pulp, hemp pulp offers a four to five times longer fibre, a significantly lower lignin fraction as well as a higher tear resistance and tensile strength. Because the paper industry's processes have been optimized for wood as the feedstock, production costs currently are much higher than for paper from wood.