History

The nature of scientific revolutions has been studied by modern philosophy since Immanuel Kant used the phrase in the preface to the second edition of his Critique of Pure Reason (1787). Kant used the phrase "revolution of the way of thinking" (Revolution der Denkart) to refer to Greek mathematics and Newtonian physics. In the 20th century, new developments in the basic concepts of mathematics, physics, and biology revitalized interest in the question among scholars.

Original usage

In his 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions , Kuhn explains the development of paradigm shifts in science into four stages:

- Normal science – In this stage, which Kuhn sees as most prominent in science, a dominant paradigm is active. This paradigm is characterized by a set of theories and ideas that define what is possible and rational to do, giving scientists a clear set of tools to approach certain problems. Some examples of dominant paradigms that Kuhn gives are: Newtonian physics, caloric theory, and the theory of electromagnetism. [5] Insofar as paradigms are useful, they expand both the scope and the tools with which scientists do research. Kuhn, in discussion of theory-ladenness, stresses that, rather than being monolithic, the paradigms that define normal science can be particular to different people. [6] [4] A chemist and a physicist might operate with different paradigms of what a helium atom is. [7] Under normal science, scientists encounter anomalies that cannot be explained by the universally accepted paradigm within which scientific progress has thereto been made.

- Extraordinary research – When enough significant anomalies have accrued against a current paradigm, the scientific discipline is thrown into a state of crisis. To address the crisis, scientists push the boundaries of normal science in what Kuhn calls “extraordinary research”, which is characterized by its exploratory nature. [8] Without the structures of the dominant paradigm to depend on, scientists engaging in extraordinary research must produce new theories, thought experiments, and experiments to explain the anomalies. Kuhn sees the practice of this stage – “the proliferation of competing articulations, the willingness to try anything, the expression of explicit discontent, the recourse to philosophy and to debate over fundamentals” – as even more important to science than paradigm shifts. [9]

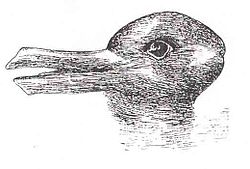

- Adoption of a new paradigm – Eventually a new paradigm is formed, which gains its own new followers. For Kuhn, this stage entails both resistance to the new paradigm, and reasons for why individual scientists adopt it. According to Max Planck, "a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it." [10] Because scientists are committed to the dominant paradigm, and paradigm shifts involve gestalt-like changes, Kuhn stresses that paradigms are difficult to change. However, paradigms can gain influence by explaining or predicting phenomena much better than before (i.e., Bohr's model of the atom) or by being more subjectively pleasing. During this phase, proponents for competing paradigms address what Kuhn considers the core of a paradigm debate: whether a given paradigm will be a good guide for future problems – things that neither the proposed paradigm nor the dominant paradigm are capable of solving currently. [11]

- Aftermath of the scientific revolution – In the long run, the new paradigm becomes institutionalized as the dominant one. Textbooks are written, obscuring the revolutionary process.