| History of Scotland |

|---|

|

The historiography of Scotland refers to the sources, critical methods and interpretive models used by scholars to come to an understanding of the history of Scotland.

| History of Scotland |

|---|

|

The historiography of Scotland refers to the sources, critical methods and interpretive models used by scholars to come to an understanding of the history of Scotland.

Scottish historiography begins with Chronicles of the Picts and Scots, many of them written by monks in Latin. The first to adopt a critical approach to organising this material was also a monk, Andrew of Wyntoun in the 14th century. His clerical connections gave him access to sources in monasteries across Scotland, England and beyond, and his educated background perhaps fuelled his critical spirit. Nevertheless, he wrote his chronicle in a poetic format and at the behest of patrons. He begins his tale with the creation of angels. Nevertheless, his later volumes (closer to his own time) are still a prime source for modern historians. The critical spirit was taken forward by the Paris-based philosopher and historian John Mair, who weeded out many of the fabulous aspects of the story. Following him, the first Principal of Aberdeen University, Hector Boece further developed the evidence-based and critical approach. Bishop John Lesley, not only a scholar but, as a minister of the Scottish Crown, with unrivaled access to source materials, laid the foundations for modern historiography.

The disputes of the Reformation sharpened critical approaches on all sides, while the humanistic concern for ancient sources saw particular attention being devoted to the collection, conservation and organisation of historical evidence. George Buchanan was perhaps the greatest of the Scottish humanists. The importance of history to all sides in religious disputes led to divergence of views, but also further developed techniques of analysis during the 17th Century. This was also a time of an increasing demand by governments for data - statistical, administrative and legal - on their realms. This was another motor for systematic evidence collection and analysis. Many of the Scottish jurists - Lord Stair - contributed to the development of modern Scottish historiography.

The 18th century saw itself as the Age of Reason and in this climate of Enlightenment. Enlightenment historians tended to react with embarrassment to Scottish history, particularly the feudalism of the Middle Ages and the religious intolerance of the Reformation. [1] Seemingly measured approaches were taken both by those who maintained a distinctly religious approach - such as Principal William Robertson - "The history of Scotland, during the reigns of Queen Mary and of King James VI. (London : 1759)" - and those who sought to escape from that perspective. Among the latter, the greatest was David Hume, in whose work we can see the beginnings of modern historiography. No doubt limited by his own perspective, and by the still limited evidence available, he nonetheless set out a picture of the development of Scottish history which still convinces many today. This century was also the century which saw the beginnings of a local archaeology, though this was still regarded somewhat of a personal eccentricity. The fact that Hume's "History of Great Britain" was very quickly renamed "History of England" is indicative of a change of focus that happened follow the Treaty of Union (1707) with England. Thereafter, a particularly Scottish historiography languished - whether in a romanticised nostalgia for a lost identity, or in continuing religious polemics. Scottish History became a sub-chapter in English history. Even so great an historian as Lord McAuley wrote only a "History of England".

In contrast to the Enlightenment, many historians of the early nineteenth century rehabilitated large areas of Scottish history as suitable for serious study. [2] Lawyer and antiquarian Cosmo Innes, who produced works on Scotland in the Middle Ages (1860), and Sketches of Early Scottish History (1861), has been likened to the pioneering history of Georg Heinrich Pertz, one of the first writers to collate the major historical accounts of German history. [3] Patrick Fraser Tytler's nine-volume history of Scotland (1828–43), particularity his sympathetic view of Mary, Queen of Scots, have led to comparisons with Leopold von Ranke, considered the father of modern scientific historical writing. [3] Tytler was co-founder with Scott of the Bannatyne Society in 1823, which helped further the course of historical research in Scotland. [4] Thomas M'Crie's (1797–1875) biographies of John Knox and Andrew Melville, figures generally savaged in the Enlightenment, helped rehabilitate their reputations. [5] W. F. Skene's (1809–92) three part study of Celtic Scotland (1886–91) was the first serious investigation of the region and helped spawn the Scottish Celtic Revival. [5] Issues of race became important, with Pinkerton, James Sibbald (1745–1803) and John Jamieson (1758–1839) subscribing to a theory of Picto-Gothicism, which postulated a Germanic origin for the Picts and the Scots language. [6]

Among the most significant intellectual figures associated with Romanticism was Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), born in Scotland and later a resident of London. He was largely responsible for bringing the works of German Romantics such as Schiller and Goethe to the attention of a British audience. [7] An essayist and historian, he invented the phrase "hero-worship", lavishing largely uncritical praise on strong leaders such as Oliver Cromwell, Frederick the Great and Napoleon. [8] His The French Revolution: A History (1837) dramatised the plight of the French aristocracy, but stressed the inevitability of history as a force. [9] With French historian Jules Michelet, he is associated with the use of the "historical imagination". [10] In Romantic historiography this led to a tendency to emphasise sentiment and identification, inviting readers to sympathise with historical personages and even to imagine interactions with them. [11] In contrast to many continental Romantic historians, Carlyle remained largely pessimistic about human nature and events. He believed that history was a form of prophesy that could reveal patterns for the future. In the late nineteenth century he became one of a number of Victorian sage writers and social commentators. [12]

Romantic writers often reacted against the empiricism of Enlightenment historical writing, putting forward the figure of the "poet-historian" who would mediate between the sources of history and the reader, using insight to create more than chronicles of facts. For this reason, Romantic historians such as Thierry saw Walter Scott, who had spent considerable effort uncovering new documents and sources for his novels, as an authority in historical writing. [13] Scott is now seen primarily as a novelist, but also produced a nine-volume biography of Napoleon, [14] and has been described as "the towering figure of Romantic historiography in Transatlantic and European contexts", having a profound effect on how history, particularly that of Scotland, was understood and written. [15] Historians that acknowledged his influence included Chateaubriand, Macaulay, and Ranke. [16]

In the 1960s, with the expansion of Higher Education, new Universities were established and with them new departments of history, some specialising in Scottish history. This allowed new attention to be paid to the particular geographic, demographic, governmental, legal and cultural structures of Scotland and to relate these to the wider European context, as well as those of Great Britain and its Empire. The distinctiveness of Scottish historiography now lies in its object of study rather than its approaches - though no doubt earlier historians can be glimpsed looking over their shoulders to events in England.

The recorded history of Scotland begins with the arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century, when the province of Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall. North of this was Caledonia, inhabited by the Picti, whose uprisings forced Rome's legions back to Hadrian's Wall. As Rome finally withdrew from Britain, a Gaelic tribe from Ireland called the Scoti began colonising Western Scotland and Wales. Before Roman times, prehistoric Scotland entered the Neolithic Era about 4000 BC, the Bronze Age about 2000 BC, and the Iron Age around 700 BC.

The Scottish Enlightenment was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Scottish Lowlands and five universities. The Enlightenment culture was based on close readings of new books, and intense discussions which took place daily at such intellectual gathering places in Edinburgh as The Select Society and, later, The Poker Club, as well as within Scotland's ancient universities.

Scottish literature is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers. It includes works in English, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Brythonic, French, Latin, Norn or other languages written within the modern boundaries of Scotland.

The Agricultural Revolution in Scotland was a series of changes in agricultural practice that began in the 17th century and continued in the 19th century. They began with the improvement of Scottish Lowlands farmland and the beginning of a transformation of Scottish agriculture from one of the least modernised systems to what was to become the most modern and productive system in Europe. The traditional system of agriculture in Scotland generally used the runrig system of management, which had possibly originated in the Late Middle Ages. The basic pre-improvement farming unit was the baile and the fermetoun. In each, a small number of families worked open-field arable and shared grazing. Whilst run rig varied in its detail from place to place, the common defining detail was the sharing out by lot on a regular basis of individual parts ("rigs") of the arable land so that families had intermixed plots in different parts of the field.

Scotland in the early modern period refers, for the purposes of this article, to Scotland between the death of James IV in 1513 and the end of the Jacobite risings in the mid-eighteenth century. It roughly corresponds to the early modern period in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the start of the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution.

Scotland in the modern era, from the end of the Jacobite risings and beginnings of industrialisation in the 18th century to the present day, has played a major part in the economic, military and political history of the United Kingdom, British Empire and Europe, while recurring issues over the status of Scotland, its status and identity have dominated political debate.

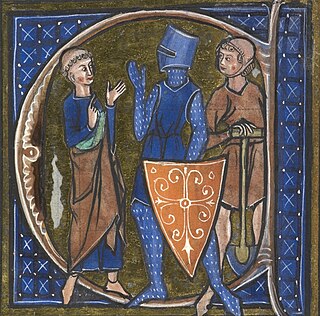

Scottish society in the Middle Ages is the social organisation of what is now Scotland between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century and the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Social structure is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources. Kinship groups probably provided the primary system of organisation and society was probably divided between a small aristocracy, whose rationale was based around warfare, a wider group of freemen, who had the right to bear arms and were represented in law codes, above a relatively large body of slaves, who may have lived beside and become clients of their owners.

The Renaissance in Scotland was a cultural, intellectual and artistic movement in Scotland, from the late fifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late fourteenth century and reaching northern Europe as a Northern Renaissance in the fifteenth century. It involved an attempt to revive the principles of the classical era, including humanism, a spirit of scholarly enquiry, scepticism, and concepts of balance and proportion. Since the twentieth century, the uniqueness and unity of the Renaissance has been challenged by historians, but significant changes in Scotland can be seen to have taken place in education, intellectual life, literature, art, architecture, music, science and politics.

Romanticism in Scotland was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that developed between the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries. It was part of the wider European Romantic movement, which was partly a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment, emphasising individual, national and emotional responses, moving beyond Renaissance and Classicist models, particularly into nostalgia for the Middle Ages. The concept of a separate national Scottish Romanticism was first articulated by the critics Ian Duncan and Murray Pittock in the Scottish Romanticism in World Literatures Conference held at UC Berkeley in 2006 and in the latter's Scottish and Irish Romanticism (2008), which argued for a national Romanticism based on the concepts of a distinct national public sphere and differentiated inflection of literary genres; the use of Scots language; the creation of a heroic national history through an Ossianic or Scottian 'taxonomy of glory' and the performance of a distinct national self in diaspora.

Architecture in early modern Scotland encompasses all building within the borders of the kingdom of Scotland, from the early sixteenth century to the mid-eighteenth century. The time period roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the start of the Enlightenment and Industrialisation.

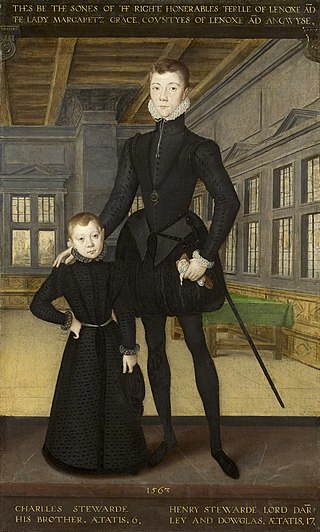

Government in early modern Scotland included all forms of administration, from the crown, through national institutions, to systems of local government and the law, between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. It roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. Monarchs of this period were the Stuarts: James IV, James V, Mary Queen of Scots, James VI, Charles I, Charles II, James VII, William III and Mary II, Anne, and the Hanoverians: George I and George II.

Women in early modern Scotland, between the Renaissance of the early sixteenth century and the beginnings of industrialisation in the mid-eighteenth century, were part of a patriarchal society, though the enforcement of this social order was not absolute in all aspects. Women retained their family surnames at marriage and did not join their husband's kin groups. In higher social ranks, marriages were often political in nature and the subject of complex negotiations in which women as matchmakers or mothers could play a major part. Women were a major part of the workforce, with many unmarried women acting as farm servants and married women playing a part in all the major agricultural tasks, particularly during harvest. Widows could be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading, but many at the bottom of society lived a marginal existence.

Education in early modern Scotland includes all forms of education within the modern borders of Scotland, between the end of the Middle Ages in the late fifteenth century and the beginnings of the Enlightenment in the mid-eighteenth century. By the sixteenth century such formal educational institutions as grammar schools, petty schools and sewing schools for girls were established in Scotland, while children of the nobility often studied under private tutors. Scotland had three universities, but the curriculum was limited and Scottish scholars had to go abroad to gain second degrees. These contacts were one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of Humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life. Humanist concern with education and Latin culminated in the Education Act 1496.

The geography of Scotland in the early modern era covers all aspects of the land in Scotland, including physical and human, between the sixteenth century and the beginnings of the Agricultural Revolution and industrialisation in the eighteenth century. The defining factor in the geography of Scotland is the distinction between the Highlands and Islands in the north and west and the Lowlands in the south and east. The Highlands were subdivided by the Great Glen and the Lowlands into the fertile Central Lowlands and the Southern Uplands. The Uplands and Highlands had a relatively short growing season, exacerbated by the Little Ice Age, which peaked towards the end of the seventeenth century.

Agriculture in Scotland in the early modern era includes all forms of farm production in the modern boundaries of Scotland, between the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-eighteenth century. This era saw the impact of the Little Ice Age, which peaked towards the end of the seventeenth century. Almost half the years in the second half of the sixteenth century saw local or national scarcity, necessitating the shipping of large quantities of grain from the Baltic Sea region. In the early seventeenth century famine was relatively common, but became rarer as the century progressed. The closing decade of the seventeenth century saw a slump, followed by four years of failed harvests, in what is known as the "seven ill years", but these shortages would be the last of their kind.

Women in Medieval Scotland includes all aspects of the lives and status of women between the departure of the Romans from North Britain in the fifth century to the introduction of the Renaissance and Reformation in the early sixteenth century. Medieval Scotland was a patriarchal society, but how exactly patriarchy worked in practice is difficult to discern. A large proportion of the women for whom biographical details survive were members of the royal houses of Scotland. Some of these became important figures. There was only one reigning Scottish Queen in this period, the uncrowned and short-lived Margaret, Maid of Norway.

Childhood in early modern Scotland includes all aspects of the lives of children, from birth to adulthood, between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. This period corresponds to the early modern period in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the beginning of industrialisation and the Enlightenment in the mid-eighteenth century.

The Royal Court of Scotland was the administrative, political and artistic centre of the Kingdom of Scotland. It emerged in the tenth century and continued until it ceased to function when James VI inherited the throne of England in 1603. For most of the medieval era, the king had no "capital" as such. The Pictish centre of Forteviot was the chief royal seat of the early Gaelic Kingdom of Alba that became the Kingdom of Scotland. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries Scone was a centre for royal business. Edinburgh only began to emerge as the capital in the reign of James III but his successors undertook occasional royal progress to a part of the kingdom. Little is known about the structure of the Scottish royal court in the period before the reign of David I when it began to take on a distinctly feudal character, with the major offices of the Steward, Chamberlain, Constable, Marischal and Lord Chancellor. By the early modern era the court consisted of leading nobles, office holders, ambassadors and supplicants who surrounded the king or queen. The Chancellor was now effectively the first minister of the kingdom and from the mid-sixteenth century he was the leading figure of the Privy Council.

The history of universities in Scotland includes the development of all universities and university colleges in Scotland, between their foundation between the fifteenth century and the present day. Until the fifteenth century, those Scots who wished to attend university had to travel to England, or to the Continent. This situation was transformed by the founding of St John's College, St Andrews in 1418 by Henry Wardlaw, bishop of St. Andrews. St Salvator's College was added to St. Andrews in 1450. The other great bishoprics followed, with the University of Glasgow being founded in 1451 and King's College, Aberdeen in 1495. Initially, these institutions were designed for the training of clerics, but they would increasingly be used by laymen. International contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life in the sixteenth century.

Scottish education in the eighteenth century concerns all forms of education, including schools, universities and informal instruction, in Scotland in the eighteenth century.