In evaluating the Gospels' historical reliability, scholars consider authorship and date of composition, [19] intention and genre, [17] gospel sources and oral tradition, [20] [21] textual criticism, and the historical authenticity of sayings and narrative events. [19]

Scope and genre

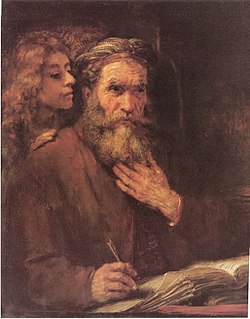

"Gospels" is the standard term for the four New Testament books carrying the names of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, each recounting the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth (including his dealings with John the Baptist, his trial and execution, the discovery of his empty tomb, and, at least in three of them, his appearances to his disciples after his death).

The genre of the gospels is essential in understanding the authors' intentions regarding the texts' historical value. New Testament scholar Graham Stanton writes, "the gospels are now widely considered to be a sub-set of the broad ancient literary genre of biographies." [24] Charles H. Talbert agrees that the gospels should be grouped with the Graeco-Roman biographies, but adds that such biographies included an element of mythology, and that the synoptic gospels do too. [25] M. David Litwa argues that the gospels belonged to the genre of "mythic historiography", where miracles and other fantastical elements were narrated in less sensationalist ways and the events were considered to have actually occurred by the readers of the time. [26] Craig S. Keener argues that the gospels are ancient biographies whose authors, like other ancient biographers at the time, were concerned with describing accurately the life and ministry of Jesus. [27] The same genre as Plutarch's Life of Alexander and Life of Caesar, which were typically ancient biographies written shortly after the death of the subject and included substantial history. [14] Although the biographical nature of the gospels has been challenged by some because of their agendas to glorify Jesus and theological interests, [15] [28] such features are expected, given that all biographies feature ideological coloring, with works by Suetonius and Plutarch serving moralizing purposes. [29] 20th century form critics such as Rudolf Bultmann and Leiva-Merikakis viewed the gospels as unique, sui generis phenomena, but today the dominant scholarly view understands the gospels as examples of ancient biography. [31]

Scholars agree Luke-Acts applied the methods of Hellenistic historiography to write some form of history. [32] [33] [34] Attitudes towards the historicity of Acts have ranged widely across scholarship in different countries. [34] [36] Regardless, EP Sanders claimed that the sources for Jesus are superior to the ones for Alexander the Great. [37]

Jeffrey Tripp observes a scholarly trend advocating for the reliability of memory and the oral gospel traditions. [38]

New Testament scholar James D.G. Dunn believed that "the earliest tradents within the Christian churches [were] preservers more than innovators...seeking to transmit, retell, explain, interpret, elaborate, but not create de novo...Through the main body of the Synoptic tradition, I believe, we have in most cases direct access to the teaching and ministry of Jesus as it was remembered from the beginning of the transmission process (which often predates Easter) and so fairly direct access to the ministry and teaching of Jesus through the eyes and ears of those who went about with him." [39] Anthony Le Donne, a leading memory researcher in Jesus studies, elaborated on Dunn's thesis, basing "his historiography squarely on Dunn's thesis that the historical Jesus is the memory of Jesus recalled by the earliest disciples". [40] According to Le Donne as explained by his reviewer, Benjamin Simpson, memories are fractured, and not exact recalls of the past. Le Donne further argues that the remembrance of events is facilitated by relating it to a common story, or "type". This means the Jesus-tradition is not a theological invention of the early Church, but rather a tradition shaped and refracted through such memory "type". Le Donne too supports a conservative view on typology compared to some other scholars, transmissions involving eyewitnesses, and ultimately a stable tradition resulting in little invention in the Gospels. [40] Le Donne expressed himself thusly vis-a-vis more skeptical scholars, "He (Dale Allison) does not read the gospels as fiction, but even if these early stories derive from memory, memory can be frail and often misleading. While I do not share Allison's point of departure (i.e. I am more optimistic), I am compelled by the method that came from it." [41]

Dale Allison emphasizes the weakness of human memory, referring to its 'many sins' and how it frequently misguides people. He expresses skepticism at other scholars' endeavors to identify authentic sayings of Jesus. Instead of isolating and authenticating individual pericopae, Allison advocates for a methodology focused on identifying patterns and finding what he calls 'recurrent attestation'. Allison argues that the general impressions left by the Gospels should be trusted, though he is more skeptical on the details; if they are broadly unreliable, then our sources almost certainly cannot have preserved any of the particulars. Opposing preceding approaches where the Gospels are historically questionable and must be rigorously sifted through by competent scholars for nuggets of information, Allison argues that the Gospels are generally accurate and often 'got Jesus right'. Dale Allison finds apocalypticism to be recurrently attested, among various other themes. [42] Reviewing his work, Rafael Rodriguez largely agrees with Allison's methodology and conclusions while arguing that Allison's discussion on memory is too one-sided, noting that memory "is nevertheless sufficiently stable to authentically bring the past to bear on the present" and that people are beholden to memory's successes in everyday life. [43]

According to Bruce Chilton and Craig Evans, "...the Judaism of the period treated such traditions very carefully, and the New Testament writers in numerous passages applied to apostolic traditions the same technical terminology found elsewhere in Judaism [...] In this way they both identified their traditions as 'holy word' and showed their concern for a careful and ordered transmission of it." [44] David Jenkins, a former Anglican Bishop of Durham and university professor, has said, "Certainly not! There is absolutely no certainty in the New Testament about anything of importance." [45]

Chris Keith has called for the employment of social memory theory regarding the memories transmitted by the Gospels over the traditional form-critical approach emphasizing a distinction between 'authentic' and 'inauthentic' tradition. Keith observes that the memories presented by the Gospels can contradict and are not always historically correct. Chris Keith argues that the Historical Jesus was the one who could create these memories, both true or not. For instance, Mark and Luke disagree on how Jesus came back to the synagogue, with the likely more accurate Mark arguing he was rejected for being an artisan, while Luke portrays Jesus as literate and his refusal to heal in Nazareth as cause of his dismissal. Keith does not view Luke's account as a fabrication since different eyewitnesses would have perceived and remembered differently. [46]

While believing that the study of the process of conversion from memories of Jesus into the Gospel tradition are too complicated for more simplistic a priori arguments the Gospels are reliable, [47] Alan Kirk criticizes allegations of memory distortion common in Biblical studies. Kirk finds that much research in psychology involves experimentation in labs decontextualized from the real world, making use of their results dubious, hence the rise of what he calls 'ecological' approaches to memory. Kirk claims that social contagion is one phenomenon that is greatly lessened or even ruled out by new study. Kirk claims that there is also an imprudent reliance on a binary distinction between exact information and later interpretation in research. [48] Kirk argues that the demise of form criticism means that the Gospels can no longer be automatically considered unreliable and that skeptics must now find new options, such as the aforementioned efforts at using evidence of memory distortion. [47] Reviewing Kirk's essay "Cognition, Commemoration, and Tradition: Memory and the Historiography of Jesus Research" (2010), biblical scholar Judith Redman provides a reflection based on her view of memory research:

They [The Gospels] are not ordinary historical accounts and cannot be treated as though they are, but nor are they simply ahistorical materials designed to convince the reader of the author's particular theological perspective. That we have increasing scientific evidence of this has important implications for Christians, but does not, I think, invalidate the preceding two millennia of faith. [49]

Alongside his work defining the Gospels as ancient biography, Craig Keener, drawing on the works of previous studies by Dunn, Kirk, Kenneth Bailey, and Robert McIver, among many others, utilizes memory theory and oral tradition to argue that the Gospels are in many ways historically accurate. [50] His work has been endorsed by Richard Bauckham, Markus Bockmuehl, and David Aune, among others. [50]

Criteria

Critical scholars have developed a number of criteria to evaluate the probability or historical authenticity of an attested event or saying in the gospels. These criteria are the criterion of dissimilarity; the criterion of embarrassment; the criterion of multiple attestation; the criterion of cultural and historical congruency; and the criterion of "Aramaisms". They are applied to the sayings and events described in the Gospels to evaluate their historical reliability.

The criterion of dissimilarity argues that if a saying or action is dissimilar or contrary to the views of Judaism in the context of Jesus or the views of the early church, then it can more confidently be regarded as an authentic saying or action of Jesus. [51] [52] Commonly cited examples of this are Jesus's controversial reinterpretation of Mosaic law in his Sermon on the Mount and Peter's decision to allow uncircumcised gentiles into what was at the time a sect of Judaism.

The criterion of embarrassment holds that the authors of the gospels had no reason to invent embarrassing incidents such as Peter's denial of Jesus or the fleeing of Jesus's followers after his arrest, and therefore such details would likely not have been included unless they were true. Bart Ehrman, using the criterion of dissimilarity to judge the historical reliability of the claim that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, writes, "it is hard to imagine a Christian inventing the story of Jesus' baptism since this could be taken to mean that he was John's subordinate." [54]

The criterion of multiple attestation says that when two or more independent sources present similar or consistent accounts, it is more likely that the accounts are accurate reports of events or that they are reporting a tradition that predates the sources. [55]

The criterion of cultural and historical congruency says that a source is less credible if the account contradicts known historical facts, or if it conflicts with cultural practices common in the period in question. [56]

The criterion of "Aramaisms" [57] is that if a saying of Jesus has Aramaic roots, reflecting his Palestinian cultural context, it is more likely to be authentic than a saying that lacks Aramaic roots. [58]