The Gospel of Luke tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke–Acts, accounting for 27.5% of the New Testament. The combined work divides the history of first-century Christianity into three stages, with the gospel making up the first two of these – the life of Jesus the Messiah from his birth to the beginning of his mission in the meeting with John the Baptist, followed by his ministry with events such as the Sermon on the Plain and its Beatitudes, and his Passion, death, and resurrection.

Gospel originally meant the Christian message, but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was reported. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words and deeds of Jesus, culminating in his trial and death and concluding with various reports of his post-resurrection appearances.

The first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus provides external information on some people and events found in the New Testament. The extant manuscripts of Josephus' book Antiquities of the Jews, written around AD 93–94, contain two references to Jesus of Nazareth and one reference to John the Baptist.

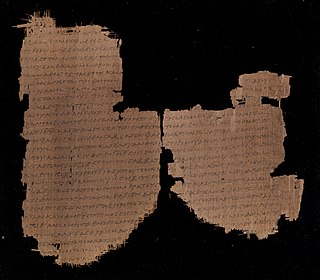

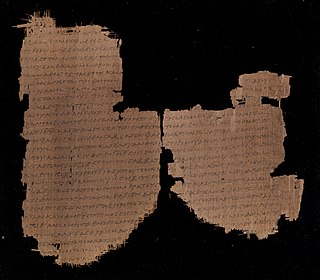

The Gospel of Thomas is an extra-canonical sayings gospel. It was discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in 1945 among a group of books known as the Nag Hammadi library. Scholars speculate the works were buried in response to a letter from Bishop Athanasius declaring a strict canon of Christian scripture. Scholars have proposed dates of composition as early as 60 AD and late as 250 AD, with most placing it during the second century. Many scholars have seen it as evidence of the existence of a "Q source" that might have been similar in its form as a collection of sayings of Jesus, without any accounts of his deeds or his life and death, referred to as a sayings gospel, though most conclude that Thomas depends on or harmonizes the Synoptics.

The Jesus Seminar was a group of about 50 biblical criticism scholars and 100 laymen founded in 1985 by Robert Funk that originated under the auspices of the Westar Institute. The seminar was very active through the 1980s and 1990s, and into the early 21st century.

The historicity of Jesus is the question of whether Jesus historically existed. The question of historicity was generally settled in scholarship in the early 20th century. Today scholars agree that a Jewish man named Jesus of Nazareth did exist in the Herodian Kingdom of Judea and the subsequent Herodian tetrarchy in the 1st century AD, upon whose life and teachings Christianity was later constructed, but a distinction is made by scholars between 'the Jesus of history' and 'the Christ of faith'.

The term "historical Jesus" refers to the life and teachings of Jesus as interpreted through critical historical methods, in contrast to what are traditionally religious interpretations. It also considers the historical and cultural contexts in which Jesus lived. Virtually all scholars of antiquity accept that Jesus was a historical figure, and the idea that Jesus was a mythical figure has been consistently rejected by the scholarly consensus as a fringe theory. Scholars differ about the beliefs and teachings of Jesus as well as the accuracy of the biblical accounts, with only two events being supported by nearly universal scholarly consensus: Jesus was baptized and Jesus was crucified.

Most scholars who study the historical Jesus and early Christianity believe that the canonical gospels and the life of Jesus must be viewed within their historical and cultural context, rather than purely in terms of Christian orthodoxy. They look at Second Temple Judaism, the tensions, trends, and changes in the region under the influence of Hellenism and the Roman occupation, and the Jewish factions of the time, seeing Jesus as a Jew in this environment; and the written New Testament as arising from a period of oral gospel traditions after his death.

Jesus, also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the central figure of Christianity, the world's largest religion. Most Christians believe Jesus to be the incarnation of God the Son and the awaited messiah, or Christ, a descendant from the Davidic line that is prophesied in the Old Testament.

The quest for the historical Jesus consists of academic efforts to determine what words and actions, if any, may be attributed to Jesus, and to use the findings to provide portraits of the historical Jesus. Since the 18th century, three scholarly quests for the historical Jesus have taken place, each with distinct characteristics and based on different research criteria, which were often developed during each specific phase. These quests are distinguished from earlier approaches because they rely on the historical method to study biblical narratives. While textual analysis of biblical sources had taken place for centuries, these quests introduced new methods and specific techniques to establish the historical validity of their conclusions.

The Christ myth theory, also known as the Jesus myth theory, Jesus mythicism, or the Jesus ahistoricity theory, is the view that the story of Jesus is a work of mythology with no historical substance. Alternatively, in terms given by Bart Ehrman paraphrasing Earl Doherty, it is the view that "the historical Jesus did not exist. Or if he did, he had virtually nothing to do with the founding of Christianity."

The criterion of embarrassment is a type of biblical historical analysis in which a historical account is deemed likely to be true if the author would have no reason to invent a historical account which might embarrass them. Certain Biblical scholars have used this as a metric for assessing whether the New Testament's accounts of Jesus' actions and words are historically probable.

Ernst Käsemann was a German Lutheran theologian and professor of New Testament in Mainz (1946–1951), Göttingen (1951–1959) and Tübingen (1959–1971).

John Paul Meier was an American biblical scholar and Catholic priest. He was author of the series A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, six other books, and more than 70 articles for peer-reviewed or solicited journals or books.

The criterion of multiple attestation, also called the criterion of independent attestation or the cross-section method, is a tool used by Biblical scholars to help determine whether certain actions or sayings by Jesus in the New Testament are from the Historical Jesus. Simply put, the more independent witnesses that report an event or saying, the better. This criterion was first developed by F. C. Burkitt in 1906, at the end of the first quest for the historical Jesus.

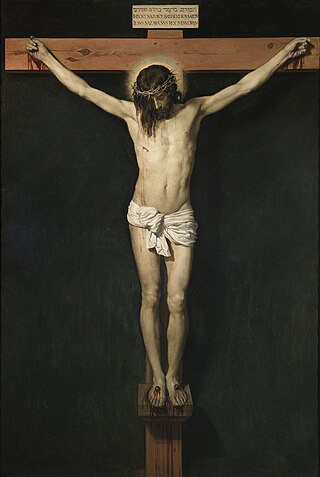

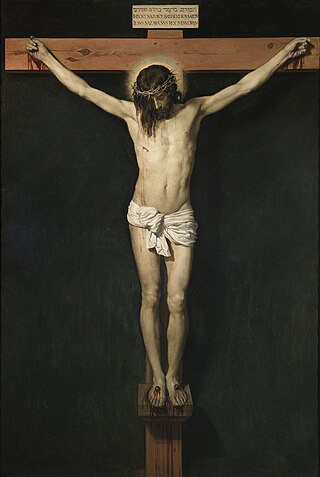

The crucifixion of Jesus was the violent death of Jesus by nailing him to a wooden cross. It occurred in 1st-century Rome's Judaea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, later attested to by other ancient sources, and is broadly accepted as one of the events to have most likely occurred during his life. There is no consensus among historians on the details.

The historical reliability of the Gospels is evaluated by experts who have not reached complete consensus. While all four canonical gospels contain some sayings and events that may meet at least one of the five criteria for historical reliability used in biblical studies, the assessment and evaluation of these elements is a matter of ongoing debate.

Christian sources such as the New Testament books in the Christian Bible, include detailed accounts about Jesus, but scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the biblical accounts of Jesus. The only two events subject to "almost universal assent" are that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist and was crucified by the order of the Roman Prefect Pontius Pilate.

Scholars have given various interpretations of the elements of the Gospel stories.

The criterion of contextual credibility, also variously called the criterion of Semitisms and Palestinian background or the criterion of Semitic language phenomena and Palestinian environment, is a tool used by Biblical scholars to help determine whether certain actions or sayings by Jesus in the New Testament are from the Historical Jesus. Simply put, if a tradition about Jesus does not fit the linguistic, cultural, historical and social environment of Jewish Aramaic-speaking 1st-century Palestine, it is probably not authentic. The linguistic and the environmental criteria are treated separately by some scholars, but taken together by others.