The Free Church of Scotland is a Scottish denomination which was formed in 1843 by a large withdrawal from the established Church of Scotland in a schism known as the Disruption of 1843. In 1900, the vast majority of the Free Church of Scotland joined with the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland to form the United Free Church of Scotland. In 1904, the House of Lords judged that the constitutional minority that did not enter the 1900 union were entitled to the whole of the church's patrimony ; the residual Free Church of Scotland acquiesced in the division of those assets, between itself and those who had entered the union, by a Royal Commission in 1905. Despite the late founding date, Free Church of Scotland leadership claims an unbroken succession of leaders going back to the Apostles.

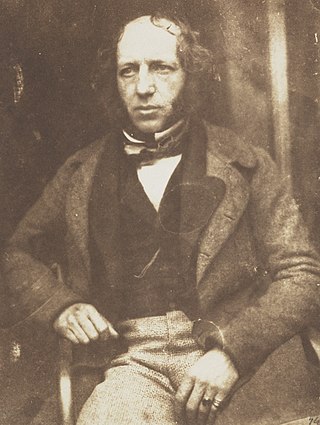

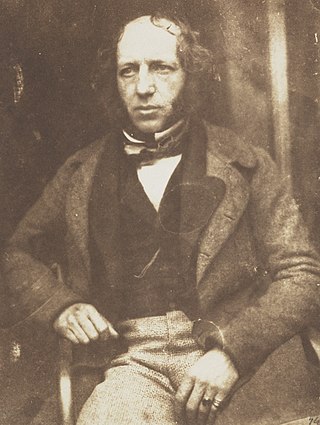

Robert Smith Candlish was a Scottish minister who was a leading figure in the Disruption of 1843. He served for many years in both St. George's Church and St George's Free Church on Charlotte Square in Edinburgh's New Town.

The Church of Scotland Act 1921 is an Act of the British Parliament. The purpose of the Act was to settle centuries of dispute between the British Parliament and the Church of Scotland over the Church's independence in spiritual matters. The passing of the Act saw the British Parliament recognise the Church's independence in spiritual matters, by giving legal recognition to the Articles Declaratory.

David Welsh FRSE was a Scottish Presbyterian minister and academic. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1842. In the Disruption of 1843 he was one of the leading figures in the establishment of the Free Church of Scotland.

Abbeygreen Church is a congregation of the Free Church of Scotland in the small town of Lesmahagow, Lanarkshire. As a Christian congregation, it is presbyterian and reformed; holding the Word of God, the Holy Bible, as the supreme rule of life and doctrine and the Westminster Confession of Faith as a sub-ordinate standard, which helps explain the doctrines of the Christian faith. Being Presbyterian, it serves as part of the Free Church of Scotland Presbytery of Glasgow and seeks to faithfully serve God in Lesmahagow and the surrounding area. Having a missional outlook it is involved with a number of missionary organizations including, but not only, UFM Worldwide and Rose of Sharon Ministries, and helps with the organization and support of the Scottish Reformed Conference.

Robert Gordon FRSE was a Scottish minister and author. Originally prominent in the Church of Scotland, and serving as Moderator of the General Assembly in 1841, following the Disruption of 1843 he joined the Free Church of Scotland and became a prominent figure in that church.

Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop was a Scottish church advocate and Liberal Party politician. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Greenock from 1852 to 1868. He was a very influential figure in the Disruption of 1843 which led to the formation of the Free Church of Scotland. For that denomination he drafted the Church-State papers: the Claim of Right and the Protest. He became known by the nickname the Member for Scotland.

Sir Henry Wellwood-Moncreiff, 10th Baronet, originally Henry Moncrieff was a Scottish minister, considered one of the most influential figures in the Free Church of Scotland in his time. Henry Wellwood Moncreiff, tenth baronet, born in 1809, was ordained minister of the parish of East Kilbride, Lanarkshire, in 1836, and at the disruption, in 1843, he joined the Free Church. He was afterwards translated to St. Cuthbert's, Edinburgh. He married in 1838, Alexina-Mary, daughter of Edinburgh surgeon George Bell. He is one of the two principal clerks of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, Patrick Clason, being the other; and on the death, in 1861, of James Robertson, professor of divinity and church history in the university of Edinburgh, he was appointed his successor as secretary to her majesty's sole and only master printers in Scotland.

Thomas Brown (1811–1893) was a Scottish minister in the Free Church of Scotland who rose to its highest rank, Moderator of the General Assembly in 1890. He was a noted geologist and botanist. He wrote prolifically on the history of the Disruption of 1843.

George Cook (1772–1845) was a Scottish minister, author of religious tracts and professor of Moral Philosophy at St Andrews University. He served as Moderator of the Church of Scotland in 1825. He was the leader of the "moderate" party in the church of Scotland on the question of the Veto Act, which led to Disruption of 1843 and the formation of the Free Church by the "evangelical party.

Patrick MacFarlan was a Scottish minister who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1834 and as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland in 1845.

Robert Cunningham Graham Speirs or Spiers FRSE (1797–1847) was a 19th-century Scottish advocate and prison reformer. In later life he is largely referred to simply as Graham Speirs. He held the offices of Sheriff of Elgin and Moray from 1835 to 1840 and subsequently was Sheriff of Midlothian from 1840 until his death in 1847. He joined the Free Church at the Disruption of 1843. He was then involved in the Sites Committee trying to persuade landowners to allow the denomination to build churches and schools on their land.

Robert Buchanan (1802–1875) was a Scottish Presbyterian minister and historian who served as Moderator of the General Assembly to the Free Church of Scotland in 1860/61. He was one of the leading figures in the Disruption of 1843.

Charles John Brown (1806–1884) was a Scottish minister, who served as Moderator of the General Assembly for the Free Church of Scotland from 1872 to 1873.

Robert MacDonald (1813–1893) was a Scottish minister of the Free Church of Scotland who served as Moderator of the General Assembly in 1882/83.

William Wilson was a Scottish minister of the Free Church of Scotland who served as Moderator of the General Assembly in 1866/67.

Alexander Campbell Cameron, known as Alexander Campbell until 1844, was a British Conservative politician.

George Buchan was a civil servant who was shipwrecked on his first passage to India as a teenager. Born into an elite family, his career progressed in the Indian Civil Service rising to the rank of Chief Secretary. Following his retirement, he came home to Scotland and had a Christian conversion. After several years as an elder in the Church of Scotland, he left at the Disruption and joined the Free Church of Scotland. He was an author writing about shipwrecks, Madras and about duelling as well as about church-state relations. He also wrote about God's providence illustrated from his own biography. Buchan was also an office bearer for a number of charity organisations.

Alexander Earle Monteith trained as a lawyer in Edinburgh and became Sheriff of Fife in 1838. He is remembered as one of the Disruption Worthies - those church leaders who, at the Disruption of 1843, left to set up the Free Church of Scotland. Monteith was an active member of many commissions involved in reforming Aberdeen University, prisons and treatment of those then called lunatics for example. Monteith was also photographed by Hill & Adamson and by his second wife, Frances, who herself was an early pioneer of calotype photography and some of whose pictures ended up in an album by David Brewster.

Alexander Stewart was born at the manse in Moulin, Perthshire, on 25 September 1794. He was the son of Alexander Stewart, minister of Canongate, Edinburgh. He was educated at King's College, Aberdeen, and the University of Glasgow. He was ordained to the Chapel-of-Ease, Rothesay, on 10 February 1824 and later translated, and admitted to Cromarty on 23 September 1824. He joined the Free Church in 1843. He continued as the minister of the Free Church, Cromarty, from 1843 to 1847. He was elected to Free St George's, Edinburgh, but died before the induction, on 5 November 1847, of a fever. He was reckoned one of the most eminent preachers in the Church. Hugh Miller wrote warmly of him.