Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important centre of Celtic Christianity under Saints Aidan, Cuthbert, Eadfrith, and Eadberht of Lindisfarne. The island was originally home to a monastery, which was destroyed during the Viking invasions but re-established as a priory following the Norman Conquest of England. Other notable sites built on the island are St. Mary the Virgin parish church, Lindisfarne Castle, several lighthouses and other navigational markers, and a complex network of lime kilns. In the present day, the island is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and a hotspot for historical tourism and bird watching. As of February 2020, the island had three pubs, a hotel and a post office.

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne was an Anglo-Saxon saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in the Kingdom of Northumbria, today in north-eastern England and south-eastern Scotland. Both during his life and after his death, he became a popular medieval saint of Northern England, with a cult centred on his tomb at Durham Cathedral. Cuthbert is regarded as the patron saint of Northumbria. His feast days are 20 March and 4 September.

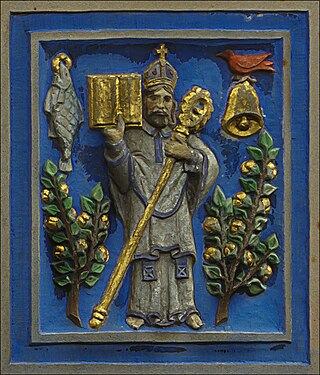

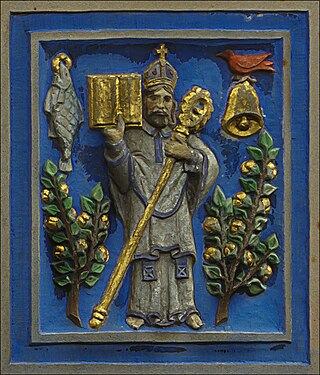

Kentigern, known as Mungo, was a missionary in the Brittonic Kingdom of Strathclyde in the late sixth century, and the founder and patron saint of the city of Glasgow.

Óengus mac Fergusa was king of the Picts from 820 until 834. In Scottish historiography, he is associated with the veneration of Saint Andrew, the patron saint of Scotland, although this has not been proven.

Aldfrith was king of Northumbria from 685 until his death. He is described by early writers such as Bede, Alcuin and Stephen of Ripon as a man of great learning. Some of his works and some letters written to him survive. His reign was relatively peaceful, marred only by disputes with Bishop Wilfrid, a major figure in the early Northumbrian church.

The Archdiocese of Glasgow was one of the thirteen dioceses of the Scottish church. It was the second largest diocese in the Kingdom of Scotland, including Clydesdale, Teviotdale, parts of Tweeddale, Liddesdale, Annandale, Nithsdale, Cunninghame, Kyle, and Strathgryfe, as well as Lennox, Carrick and the part of Galloway known as Desnes.

Finan of Lindisfarne, also known as Saint Finan, was an Irish monk, trained at Iona Abbey in Scotland, who became the second bishop of Lindisfarne from 651 until 661.

Eata, also known as Eata of Lindisfarne, was Bishop of Hexham from 678 until 681, and of then Bishop of Lindisfarne from before 681 until 685. He then was translated back to Hexham where he served until his death in 685 or 686. He was the first native of Northumbria to occupy the bishopric of Lindisfarne.

Eadfrith of Lindisfarne, also known as Saint Eadfrith, was Bishop of Lindisfarne, probably from 698 onwards. By the twelfth century it was believed that Eadfrith succeeded Eadberht and nothing in the surviving records contradicts this belief. Lindisfarne was among the main religious sites of the kingdom of Northumbria in the early eighth century, the resting place of Saints Aidan and Cuthbert. He is venerated as a Saint in the Roman Catholic Church, and in the Eastern Orthodox Church, as also in the Anglican Communion.

Christianity in medieval Scotland includes all aspects of Christianity in the modern borders of Scotland in the Middle Ages. Christianity was probably introduced to what is now Lowland Scotland by Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of Britannia. After the collapse of Roman authority in the fifth century, Christianity is presumed to have survived among the British enclaves in the south of what is now Scotland, but retreated as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced. Scotland was largely converted by Irish missions associated with figures such as St Columba, from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions founded monastic institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas. Scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity, in which abbots were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy were more relaxed and there were significant differences in practice with Roman Christianity, particularly the form of tonsure and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-seventh century. After the reconversion of Scandinavian Scotland in the tenth century, Christianity under papal authority was the dominant religion of the kingdom.

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass Scotland in the era between the death of Domnall II in 900 AD and the death of King Alexander III in 1286, which was an indirect cause of the Wars of Scottish Independence.

Scotland was divided into a series of kingdoms in the early Middle Ages, i.e. between the end of Roman authority in southern and central Britain from around 400 AD and the rise of the kingdom of Alba in 900 AD. Of these, the four most important to emerge were the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, the Britons of Alt Clut, and the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia. After the arrival of the Vikings in the late 8th century, Scandinavian rulers and colonies were established on the islands and along parts of the coasts. In the 9th century, the House of Alpin combined the lands of the Scots and Picts to form a single kingdom which constituted the basis of the Kingdom of Scotland.

The history of Christianity in Scotland includes all aspects of the Christianity in the region that is now Scotland from its introduction up to the present day. Christianity was first introduced to what is now southern Scotland during the Roman occupation of Britain, and is often said to have been spread by missionaries from Ireland in the fifth century and is much associated with St Ninian, St Kentigern and St Columba, though “they first appear in places where churches had already been established”. The Christianity that developed in Ireland and Scotland differed from that led by Rome, particularly over the method of calculating Easter, and the form of tonsure until the Celtic church accepted Roman practices in the mid-seventh century.

Billfrith is an obscure Northumbrian saint credited with providing the jewel and metalwork encrusting the former treasure binding of the Lindisfarne Gospels. His name is thought to mean "peace of the two-edge sword".

Scottish society in the Middle Ages is the social organisation of what is now Scotland between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century and the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Social structure is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources. Kinship groups probably provided the primary system of organisation and society was probably divided between a small aristocracy, whose rationale was based around warfare, a wider group of freemen, who had the right to bear arms and were represented in law codes, above a relatively large body of slaves, who may have lived beside and become clients of their owners.

The geography of Scotland in the Middle Ages covers all aspects of the land that is now Scotland, including physical and human, between the departure of the Romans in the early fifth century from what are now the southern borders of the country, to the adoption of the major aspects of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Scotland was defined by its physical geography, with its long coastline of inlets, islands and inland lochs, high proportion of land over 60 metres above sea level and heavy rainfall. It is divided between the Highlands and Islands and Lowland regions, which were subdivided by geological features including fault lines, mountains, hills, bogs and marshes. This made communications by land problematic and raised difficulties for political unification, but also for invading armies.

The Christianisation of Scotland was the process by which Christianity spread in what is now Scotland, which took place principally between the fifth and tenth centuries.

The history of popular religion in Scotland includes all forms of the formal theology and structures of institutional religion, between the earliest times of human occupation of what is now Scotland and the present day. Very little is known about religion in Scotland before the arrival of Christianity. It is generally presumed to have resembled Celtic polytheism and there is evidence of the worship of spirits and wells. The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England, from the sixth century. Elements of paganism survived into the Christian era. The earliest evidence of religious practice is heavily biased toward monastic life. Priests carried out baptisms, masses and burials, prayed for the dead and offered sermons. The church dictated moral and legal matters and impinged on other elements of everyday life through its rules on fasting, diet, the slaughter of animals and rules on purity and ritual cleansing. One of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the Cult of Saints, with shrines devoted to local and national figures, including St Andrew, and the establishment of pilgrimage routes. Scots also played a major role in the Crusades. Historians have discerned a decline of monastic life in the late medieval period. In contrast, the burghs saw the flourishing of mendicant orders of friars in the later fifteenth century. As the doctrine of Purgatory gained importance the number of chapelries, priests and masses for the dead within parish churches grew rapidly. New "international" cults of devotion connected with Jesus and the Virgin Mary began to reach Scotland in the fifteenth century. Heresy, in the form of Lollardry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early fifteenth century, but did not achieve a significant following.

This is a list of saints associated with the kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd, including Elmet, Rheged, Gododin, Manaw, Lleuddiniawn and Ystrad Clud.

Saint Munde was a Scottish abbot in Argyll, Scotland. There is some confusion between this saint and the much earlier Saint Fintan Munnu. His feast day is 15 April.