Literary hostility

20th century

Some literary figures rejected Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings outright. One member of the Inklings, Hugo Dyson, complained loudly at readings of the book; Christopher Tolkien records Dyson as "lying on the couch, and lolling and shouting and saying, 'Oh God, no more Elves.'" [22]

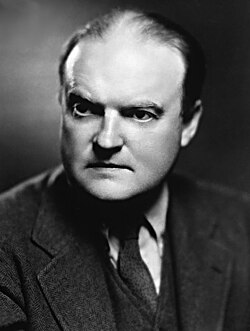

In 1956, the literary critic Edmund Wilson wrote a review entitled "Oo, Those Awful Orcs!", calling Tolkien's work "juvenile trash", and saying "Dr. Tolkien has little skill at narrative and no instinct for literary form." [21]

It was however not the case that early reviews were overwhelmingly negative. [23] An early reply to Wilson was the classicist Douglass Parker's 1957 review "Hwaet We Holbytla ..." [a] which stood up for The Lord of the Rings as a worldbuilding fantasy. Parker wrote that the "one serious attack" on the novel was "a rather nasty hatchet-job", which "appears to have resulted from Wilson's ineluctable conviction that all fantasy is trash, The Lord of the Rings is fantasy, ergo [the book was trash.]" [24] Parker argued that the book was in fact "probably the most original and varied creation ever seen in the genre, and certainly the most self-consistent; yet it is tied up with and bridged to reality as is no other fantasy." [24] He noted that the book is far from a "piddling" good-defeats-evil allegory, not least because the characters on the good side "are not abstractions, nor are they wholly good, nor are they [all] alike". [24]

In 1954, the Scottish poet Edwin Muir wrote in The Observer that "however one may look at it The Fellowship of the Ring is an extraordinary book", [25] but that although Tolkien "describes a tremendous conflict between good and evil ... his good people are consistently good, his evil figures immovably evil". [25] In 1955, Muir attacked The Return of the King , writing that "All the characters are boys masquerading as adult heroes ... and will never come to puberty ... Hardly one of them knows anything about women", causing Tolkien to complain angrily to his publisher. [26] [27]

In 1969, the feminist scholar Catherine R. Stimpson published a book-length attack on Tolkien, [28] [6] describing him as "an incorrigible nationalist", peopling his writing with "irritatingly, blandly, traditionally masculine" one-dimensional characters who live out a "bourgeois pastoral idyll". [6] This set the tone for other hostile critics. [29] Hal Colebatch [30] [31] and Patrick Curry have rebutted these charges. [6] [29]

| Stimpson's charges | Curry's rebuttals |

|---|---|

| "An incorrigible nationalist", his epic "celebrates the English bourgeois pastoral idyll. Its characters, tranquil and well fed, live best in placid, philistine, provincial rural cosiness." | "Hobbits would have liked to live quiet rural lives – if they could have". Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Merry and Pippin chose not to do so. |

| Tolkien's characters are one-dimensional, dividing neatly into "good & evil, nice & nasty" | Frodo, Gollum, Boromir, and Denethor have "inner struggles, with widely varying results". Several major characters have a shadow; Frodo has both Sam and Gollum, and Gollum is in Sam's words both "Stinker" and "Slinker". Each race (Men, Elves, Hobbits) "is a collection of good, bad, and indifferent individuals". |

| Tolkien's language betrays "class snobbery". | In The Hobbit, maybe, but not in The Lord of the Rings. Even Orcs are of three kinds, "and none are necessarily 'working-class'". Hobbits are of varied class, and the idioms of each reflect that, as with contemporary humans. Sam, "arguably the real hero", has the accent and idiom of a rural peasant; the "major villains – Smaug, Saruman, the Lord of the Nazgûl (and presumably Sauron too) are unmistakably posh". "The Scouring of the Shire" is certainly (in Tolkien's words) "the hour of the [ordinary] Shire-folk". |

| "Behind the moral structure is a regressive emotional pattern. For Tolkien is irritatingly, blandly, traditionally masculine....He makes his women characters, no matter what their rank, the most hackneyed of stereotypes. They are either beautiful and distant, simply distant, or simply simple". | "It is tempting to reply, guilty as charged", as Tolkien is paternalistic, but Galadriel is "a powerful and wise woman" and like Éowyn is "more complex and conflicted than Stimpson allows". Tolkien "committed no crime worse than being a man of his time and place". And "countless women have enjoyed and even loved The Lord of the Rings". Scholars have objected that the novel says little on women and sexuality, but they do not complain that Moby Dick says little on that subject. |

The fantasy author Michael Moorcock, in his 1978 essay, "Epic Pooh", compared Tolkien's work to Winnie-the-Pooh . He asserted, citing the third chapter of The Lord of the Rings, that its "predominant tone" was "the prose of the nursery-room ... a lullaby; it is meant to soothe and console." [32] [33]

21st century

A measure of hostility continued until the start of the 21st century. In 2001, The New York Times reviewer Judith Shulevitz criticized the "pedantry" of Tolkien's literary style, saying that he "formulated a high-minded belief in the importance of his mission as a literary preservationist, which turns out to be death to literature itself." [34] The same year, in the London Review of Books , Jenny Turner wrote that The Lord of the Rings provided "a closed space, finite and self-supporting, fixated on its own nostalgia, quietly running down"; [35] the books were suitable for "vulnerable people. You can feel secure inside them, no matter what is going on in the nasty world outside. The merest weakling can be the master of this cosy little universe. Even a silly furry little hobbit can see his dreams come true." [35] She cited the Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey's observation ("The hobbits ... have to be dug out ... of no fewer than five Homely Houses" [36] ) that the quest repeats itself, the chase in the Shire ending with dinner at Farmer Maggot's, the trouble with Old Man Willow ending with hot baths and comfort at Tom Bombadil's, and again safety after adventures in Bree, Rivendell, and Lothlórien. [35] Turner commented that reading the book is to "find oneself gently rocked between bleakness and luxury, the sublime and the cosy. Scary, safe again. Scary, safe again. Scary, safe again." [35] In her view, this compulsive rhythm is what Sigmund Freud described in his Beyond the Pleasure Principle . [35] She asked whether, in his writing, Tolkien, whose father died when he was 3 and his mother when he was 12, was not "trying to recover his lost parents, his lost childhood, an impossibly prelapsarian sense of peace?" [35]

The critic Richard Jenkyns, writing in The New Republic in 2002, criticized a perceived lack of psychological depth. Both the characters and the work itself were, according to Jenkyns, "anemic, and lacking in fiber." [37] Also that year, the science-fiction author David Brin criticised the book in Salon as carefully crafted and seductive, but backward-looking. He wrote that he had enjoyed it as a child as escapist fantasy, but that it clearly also reflected the decades of totalitarianism in the mid-20th century. Brin saw the change from feudalism to a free middle class as progress, and in his view, Tolkien, like the Romantic poets, as opposed to that. As well as its being "a great tale", Brin saw good points in the work; Tolkien was, he wrote, self-critical, for example blaming the elves for trying to halt time by forging their Rings, while the Ringwraiths could be seen as cautionary figures of Greek hubris , men who reached too high, and fell. [38] [39]

The historian Jared Lobdell, evaluating the hostile reception of Tolkien by the mainstream literary establishment in the 2006 J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia , noted that Wilson was "well known as an enemy of religion", of popular books, and "conservatism in any form". [26] Lobdell concluded that "no 'mainstream critic' appreciated The Lord of the Rings or indeed was in a position to write criticism on it – most being unsure what it was and why readers liked it." [26] He noted that Brian Aldiss was a critic of science fiction, distinguishing such "critics" from Tolkien scholarship, the study and analysis of Tolkien's themes, influences, and methods. [26]