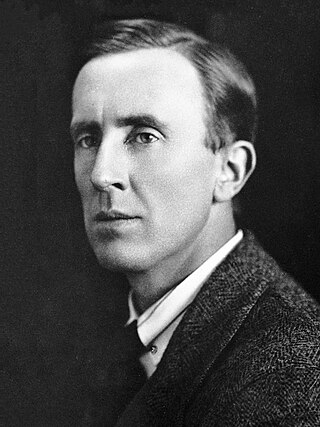

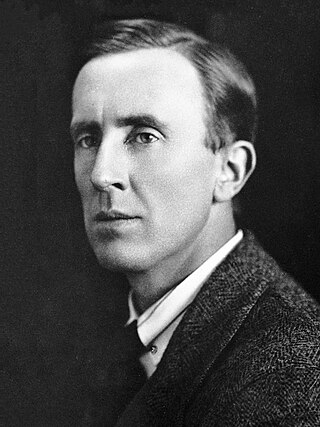

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Fingolfin is a character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, appearing in The Silmarillion. He was the son of Finwë, High King of the Noldor. He was threatened by his half-brother Fëanor, who held him in contempt for not being a pure-bred Noldor. Even so, when Fëanor stole ships and left Aman, Fingolfin chose to follow him back to Middle-earth, taking the dangerous route over the ice of the Helcaraxë. On arrival, he challenged the Dark Lord Morgoth at the gates of his fortress, Angband, but Morgoth stayed inside. When his son Fingon rescued Maedhros, son of Fëanor, Maedhros gratefully renounced his claim to kingship, and Fingolfin became High King of the Noldor. He was victorious at the battle of Dagor Aglareb, and there was peace for some 400 years until Morgoth broke out and destroyed Beleriand in the Dagor Bragollach. Fingolfin, receiving false news, rode alone to Angband and challenged Morgoth to single combat. He wounded Morgoth several times, but grew weary and was killed by the immortal Vala.

The History of Middle-earth is a 12-volume series of books published between 1983 and 1996 that collect and analyse much of Tolkien's legendarium, compiled and edited by his son, Christopher Tolkien. The series shows the development over time of Tolkien's conception of Middle-earth as a fictional place with its own peoples, languages, and history, from his earliest notions of a "mythology for England" through to the development of the stories that make up The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings. It is not a "history of Middle-earth" in the sense of being a chronicle of events in Middle-earth written from an in-universe perspective; it is instead an out-of-universe history of Tolkien's creative process. In 2000, the twelve volumes were republished in three limited edition omnibus volumes. Non-deluxe editions of the three volumes were published in 2002.

J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator is a collection of paintings and drawings by J. R. R. Tolkien for his stories, published posthumously in 1995. The book was edited by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull. It won the 1996 Mythopoeic Scholarship Award for Inklings Studies. The nature and importance of Tolkien's artwork is discussed.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the real-world history and notable fictional elements of J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy universe. It covers materials created by Tolkien; the works on his unpublished manuscripts, by his son Christopher Tolkien; and films, games and other media created by other people.

The works of J. R. R. Tolkien have served as the inspiration to painters, musicians, film-makers and writers, to such an extent that he is sometimes seen as the "father" of the entire genre of high fantasy.

Do not laugh! But once upon a time I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic to the level of romantic fairy-story... The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama. Absurd.

The works of J. R. R. Tolkien have generated a body of research covering many aspects of his fantasy writings. These encompass The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, along with his legendarium that remained unpublished until after his death, and his constructed languages, especially the Elvish languages Quenya and Sindarin. Scholars from different disciplines have examined the linguistic and literary origins of Middle-earth, and have explored many aspects of his writings from Christianity to feminism and race.

Christina Scull is a British researcher and writer best known for her books about the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, in collaboration with her husband Wayne G. Hammond who is also a Tolkien scholar. They have jointly won Mythopoeic Scholarship Awards for Inklings Studies five times.

The History of The Hobbit is a two-volume study of J. R. R. Tolkien's 1937 children's fantasy novel The Hobbit. It was first published by HarperCollins in 2007. It contains Tolkien's unpublished drafts of the novel, with commentary by John D. Rateliff. It details Tolkien's various revisions to The Hobbit, including abandoned revisions for the unpublished third edition of the work, intended for 1960, as well as previously unpublished original maps and illustrations drawn by Tolkien.

The Silmarillion is a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by Guy Gavriel Kay, who became a fantasy author. It tells of Eä, a fictional universe that includes the Blessed Realm of Valinor, the ill-fated region of Beleriand, the island of Númenor, and the continent of Middle-earth, where Tolkien's most popular works—The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—are set. After the success of The Hobbit, Tolkien's publisher, Stanley Unwin, requested a sequel, and Tolkien offered a draft of the writings that would later become The Silmarillion. Unwin rejected this proposal, calling the draft obscure and "too Celtic", so Tolkien began working on a new story that eventually became The Lord of the Rings.

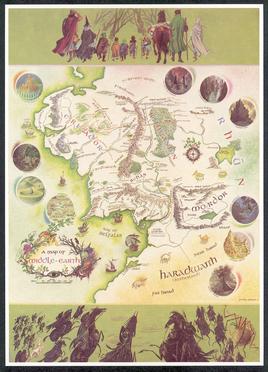

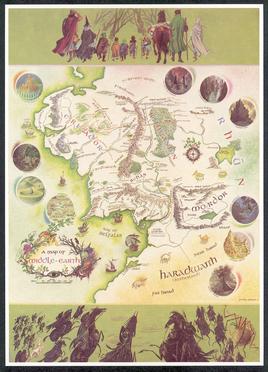

"A Map of Middle-earth" is the name of two colour posters by different artists, Barbara Remington and Pauline Baynes. They depict the north-western region of the fictional continent of Middle-earth. They were published in 1965 and 1970 by the American and British publishers of J. R. R. Tolkien's book The Lord of the Rings. The poster map by Pauline Baynes has been described as "iconic".

The plants in Middle-earth, the fictional world devised by J. R. R. Tolkien, are a mixture of real plant species with fictional ones. Middle-earth was intended to represent the real world in an imagined past, and in many respects its natural history is realistic.

J. R. R. Tolkien's maps, depicting his fictional Middle-earth and other places in his legendarium, helped him with plot development, guided the reader through his often complex stories, and contributed to the impression of depth and worldbuilding in his writings.

Tolkien's Middle-earth family trees contribute to the impression of depth and realism in the stories set in his fantasy world by showing that each character is rooted in history with a rich network of relationships. J. R. R. Tolkien included multiple family trees in both The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion; they are variously for Elves, Dwarves, Hobbits, and Men.

Tolkien's artwork was a key element of his creativity from the time when he began to write fiction. The philologist and author J. R. R. Tolkien prepared a wide variety of materials to support his fiction, including illustrations for his Middle-earth fantasy books, facsimile artefacts, more or less "picturesque" maps, calligraphy, and sketches and paintings from life. Some of his artworks combined several of these elements.

J. R. R. Tolkien invented heraldic devices for many of the characters and nations of Middle-earth. His descriptions were in simple English rather than in specific blazon. The emblems correspond in nature to their bearers, and their diversity contributes to the richly-detailed realism of his writings.

John Garth is a British journalist and author, known especially for writings about J. R. R. Tolkien including his biography Tolkien and the Great War and a book on the places that inspired Middle-earth, The Worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien. He won a 2004 Mythopoeic Award for Scholarship for his work on Tolkien. The biography influenced much Tolkien scholarship in the subsequent decades.

J. R. R. Tolkien included many elements in his Middle-earth writings, especially The Lord of the Rings, other than narrative text. These include artwork, calligraphy, chronologies, family trees, heraldry, languages, maps, poetry, proverbs, scripts, glossaries, prologues, and annotations. Scholars have stated that the use of these elements places Tolkien in the tradition of English antiquarianism.

Since the publication of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit in 1937, artists including Tolkien himself have sought to capture aspects of Middle-earth fantasy novels in paintings and drawings. He was followed in his lifetime by artists whose work he liked, such as Pauline Baynes, Mary Fairburn, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, and Ted Nasmith, and by some whose work he rejected, such as Horus Engels for the German edition of The Hobbit. Tolkien had strong views on illustration of fantasy, especially in the case of his own works. His recorded opinions range from his rejection of the use of images in his 1936 essay On Fairy-Stories, to agreeing the case for decorative images for certain purposes, and his actual creation of images to accompany the text in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Commentators including Ruth Lacon and Pieter Collier have described his views on illustration as contradictory, and his requirements as being as fastidious as his editing of his novels.

Tolkien Calendars, displaying artworks interpreting J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, have appeared annually since 1976. Some of the early calendars were illustrated with Tolkien's own artwork. Artists including the Brothers Hildebrandt and Ted Nasmith produced popular work on themes from The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit; later calendars also illustrated scenes from The Silmarillion. Some calendars have been named "Hobbit Calendar" or "Lord of the Rings Calendar", but "Tolkien Calendar" has remained the most popular choice of name.