The Lord of the Rings is an epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's book The Hobbit, but eventually developed into a much larger work. Written in stages between 1937 and 1949, The Lord of the Rings is one of the best-selling books ever written, with over 150 million copies sold.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy writings, Isengard is a large fortress in Nan Curunír, the Wizard's Vale, in the western part of Middle-earth. In the fantasy world, the name of the fortress is described as a translation of Angrenost, a word in the elvish language Sindarin, which Tolkien invented.

The Atlas of Middle-earth by Karen Wynn Fonstad is an atlas of J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional realm of Middle-earth. It was published in 1981, following Tolkien's major works The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion.

"The Scouring of the Shire" is the penultimate chapter of J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy The Lord of the Rings. The Fellowship hobbits, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin, return home to the Shire to find that it is under the brutal control of ruffians and their leader "Sharkey", revealed to be the Wizard Saruman. The ruffians have despoiled the Shire, cutting down trees and destroying old houses, as well as replacing the old mill with a larger one full of machinery which pollutes the air and the water. The hobbits rouse the Shire to rebellion, lead their fellow-hobbits to victory in the Battle of Bywater, and end Saruman's rule.

In J. R. R. Tolkien’s fictional universe of Middle-earth, the Old Forest was a daunting and ancient woodland just beyond the eastern borders of the Shire. Its first and main appearance in print was in The Fellowship of the Ring, especially in the eponymous chapter 6.

Magic in Middle-earth is the use of supernatural power in J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional Middle-earth. Tolkien distinguishes ordinary magic from witchcraft, the latter always deceptive, stating that either type could be used for good or evil.

The cosmology of J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium combines aspects of Christian theology and metaphysics with pre-modern cosmological concepts in the flat Earth paradigm, along with the modern spherical Earth view of the Solar System.

J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century is a 2000 book of literary criticism written by Tom Shippey. It is about the work of the philologist and fantasy author J. R. R. Tolkien. In it, Shippey argues for the relevance of Tolkien today and attempts to firmly establish Tolkien's literary merits, based on analysis of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion, and Tolkien's shorter works.

J. R. R. Tolkien's bestselling fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings had an initial mixed literary reception. Despite some enthusiastic early reviews from supporters such as W. H. Auden, Iris Murdoch, and C. S. Lewis, literary hostility to Tolkien quickly became acute and continued until the start of the 21st century. From 1982, Tolkien scholars such as Tom Shippey and Verlyn Flieger began to roll back the hostility, defending Tolkien, rebutting the critics' attacks and analysing what they saw as good qualities in Tolkien's writing.

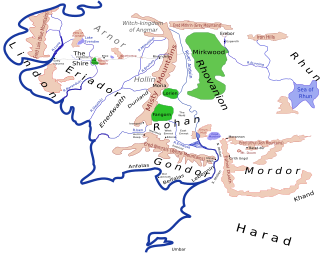

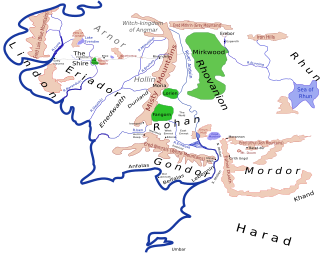

Middle-earth is the fictional setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the Miðgarðr of Norse mythology and Middangeard in Old English works, including Beowulf. Middle-earth is the human-inhabited world, that is, the central continent of the Earth, in Tolkien's imagined mythological past. Tolkien's most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, are set entirely in Middle-earth. "Middle-earth" has also become a short-hand term for Tolkien's legendarium, his large body of fantasy writings, and for the entirety of his fictional world.

The Wizards or Istari in J. R. R. Tolkien's fiction were powerful angelic beings, Maiar, who took the form of Men to intervene in the affairs of Middle-earth in the Third Age, after catastrophically violent direct interventions by the Valar, and indeed by the one god Eru Ilúvatar, in the earlier ages.

The poetry in The Lord of the Rings consists of the poems and songs written by J. R. R. Tolkien, interspersed with the prose of his high fantasy novel of Middle-earth, The Lord of the Rings. The book contains over 60 pieces of verse of many kinds; some poems related to the book were published separately. Seven of Tolkien's songs, all but one from The Lord of the Rings, were made into a song-cycle, The Road Goes Ever On, set to music by Donald Swann. All the poems in The Lord of the Rings were set to music and published on CDs by The Tolkien Ensemble.

Christianity is a central theme in J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional works about Middle-earth, but always a hidden one. This allows the book to be read at different levels, and its meaning to be applied by the reader, rather than forcing a single meaning on the reader.

England and Englishness are represented in multiple forms within J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings; it appears, more or less thinly disguised, in the form of the Shire and the lands close to it; in kindly characters such as Treebeard, Faramir, and Théoden; in its industrialised state as Isengard and Mordor; and as Anglo-Saxon England in Rohan. Lastly, and most pervasively, Englishness appears in the words and behaviour of the hobbits, both in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings.

The music of Middle-earth consists of the music mentioned by J. R. R. Tolkien in his Middle-earth books, the music written by other artists to accompany performances of his work, whether individual songs or adaptations of his books for theatre, film, radio, and games, and music more generally inspired by his books.

The prose style of J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth books, especially The Lord of the Rings, is remarkably varied. Commentators have noted that Tolkien selected linguistic registers to suit different peoples, such as simple and modern for Hobbits and more archaic for Dwarves, Elves, and Riders of Rohan. This allowed him to use the Hobbits to mediate between the modern reader and the heroic and archaic realm of fantasy. The Orcs, too, are depicted in different voices: the Orc-leader Grishnákh speaks in bullying tones, while the minor functionary Gorbag uses grumbling modern speech.

J. R. R. Tolkien, the author of the bestselling fantasy The Lord of the Rings, was largely rejected by the literary establishment during his lifetime, but has since been accepted into the literary canon, if not as a modernist then certainly as a modern writer responding to his times. He fought in the First World War, and saw the rural England that he loved built over and industrialised. His Middle-earth fantasy writings, consisting largely of a legendarium that underlies The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion that was not published until after his death, embodied his realism about the century's traumatic events, and his Christian hope.

J. R. R. Tolkien was attracted to medieval literature, especially poetry, and made use of it in his writings both in his poetry, which contained numerous pastiches of medieval verse, and in his Middle-earth writings where he embodied a wide range of medieval concepts.

Shakespeare's influence on Tolkien was substantial, despite Tolkien's professed dislike of the playwright. Tolkien disapproved in particular of Shakespeare's devaluation of elves, and was deeply disappointed by Shakespeare's prosaic explanation of how Birnam Wood came to Dunsinane Hill in Macbeth. Tolkien was influenced especially by Macbeth and A Midsummer Night's Dream, and he used King Lear for "issues of kingship, madness, and succession". He arguably drew on several other plays, including The Merchant of Venice, Henry IV, Part 1, and Love's Labour's Lost, as well as Shakespeare's poetry, for numerous effects in his Middle-earth writings. The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey suggests that Tolkien may even have felt a kind of fellow-feeling with Shakespeare, as both men were rooted in the county of Warwickshire.

In Tolkien's legendarium, ancestry provides a guide to character. The apparently genteel Hobbits of the Baggins family turn out to be worthy protagonists of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Bilbo Baggins is seen from his family tree to be both a Baggins and an adventurous Took. Similarly, Frodo Baggins has relatively outlandish Brandybuck blood. Among the Elves of Middle-earth, the highest are those whose ancestors conformed most closely to the divine will, migrating to Aman and seeing the light of the Two Trees of Valinor. Among Men, the heroic Aragorn is shown by his descent from Kings, Elves, and an immortal Maia to be of royal blood, destined to be the true King who will restore his people. Scholars have commented that in this way, Tolkien was presenting Anglo-Saxon views of kingship, though others have called his implied views racist.