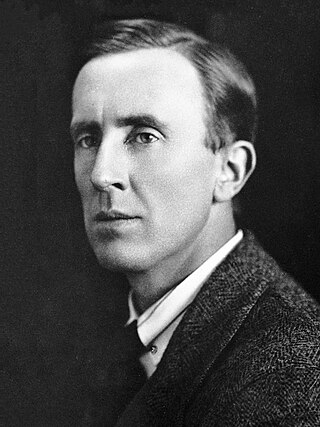

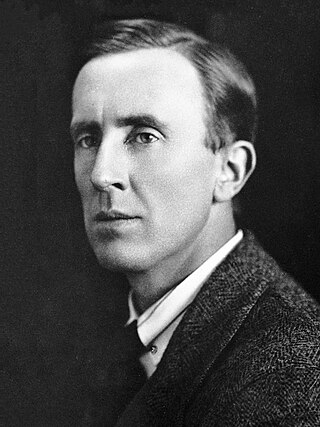

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Hobbits are a fictional race of people in the novels of J. R. R. Tolkien. About half average human height, Tolkien presented hobbits as a variety of humanity, or close relatives thereof. Occasionally known as halflings in Tolkien's writings, they live barefooted, and traditionally dwell in homely underground houses which have windows, built into the sides of hills, though others live in houses. Their feet have naturally tough leathery soles and are covered on top with curly hair.

Tuor Eladar and Idril Celebrindal are fictional characters from J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. They are the parents of Eärendil the Mariner and grandparents of Elrond Half-elven: through their progeny, they become the ancestors of the Númenóreans and of the King of the Reunited Kingdom Aragorn Elessar. Both characters play a pivotal role in The Fall of Gondolin, one of Tolkien's earliest stories; it formed the basis for a section in his later work, The Silmarillion, and was expanded as a standalone publication in 2018.

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil is a 1962 collection of poetry by J. R. R. Tolkien. The book contains 16 poems, two of which feature Tom Bombadil, a character encountered by Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings. The rest of the poems are an assortment of bestiary verse and fairy tale rhyme. Three of the poems appear in The Lord of the Rings as well. The book is part of Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the real-world history and notable fictional elements of J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy universe. It covers materials created by Tolkien; the works on his unpublished manuscripts, by his son Christopher Tolkien; and films, games and other media created by other people.

The works of J. R. R. Tolkien have generated a body of research covering many aspects of his fantasy writings. These encompass The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, along with his legendarium that remained unpublished until after his death, and his constructed languages, especially the Elvish languages Quenya and Sindarin. Scholars from different disciplines have examined the linguistic and literary origins of Middle-earth, and have explored many aspects of his writings from Christianity to feminism and race.

The word hobbit was used by J. R. R. Tolkien as the name of a race of small humanoids in his fantasy fiction, the first published being The Hobbit in 1937. The Oxford English Dictionary, which added an entry for the word in the 1970s, credits Tolkien with coining it. Since then, however, it has been noted that there is prior evidence of the word, in a 19th-century list of legendary creatures. In 1971, Tolkien stated that he remembered making up the word himself, admitting that there was nothing but his "nude parole" to support the claim that he was uninfluenced by such similar words as hobgoblin. His choice may have been affected on his own admission by the title of Sinclair Lewis's 1922 novel Babbitt. The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey has pointed out several parallels, including comparisons in The Hobbit, with the word "rabbit".

Edmund S. C. Weiner is the former co-editor of the Second Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (1985–1989) and Deputy Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (1993–present). He originally joined the OED staff in 1977, becoming the dictionary's chief philologist.

The Children of Húrin is an epic fantasy novel which forms the completion of a tale by J. R. R. Tolkien. He wrote the original version of the story in the late 1910s, revising it several times later, but did not complete it before his death in 1973. His son, Christopher Tolkien, edited the manuscripts to form a consistent narrative, and published it in 2007 as an independent work. The book is illustrated by Alan Lee. The story is one of the three "Great Tales" set in the First Age of Tolkien's Middle-earth, the other two being Beren and Lúthien and The Fall of Gondolin.

Tolkien's legendarium is the body of J. R. R. Tolkien's mythopoeic writing, unpublished in his lifetime, that forms the background to his The Lord of the Rings, and which his son Christopher summarized in his compilation of The Silmarillion and documented in his 12-volume series The History of Middle-earth. The legendarium's origins reach back to 1914, when Tolkien began writing poems and story sketches, drawing maps, and inventing languages and names as a private project to create a mythology for England. The earliest story, "The Voyage of Earendel, the Evening Star", is from 1914; he revised and rewrote the legendarium stories for most of his adult life.

J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy books on Middle-earth, especially The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, drew on a wide array of influences including language, Christianity, mythology, archaeology, ancient and modern literature, and personal experience. He was inspired primarily by his profession, philology; his work centred on the study of Old English literature, especially Beowulf, and he acknowledged its importance to his writings.

Peter Gilliver is a lexicographer and associate editor of the Oxford English Dictionary.

The Marvellous Land of Snergs is a children's fantasy, written by Edward Wyke-Smith and illustrated by the Punch cartoonist George Morrow. It was originally published in Britain by Ernest Benn in September 1927, and later published in the U.S. in 1928 by Harper & Brothers. It is notable as an inspiration source for J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit.

Middle-earth is the setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the Miðgarðr of Norse mythology and Middangeard in Old English works, including Beowulf. Middle-earth is the oecumene in Tolkien's imagined mythological past. Tolkien's most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, are set entirely in Middle-earth. "Middle-earth" has also become a short-hand term for Tolkien's legendarium, his large body of fantasy writings, and for the entirety of his fictional world.

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien is a selection of the philologist and fantasy author J. R. R. Tolkien's letters. It was published in 1981, edited by Tolkien's biographer Humphrey Carpenter, who was assisted by Christopher Tolkien. The selection, from a large mass of materials, contains 354 letters. These were written between October 1914, when Tolkien was an undergraduate at Oxford, and 29 August 1973, four days before his death. The letters are of interest both for what they show of Tolkien's life and for his interpretations of his Middle-earth writings.

The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology is a scholarly study of the Middle-earth works of J. R. R. Tolkien written by Tom Shippey and first published in 1982. The book discusses Tolkien's philology, and then examines in turn the origins of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion, and his minor works. An appendix discusses Tolkien's many sources. Two further editions extended and updated the work, including a discussion of Peter Jackson's film version of The Lord of the Rings.

England and Englishness are represented in multiple forms within J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings; it appears, more or less thinly disguised, in the form of the Shire and the lands close to it; in kindly characters such as Treebeard, Faramir, and Théoden; in its industrialised state as Isengard and Mordor; and as Anglo-Saxon England in Rohan. Lastly, and most pervasively, Englishness appears in the words and behaviour of the hobbits, both in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien's monsters are the evil beings, such as Orcs, Trolls, and giant spiders, who oppose and sometimes fight the protagonists in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. Tolkien was an expert on Old English, especially Beowulf, and several of his monsters share aspects of the Beowulf monsters; his Trolls have been likened to Grendel, the Orcs' name harks back to the poem's orcneas, and the dragon Smaug has multiple attributes of the Beowulf dragon. The European medieval tradition of monsters makes them either humanoid but distorted, or like wild beasts, but very large and malevolent; Tolkien follows both traditions, with monsters like Orcs of the first kind and Wargs of the second. Some scholars add Tolkien's immensely powerful Dark Lords Morgoth and Sauron to the list, as monstrous enemies in spirit as well as in body. Scholars have noted that the monsters' evil nature reflects Tolkien's Roman Catholicism, a religion which has a clear conception of good and evil.

J. R. R. Tolkien took part in the First World War, known then as the Great War, and began his fantasy Middle-earth writings at that time. The Fall of Gondolin was the first prose work that he created after returning from the front, and it contains detailed descriptions of battle and streetfighting. He continued the dark tone in much of his legendarium, as seen in The Silmarillion. The Lord of the Rings, too, has been described as a war book.

J. R. R. Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, created what he came to feel was a moral dilemma for himself with his supposedly evil Middle-earth peoples like Orcs, when he made them able to speak. This identified them as sentient and sapient; indeed, he portrayed them talking about right and wrong. This meant, he believed, that they were open to morality, like Men. In Tolkien's Christian framework, that in turn meant they must have souls, so killing them would be wrong without very good reason. Orcs serve as the principal forces of the enemy in The Lord of the Rings, where they are slaughtered in large numbers in the battles of Helm's Deep and the Pelennor Fields in particular.