Marie de France was a poet, likely born in France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court of King Henry II of England. Virtually nothing is known of her life; both her given name and its geographical specification come from manuscripts containing her works. However, one written description of her work and popularity from her own era still exists. She is considered by scholars to be the first woman known to write francophone verse.

According to the medieval poet Jean Bodel, the Matter of Rome is the literary cycle of Greek and Roman mythology, together with episodes from the history of classical antiquity, focusing on military heroes like Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. Bodel's division of literary cycles also included the Matter of France and the Matter of Britain. The Matter of Rome includes the Matter of Troy, consisting of romances and other texts based on the Trojan War and its legacy, including the adventures of Aeneas.

A Breton lai, also known as a narrative lay or simply a lay, is a form of medieval French and English romance literature. Lais are short, rhymed tales of love and chivalry, often involving supernatural and fairy-world Celtic motifs. The word "lay" or "lai" is thought to be derived from the Old High German and/or Old Middle German leich, which means play, melody, or song, or as suggested by Jack Zipes in The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales, the Irish word laid (song).

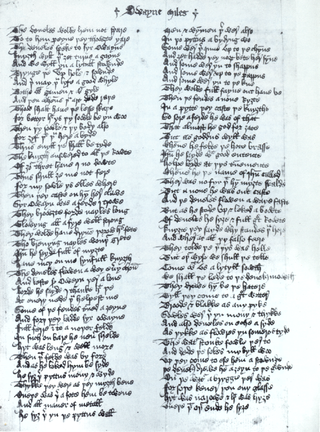

Bevis of Hampton (Old French: Beuve(s) or Bueve or Beavisde Hanton(n)e; Anglo-Norman: Boeve de Haumtone; Italian: Buovo d'Antona) or Sir Bevois was a legendary English hero and the subject of Anglo-Norman, Dutch, French, English, Venetian, and other medieval metrical chivalric romances that bear his name. The tale also exists in medieval prose, with translations to Romanian, Russian, Dutch, Irish, Welsh, Old Norse and Yiddish.

Thomas Chestre was the author of a 14th-century Middle English romance Sir Launfal, a verse romance of 1045 lines based ultimately on Marie de France's Breton lay Lanval. He was possibly also the author of the 2200-line Libeaus Desconus, a story of Sir Gawain's son Gingalain based upon similar traditions to those that inspired Renaut de Beaujeu's late-12th-century or early-13th-century Old French romance Le Bel Inconnu, and also possibly of a Middle English retelling of the mid-13th-century Old French romance Octavian. Geoffrey Chaucer parodied Libeaus Desconus, among other Middle English romances, in his Canterbury Tale of Sir Thopas.

Sir Launfal is a 1045-line Middle English romance or Breton lay written by Thomas Chestre dating from the late 14th century. It is based primarily on the 538-line Middle English poem Sir Landevale, which in turn was based on Marie de France's lai Lanval, written in a form of French understood in the courts of both England and France in the 12th century. Sir Launfal retains the basic story told by Marie and retold in Sir Landevale, augmented with material from an Old French lai Graelent and a lost romance that possibly featured a giant named Sir Valentyne. This is in line with Thomas Chestre's eclectic way of creating his poetry.

In Greek mythology, the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice concerns the fateful love of Orpheus of Thrace for the beautiful Eurydice. Orpheus was the son of Oeagrus and the muse Calliope. It may be a late addition to the Orpheus myths, as the latter cult-title suggests those attached to Persephone. The subject is among the most frequently retold of all Greek myths, being featured in numerous works of literature, operas, ballets, paintings, plays, musicals, and more recently, films and video games.

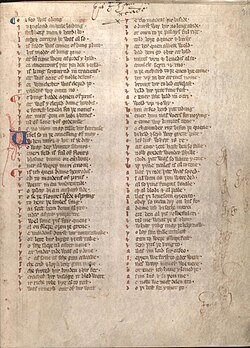

Emaré is a Middle English Breton lai, a form of mediaeval romance poem, told in 1035 lines. The author of Emaré is unknown and it exists in only one manuscript, Cotton Caligula A. ii, which contains ten metrical narratives. Emaré seems to date from the late fourteenth century, possibly written in the North East Midlands. The iambic pattern is rather rough.

In Greek mythology, Orpheus was a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with Jason and the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece, and even descended into the underworld of Hades, to recover his lost wife Eurydice.

Eurydice was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, whom Orpheus tried to bring back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Octavian is a 14th-century Middle English verse translation and abridgement of a mid-13th century Old French romance of the same name. This Middle English version exists in three manuscript copies and in two separate compositions, one of which may have been written by the 14th-century poet Thomas Chestre who also composed Libeaus Desconus and Sir Launfal. The other two copies are not by Chestre and preserve a version of the poem in regular twelve-line tail rhyme stanzas, a verse structure that was popular in the 14th century in England. Both poetic compositions condense the Old French romance to about 1800 lines, a third of its original length, and relate “incidents and motifs common in legend, romance and chanson de geste.” The story describes a trauma that unfolds in the household of Octavian, later the Roman Emperor Augustus, whose own mother deceives him into sending his wife and his two newborn sons into exile and likely death. After many adventures, the family are at last reunited and the guilty mother is appropriately punished.

Sir Gowther is a relatively short Middle English tail-rhyme romance in twelve-line stanzas, found in two manuscripts, each dating to the mid- or late-fifteenth century. The poem tells a story that has been variously defined as a secular hagiography, a Breton lai and a romance, and perhaps "complies to a variety of possibilities". An adaptation of the story of Robert the Devil, the story follows the fortunes of Sir Gowther from birth to death, from his childhood as the son of a fiend, his wicked early life, through contrition and a penance imposed by the Pope involving him in a lowly and humiliating position in society, and to his eventual rise, via divine miracles, as a martial hero and ultimately to virtual canonization. But despite this saintly end, "like many other lays and romances, Sir Gowther derives much of its inspiration from a rich and vastly underappreciated folk tradition."

Sir Eglamour of Artois is a Middle English verse romance that was written sometime around 1350. It is a narrative poem of about 1300 lines, a tail-rhyme romance that was quite popular in its day, judging from the number of copies that have survived – four manuscripts from the 15th century or earlier and a manuscript and five printed editions from the 16th century. The poem tells a story that is constructed from a large number of elements found in other medieval romances. Modern scholarly opinion has been critical of it because of this, describing it as unimaginative and of poor quality. Medieval romance as a genre, however, concerns the reworking of "the archetypal images of romance" and if this poem is viewed from a 15th-century perspective as well as from a modern standpoint – and it was obviously once very popular, even being adapted into a play in 1444 – one might find a "romance [that] is carefully structured, the action highly unified, the narration lively."

Sir Perceval of Galles is a Middle English Arthurian verse romance whose protagonist, Sir Perceval (Percival), first appeared in medieval literature in Chrétien de Troyes' final poem, the 12th-century Old French Conte del Graal, well over one hundred years before the composition of this work. Sir Perceval of Galles was probably written in the northeast Midlands of England in the early 14th century, and tells a markedly different story to either Chretien's tale or to Robert de Boron's early 13th-century Perceval. Found in only a single manuscript, and told with a comic liveliness, it omits any mention of a graal or a Grail.

Sir Tryamour is a Middle English romance dated to the late fourteenth century. The source is unknown and, like almost all of the Middle English romances to have survived, its author is anonymous. The 1,719-line poem is written in irregular tail rhyme stanzas composed in the Northeast Midlands dialect. There are textual ambiguities and obscurities that suggest corruption or "loose transmission." Consequently, interpretations, glosses and notes vary between editions, sometimes substantially.

The Erl of Toulouse is a Middle English chivalric romance centered on an innocent persecuted wife. It claims to be a translation of a French lai, but the original lai is lost. It is thought to date from the late 14th century, and survives in four manuscripts of the 15th and 16th centuries. The Erl of Toulouse is written in a north-east Midlands dialect of Middle English.

Sir Cleges is a medieval English verse chivalric romance written in tail-rhyme stanzas in the late 14th or early 15th century. It is clearly a minstrel tale, praising giving gifts to minstrels, and punishing the servants who might make it impossible for a minstrel in a noble household. Corrupt officials are central to it.

Beves of Hamtoun, also known as Beves of Hampton, Bevis of Hampton or Sir Beues of Hamtoun, is an anonymous Middle English romance of 4620 lines, dating from around the year 1300, which relates the adventures of the English hero Beves in his own country and in the Near East. It is often classified as a Matter of England romance. It is a paraphrase or loose translation of the Anglo-Norman romance Boeuve de Haumton, and belongs to a large family of romances in many languages, including Welsh, Russian and even Yiddish versions, all dealing with the same hero.

Sir Degaré is a Middle English romance of around 1,100 verse lines, probably composed early in the fourteenth century. The poem is often categorised as a Breton lai because it is partly set in Brittany, involves an imagined Breton royal family, and contains supernatural elements similar to those found in some other examples, such as Sir Orfeo. Sir Degaré itself does not explicitly claim to be a Breton lai. The poem is anonymous, and no extant source has ever firmly been identified.

Guiomar is the best known name of a character appearing in many medieval texts relating to the Arthurian legend, often in relationship with Morgan le Fay or a similar fairy queen type character.