Context

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973) was a scholar of English literature, a philologist and medievalist interested in language and poetry from the Middle Ages, especially that of Anglo-Saxon England and Northern Europe. His professional knowledge of Beowulf , telling of a pagan world but with a Christian narrator, helped to shape his fictional world of Middle-earth. His intention to create what has been called "a mythology for England" [4] led him to construct not only stories but a fully-formed world, Middle-earth, with invented languages, peoples, cultures, and history. Among his many influences were his own Roman Catholic faith, and medieval languages and literature. He is best known as the author of the high fantasy works The Hobbit (1937), The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955), and The Silmarillion (1977), all set in Middle-earth. [5]

The early literary reception of The Lord of the Rings was divided between enthusiastic support by figures such as W. H. Auden and C. S. Lewis, and outright rejection by critics such as Edmund Wilson. [6]

Paul H. Kocher was a scholar of English literature. [7] The book was published before The Silmarillion appeared to confirm several of Kocher's inferences about the mythical history of Middle-earth. [8]

Book

Publication history

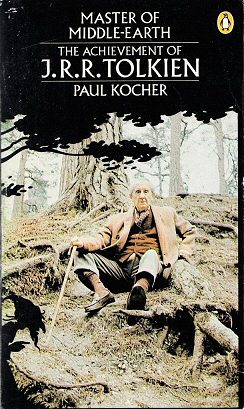

The book was first published in hardback by Houghton Mifflin in the United States in October 1972. The first British edition was brought out by Thames & Hudson in hardback in 1973, with the title Master of Middle-earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Paperback editions followed: by Penguin Books in 1974, Ballantine Books in 1977, Pimlico in 2002, and Del Rey in 2003. [9] The book has been translated into Dutch, French, German, Italian, Polish, and Swedish. [10] The book was reprinted several times, such as in New York: Ballantine Books, 1977; [11] New York: Del Rey, 1982; [12] and London: Pimlico, 2002. [13]

Translations include:

- into French by Jean Markale as Le royaume de la terre du milieu: Les clés de l'oeuvre de J.R.R. Tolkien. Paris: Retz, 1981.

- into Italian, Il maestro della Terra di Mezzo, Rome: Bompiani, 2011.

- into Swedish by Åke Ohlmarks, Tolkiens sagovärld: En vägledning. Stockholm: AWE/Geber, 1989; and Stockholm: Geber, 1973.

- into Dutch by Max Schuchart, Tolkien: Meester van midden-aarde: Zijn romans en verhalen. The Hague: Bert Bakker, 1973.

- into Polish by Radosław Kot as Mistrz Śródziemia. Warsaw: Amber, 1998.

Synopsis

The book has seven chapters, a "Bibliographical Note" on Tolkien's publications, academic notes, and a full index. The chapters cover:

- "Middle-earth: An Imaginary World" – how Tolkien blends fantasy and reality to create his world. Kocher quotes Tolkien's statement about creating secondary worlds, that they have to command a kind of belief, and while they may contain dwarfs, trolls, and dragons, these have to be set in a world with realistic features of sea and sky and earth. He notes that Middle-earth is "our earth as it was long ago".

- " The Hobbit " – on the quality of Tolkien's children's book. Kocher suggests that the key is to think of Tolkien sitting by the fireside telling the story to a group of children: in the text, he addresses the reader directly. "Jocular interjections" help to maintain "a playful intimacy", while the text "is full of sound effects". All the same, the intended readership is vague, as some passages, like Bard's claim to Smaug's treasure, are more for adults. He notes, too, the change in the "true story" of how Bilbo got the One Ring in the 1966 prologue to The Lord of the Rings, helping to smooth the transition between the two novels.

- "Cosmic Order" – on the cosmology of Middle-earth, from the role of Wizards to the godlike Valar. Kocher discerns a "moral dynamism in the universe to which each [protagonist] freely contributes, without exactly knowing how"; in his view the thoughtful characters say enough to imply clearly "the order in which they believe" and the unseen "planner operating through it". He considers, too, the nature of death and immortality for elves and men.

- "Sauron and the Nature of Evil" – on the questions of evil and the addictive nature of the temptation of the Ring, including other evil figures like Saruman and Shelob. Kocher discusses how Tolkien deals with the different theories of evil in Christianity, including the Manichean view (evil is as powerful as good), and the question of how Orcs were made evil if "the Shadow that bred them can only mock, it cannot make".

- "The Free Peoples" – on how Tolkien portrays different peoples, cultures, and languages by varying his prose. Kocher argues that far from using stereotyped characters or merely telling an adventure story, Tolkien explores both the individuals and the nature of their races, including Elves, Hobbits, Dwarves, Men, and Ents. In his view, "Tolkien's real mastery ... consists in his power to establish for each individual race a personality that is unmistakably its own."

- "Aragorn" – arguing that the ranger who becomes King is the real hero of The Lord of the Rings. Kocher writes that Aragorn is a "complex man", the most difficult to "know truly" of any of the major characters in The Lord of the Rings: not least because the reader does not "see him whole" with the details of his life and love until Appendix A's "The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen", which Kocher calls "beautiful". He examines how Aragorn wins his way into the Hobbits' childish expedition, keeping "powerful feelings under rein". He analyses, too, the rivalry of Aragorn and Boromir, and how "a combination of tact and boldness" wins Aragorn the recognition he wants from his rival; followed by his success with Éomer, and how he deals with Éowyn's love for him. Then "he grows in strength and sureness of touch with each passing test" until he regains the throne of Gondor.

- "Seven Leaves" – on seven of Tolkien's minor works: "Leaf by Niggle", The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun , Farmer Giles of Ham , The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son , Smith of Wootton Major , Imram , and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil . Kocher examines the varying techniques Tolkien uses in these diverse stories and poems, down to the "series of puns and comic touches" which keep "The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon" from seeming tragic. All the same, the tone of the poems in the collection grows "increasingly sombre" until "The Sea-Bell's" longing for another world becomes unmistakable. Kocher notes, too, the irony in the poem and play The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son, when Tolkien "lauds the dead [Anglo-Saxon] leader for that very quality that destroyed the people he was supposed to guard and guide".

Impact

Reception

Perceptions of Kocher's work have changed with the publication of The Silmarillion and of The History of Middle-earth, which appeared after the contemporary reviews were written. [14]

Contemporary

The scholar of English literature, Glenn Edward Sadler, reviewing the book in Christianity Today in 1973, wrote that Kocher had provided a "survey narrative", both scholarly and readable, of Tolkien's blend of reality and fantasy. The book ably described Tolkien's "theory of artistic creation (secondary world building), major philosophical and religious ideas, and moral imperatives", and evaluated his construction of myth. [15]

Veronica Kennedy, in her 1973 review for Extrapolation , praised Kocher's boldness in attempting to cover the whole of Tolkien's Middle-earth oeuvre, but thought that the origins of The Lord of the Rings in medieval "epics and romances" like The Faerie Queene and Sir Gawain should have been explored in more depth, as well as the influence of Tolkien's contemporaries like C. S. Lewis. [16]

Nicholas Tucker, writing in New Society in 1973, criticised the book, calling it "yet another undistinguished addition" to the body of literature on Tolkien. Tucker further wrote that "Nor is Master of Middle-Earth the type of book one could recommend 'for enthusiasts only'. I can't imagine many readers of Tolkien's mysterious, numinous story would want this sort of chattering commentary, ever-eager to analyse character, hand out good conduct marks for heroism, and really dig, say, the difference between a dwarf and an elf." [17]

Nancy-Lou Patterson, in Mythlore in 1975, welcomed the book, stating that "Kocher's Master of Middle-earth is just the sort of study of Tolkien's ability as a master 'sub-creator' which his admirers have often felt ought to be written and which many of them will probably wish they had had the good sense to write themselves. ... The result is a thorough, brilliant, and warmly sympathetic exploration of the several 'other worlds' of which Tolkien has become the master." [18]

Later

Charles W. Nelson, in Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts , noting that the book was one of the first scholarly studies of Tolkien, wrote in 1994 that it contained "one of the most complete discussions of love and emotional attachments in the trilogy, including a fascinating treatment of self-love and its injurious affects on the evil characters". [19] The science fiction author Karen Haber called the book the "highest point" of academic criticism of Tolkien during his lifetime. [20]

The scholar of religion Paul Nolan Hyde wrote in Religious Educator that Kocher was one of the early scholars who took Tolkien seriously, praising rather than decrying his prose style and his "real mastery as a writer" which (he quotes Kocher) "consists in his power to establish for each individual race a personality that is unmistakably its own... Further, each race has not only its gifts but also its private tragedy, which it must try to overcome as best it can." [21]

The Tolkien scholar Richard C. West wrote in The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia that Kocher had written "the finest book from this [early] period ... [it] looks closely and deeply at the whole body of Tolkien's work to that time. Its insights have held up well for decades." [6]

The evolutionary psychiatrist and Tolkien critic Bruce Charlton wrote that the book was the "first really good piece of book length critical work" on Tolkien, noting that it came out just before Tolkien's death. It thus embodied "a lost perspective", absent all Tolkien's posthumously-published writings, including the 12-volume The History of Middle-earth which appeared in the following decades. In Charlton's view, the book therefore has permanent value. He notes that Kocher flags up or discusses in detail nearly all the key points about Tolkien, making educated inferences that were later confirmed by Christopher Tolkien's lengthy research among his father's papers. [14]

Carol Leibiger, writing in Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts , commented that "Kocher ... was unable to include The Silmarillion ... in his study, and he never revised this work to include it, which diminishes its usefulness for any audience seeking to understand Tolkien's Middle-Earth works." [22]

Analysis

The Jesuit priest John L. Treloar wrote in Mythlore that Kocher notices Tolkien's tendency to move away from personifying evil towards making it an abstract entity, but ascribes this to Tolkien's familiarity as a Roman Catholic with the writings of Thomas Aquinas. Treloar argues that Aquinas derived his concepts from Saint Augustine. He explains that Augustine had argued that God is entirely good, making it awkward to explain how evil could exist; Augustine wrestled with this, concluding that everything that God had created was good in the beginning. Treloar writes that the artist in Tolkien would have been attracted by Augustine's struggle. He notes that if Kocher had had the help of The Silmarillion, he might have seen that Tolkien's Augustinian view of evil as the absence of good was "even more pervasive [in Middle-earth] than Kocher realizes". [23]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.