Adûnaic is one of the fictional languages devised by J. R. R. Tolkien for his fantasy works.

Elendil is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. He is mentioned in The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales. He was the father of Isildur and Anárion, last lord of Andúnië on the island of Númenor, and having escaped its downfall by sailing to Middle-earth, became the first High King of Arnor and Gondor. In the Last Alliance of Men and Elves, Elendil and Gil-galad laid siege to the Dark Lord Sauron's fortress of Barad-dûr, and fought him hand-to-hand for the One Ring. Both Elendil and Gil-galad were killed, and Elendil's son Isildur took the Ring for himself.

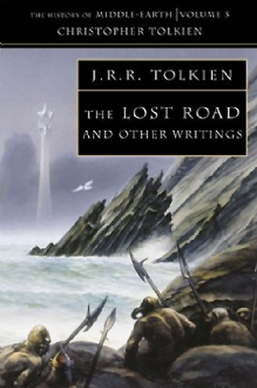

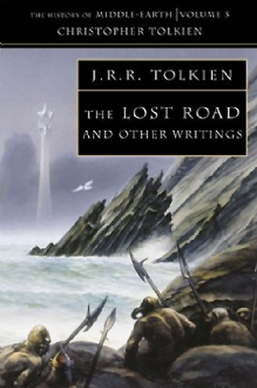

The Lost Road and Other Writings – Language and Legend before 'The Lord of the Rings' is the fifth volume, published in 1987, of The History of Middle-earth, a series of compilations of drafts and essays written by J. R. R. Tolkien in around 1936–1937. It was edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher.

Ælfwine the mariner is a fictional character found in various early versions of J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium. Tolkien envisaged Ælfwine as an Anglo-Saxon who visited and befriended the Elves and acted as the source of later mythology. Thus, in the frame story, Ælfwine is the stated author of the various translations in Old English that appear in the twelve-volume The History of Middle-earth edited by Christopher Tolkien.

The Round World Version is an alternative creation myth to the version of J.R.R. Tolkien's legendarium as it appears in The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings. In that version, the Earth was created flat and was changed to round as a cataclysmic event during the Second Age in order to prevent direct access by Men to Valinor, home of the immortals. In the Round World Version, the Earth is created spherical from the beginning.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the real-world history and notable fictional elements of J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy universe. It covers materials created by Tolkien; the works on his unpublished manuscripts, by his son Christopher Tolkien; and films, games and other media created by other people.

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the history of Arda, also called the history of Middle-earth, began when the Ainur entered Arda, following the creation events in the Ainulindalë and long ages of labour throughout Eä, the fictional universe. Time from that point was measured using Valian Years, though the subsequent history of Arda was divided into three time periods using different years, known as the Years of the Lamps, the Years of the Trees, and the Years of the Sun. A separate, overlapping chronology divides the history into 'Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar'. The first such Age began with the Awakening of the Elves during the Years of the Trees and continued for the first six centuries of the Years of the Sun. All the subsequent Ages took place during the Years of the Sun. Most Middle-earth stories take place in the first three Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar.

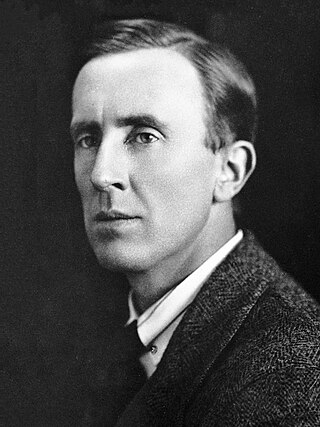

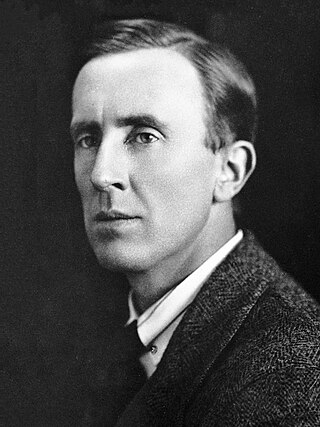

Tolkien's legendarium is the body of J. R. R. Tolkien's mythopoeic writing, unpublished in his lifetime, that forms the background to his The Lord of the Rings, and which his son Christopher summarized in his compilation of The Silmarillion and documented in his 12-volume series The History of Middle-earth. The legendarium's origins reach back to 1914, when Tolkien began writing poems and story sketches, drawing maps, and inventing languages and names as a private project to create a mythology for England. The earliest story, "The Voyage of Earendel, the Evening Star", is from 1914; he revised and rewrote the legendarium stories for most of his adult life.

Tolkien's Legendarium: Essays on The History of Middle-earth is a collection of scholarly essays edited by Verlyn Flieger and Carl F. Hostetter on the 12 volumes of The History of Middle-earth, relating to J. R. R. Tolkien's fiction and compiled and edited by his son, Christopher. It was published by Greenwood Press in 2000. That series comprises a substantial part of "Tolkien's legendarium", the body of Tolkien's mythopoeic writing that forms the background to his The Lord of the Rings and which Christopher Tolkien summarized in his construction of The Silmarillion.

Númenor, also called Elenna-nórë or Westernesse, is a fictional place in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings. It was the kingdom occupying a large island to the west of Middle-earth, the main setting of Tolkien's writings, and was the greatest civilization of Men. However, after centuries of prosperity many of the inhabitants ceased to worship the One God, Eru Ilúvatar, and rebelled against the Valar, resulting in the destruction of the island and the death of most of its people. Tolkien intended Númenor to allude to the legendary Atlantis.

Isildur is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth, the elder son of Elendil, descended from Elros, the founder of the island Kingdom of Númenor. He fled with his father when the island was drowned, becoming in his turn King of Arnor and Gondor. He cut the Ring from Sauron's hand, but instead of destroying it, was corrupted by its power and claimed it for his own. He was killed by orcs, and the Ring was lost in the River Anduin. This set the stage for the Ring to pass to Gollum and then to Bilbo, as told in The Hobbit; that in turn provided the central theme, the quest to destroy the Ring, for The Lord of the Rings.

The Silmarillion is a book consisting of a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited, partly written, and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by Guy Gavriel Kay, who became a fantasy author. It tells of Eä, a fictional universe that includes the Blessed Realm of Valinor, the ill-fated region of Beleriand, the island of Númenor, and the continent of Middle-earth, where Tolkien's most popular works—The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—are set. After the success of The Hobbit, Tolkien's publisher, Stanley Unwin, requested a sequel, and Tolkien offered a draft of the writings that would later become The Silmarillion. Unwin rejected this proposal, calling the draft obscure and "too Celtic", so Tolkien began working on a new story that eventually became The Lord of the Rings.

J. R. R. Tolkien built a process of decline and fall in Middle-earth into both The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings.

The philologist and author J. R. R. Tolkien set out to explore time travel and distortions in the passage of time in his fiction in a variety of ways. The passage of time in The Lord of the Rings is uneven, seeming to run at differing speeds in the realms of Men and of Elves. In this, Tolkien was following medieval tradition in which time proceeds differently in Elfland. The whole work, too, following the theory he spelt out in his essay "On Fairy-Stories", is meant to transport the reader into another time. He built a process of decline and fall in Middle-earth into the story, echoing the sense of impending destruction of Norse mythology. The Elves attempt to delay this decline as far as possible in their realms of Rivendell and Lothlórien, using their Rings of Power to slow the passage of time. Elvish time, in The Lord of the Rings as in the medieval Thomas the Rhymer and the Danish Elvehøj, presents apparent contradictions. Both the story itself and scholarly interpretations offer varying attempts to resolve these; time may be flowing faster or more slowly, or perceptions may differ.

J. R. R. Tolkien used frame stories throughout his Middle-earth writings, especially his legendarium, to make the works resemble a genuine mythology written and edited by many hands over a long period of time. He described in detail how his fictional characters wrote their books and transmitted them to others, and showed how later in-universe editors annotated the material.

Tolkien's Art: 'A Mythology for England' is a 1979 book of Tolkien scholarship by Jane Chance, writing then as Jane Chance Nitzsche. The book looks in turn at Tolkien's essays "On Fairy-Stories" and "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics"; The Hobbit; the fairy-stories "Leaf by Niggle" and "Smith of Wootton Major"; the minor works "Lay of Autrou and Itroun", "The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth", "Imram", and Farmer Giles of Ham; The Lord of the Rings; and very briefly in the concluding section, The Silmarillion. In 2001, a second edition extended all the chapters but still treated The Silmarillion, that Tolkien worked on throughout his life, as a sort of coda.

J. R. R. Tolkien decided to increase the reader's feeling that the story in his 1954–55 book The Lord of the Rings was real, by framing the main text with an elaborate editorial apparatus that extends and comments upon it. This material, mainly in the book's appendices, effectively includes a fictional editorial figure much like himself who is interested in philology, and who says he is translating a manuscript which has somehow come into his hands, having somehow survived the thousands of years since the Third Age. He called the book a heroic romance, giving it a medieval feeling, and describing its time-frame as the remote past. Among the steps he took to make its setting, Middle-earth, believable were to develop its geography, history, peoples, genealogies, and unseen background in great detail, complete with editorial commentary in each case.

Tolkien has often been supposed to have spoken of wishing to create "a mythology for England". It seems he never used the actual phrase, but various commentators have found his biographer Humphrey Carpenter's phrase appropriate as a description of much of his approach in creating Middle-earth, and the legendarium that lies behind The Silmarillion.

The Old Straight Road, the Straight Road, the Lost Road, or the Lost Straight Road, is J. R. R. Tolkien's conception, in his fantasy world of Arda, of the route that his Elves are able to follow to reach the earthly paradise of Valinor, realm of the godlike Valar. The tale is mentioned in The Silmarillion and in The Lord of the Rings, and documented in The Lost Road and Other Writings. The Elves are immortal, but may grow weary of the world, and then sail across the Great Sea to reach Valinor. The men of Númenor are persuaded by Sauron, servant of the first Dark Lord Melkor, to attack Valinor to get the immortality they feel should be theirs. The Valar ask for help from the creator, Eru Ilúvatar. He destroys Númenor and its army, in the process reshaping Arda into a sphere, and separating it and its continent of Middle-earth from Valinor so that men can no longer reach it. But the Elves can still set sail from the shores of Middle-earth in ships, bound for Valinor: they sail into the Uttermost West, following the Old Straight Road.

A Question of Time: J.R.R. Tolkien's Road to Faërie is a 1997 book of literary analysis by Verlyn Flieger of J. R. R. Tolkien's explorations of the nature of time in his Middle-earth writings, interpreted in the light of J. W. Dunne's 1927 theory of time, and Dunne's view that dreams gave access to all dimensions of time. Tolkien read Dunne's book carefully and annotated his copy with his views of the theory. A Question of Time examines in particular Tolkien's two unfinished time-travel novels, The Lost Road and The Notion Club Papers, and the time-travel aspects of The Lord of the Rings. These encompass Frodo's dreams and the land of the Elves, Lothlórien.