The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Participants were representatives of all European powers and other stakeholders. The Congress was chaired by Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich, and was held in Vienna from September 1814 to June 1815.

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, 1st Prince of Benevento, then Prince of Talleyrand, was a French secularized clergyman, statesman, and leading diplomat. After studying theology, he became Agent-General of the Clergy in 1780. In 1789, just before the French Revolution, he became Bishop of Autun. He worked at the highest levels of successive French governments, most commonly as foreign minister or in some other diplomatic capacity. His career spanned the regimes of Louis XVI, the years of the French Revolution, Napoleon, Louis XVIII, Charles X, and Louis Philippe I. Those Talleyrand served often distrusted him but, like Napoleon, found him extremely useful. The name "Talleyrand" has become a byword for crafty and cynical diplomacy.

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein, known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternich, was a German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian Empire. A conservative, Metternich was at the center of the European balance of power known as the Concert of Europe for three decades as Austrian foreign minister from 1809 and chancellor from 1821 until the liberal Revolutions of 1848 forced his resignation.

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the status quo ante—the previous political state of society—which the person believes possessed positive characteristics that are absent from contemporary society. As a descriptor term, reactionary derives from the ideological context of the left–right political spectrum. As an adjective, the word reactionary describes points of view and policies meant to restore a status quo ante.

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a multinational European great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, it was the third most populous monarchy in Europe after the Russian Empire and the United Kingdom, while geographically, it was the third-largest empire in Europe after the Russian Empire and the First French Empire.

The Conservative Order was the period in political history of Europe after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. From 1815 to 1830, a conscious program by conservative statesmen, including Metternich and Castlereagh, was put into place to contain revolution and revolutionary forces by restoring the old orders, particularly the previously-ruling aristocracies. On the other hand, in South America, in light of the Monroe Doctrine, the Spanish and the Portuguese colonies gained independence.

The Ultra-royalists were a French political faction from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration. An Ultra was usually a member of the nobility of high society who strongly supported Roman Catholicism as the state and only legal religion of France, the Bourbon monarchy, traditional hierarchy between classes and census suffrage, while rejecting the political philosophy of popular will and the interests of the bourgeoisie along with their liberal and democratic tendencies.

The unification of Germany was a process of building the first nation-state for Germans with federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany. It commenced on 18 August 1866 with adoption of the North German Confederation Treaty establishing the North German Confederation, initially a military alliance de facto dominated by Prussia which was subsequently deepened through adoption of the North German Constitution.

The October Diploma was a constitution of the Austrian Empire adopted by Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph on 20 October 1860. The Diploma was written by the Minister of Interior, Agenor Gołuchowski. It attempted to increase the power of the conservative nobles by giving them more power over their own lands through a program of aristocratic federalism. This policy was a failure almost from the start, and Franz Joseph was forced to make further concessions in the February Patent of 1861. Even so, historians have argued that the October Diploma began the "constitutional" period of the empire.

Friedrich von Gentz was a Prussian-Austrian diplomat and a writer. With Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich he was one of the main forces behind the organisation, management and protocol of the Congress of Vienna.

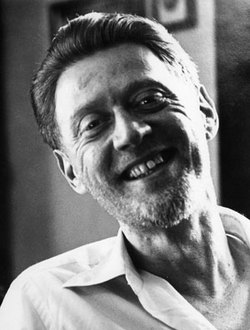

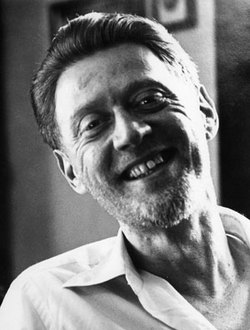

Peter Robert Edwin Viereck was an American writer, poet and professor of history at Mount Holyoke College. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1949 for the collection Terror and Decorum. In 1955 he was a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Florence.

Felix Ludwig Johann Friedrich, Prince of Schwarzenberg was a Bohemian nobleman and an Austrian statesman who restored the Austrian Empire as a European great power following the Revolutions of 1848. He served as Minister-President of the Austrian Empire and Foreign Minister of the Austrian Empire from 1848 to 1852.

Josephinism is a name given collectively to the domestic policies of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor (1765–1790). During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy (1780–1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms to remodel Austria in the form of what liberals saw as an ideal Enlightened state. This provoked severe resistance from powerful forces within and outside his empire, but ensured that he would be remembered as an "enlightened ruler" by historians from then to the present day.

Vormärz was a period in the history of Germany preceding the 1848 March Revolution in the states of the German Confederation. The beginning of the period is less well-defined. Some place the starting point directly after the fall of Napoleon and the establishment of the German Confederation in 1815. Others, typically those who emphasise the Vormärz as a period of political uprising, place the beginning at the French July Revolution of 1830.

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history to date.

Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias, sometimes anglicized as John Capodistrias, was a Greek statesman who was one of the most distinguished politicians and diplomats of 19th-century Europe.

The term Dreissiger (Thirtiers) refers to liberal intellectuals who left Germany and came to the United States in the 1830s to escape political repression. In a broader sense, it refers to immigrants from across Germany, and including members of every social and economic class, who immigrated to the US during this period.

The Liberal Party was a loosely organised political party in Mexico from 1822 to 1911. Strongly influenced by French Revolutionary thought, and the republican institutions of the United States, it championed the principles of 19th-century liberalism, and promoted republicanism, federalism, and anti-clericalism. They were opposed by, and fought several civil wars against, the Conservative Party.

The Conservative Party was a political faction in Mexico between 1823 and 1867, which became a loosely organized political party after 1849.

Heinrich Ritter von Srbik was an Austrian historian who became involved on the fringes of politics before and during the Hitler years.