Spinning the myth

The narrative of the heroic past fell to such nationalist German historians as Heinrich von Treitschke (1834–1896), Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903), and Heinrich von Sybel (1817–1895), to name three. Treitschke in particular viewed Prussia as the logical agent of unification. [3] These historical arguments can also be called the grand, or great, narratives but they are inherently ethnocentric, at least when applied to the historical process. [4] Treitschke's History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century, published in 1879, has perhaps a misleading title: it privileges the history of Prussia over the history of other German states, and it tells the story of the German-speaking peoples through the guise of Prussia's destiny to unite all German states under its leadership. The creation of this myth established Prussia as Germany's savior; it was the destiny of all Germans to be united, this myth maintains, and it was Prussia's destiny to accomplish this. [5] According to this story, Prussia played the dominant role in bringing the German states together as a nation-state; only Prussia could protect German liberties from being crushed by French or Russian influence. This interpretation emphasizes Prussia's role in saving Germans from the resurgence of Napoleon's power in 1814, at Waterloo, creating some semblance of economic unity through the Zollverein (German customs union), and uniting Germans under one proud flag after the defeat of France in the Franco Prussian War in 1871. [6]

Deconstructing the myth

After World War II, various historians of Germany sought to re-examine the German past, in part to understand the immediate German past and the Holocaust, and in part to understand Germany's supposed democratic deficit: Theoretically, Germans were inexperienced with democracy and self-government because their experience in unification came under the leadership of the least democratic of the German states (Prussia). This inevitably led to, first, World War I, and second the failure of the Weimar Republic, third, to the rise of National Socialism, and fourth, to World War II.

The Borussian myth was linked to the Sonderweg theory of Germany's peculiar road to modernity. [7] The set of circumstances that predated the Unification, for example, the so-called failure of the 1848 German revolutions and the elimination of Austria as a possible leader in the unification process strengthen the myth's appeal. In this way, teleological arguments tend to work backward from an event, to describe and rationalize all trends leading to it; [8] they are genealogical —trace from the present to the past—rather than historical, which explores the past to the present.

In the 1970s, and later, as social and cultural historians examined nineteenth-century German history in greater depth, they realized that not only was there a vibrant and lively German culture without Prussia, but they also deconstructed significant elements of the Sonderweg theory as well. They discovered, for example, that the 1848 Revolutions in Germany actually had some significant successes. [9] Indeed, the history of 19th-century Germany was not a long process of grinding under the heel of Prussian militarism, but instead a process of economic expansion, testing of democratic institutions, the writing and testing of constitutions, and the creation of social insurance systems to maintain long term economic security. [10]

The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich, or simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic.

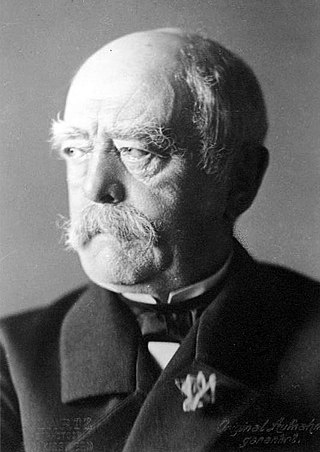

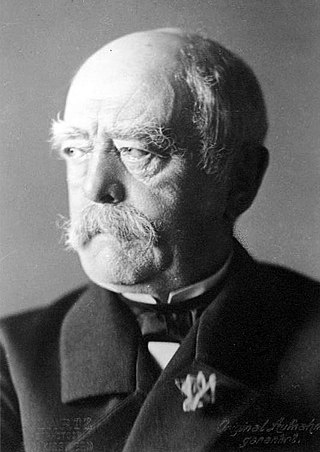

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg, born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a Prussian and later German statesman and diplomat.

The German Confederation was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved in 1806.

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as Deutscher Krieg, Deutscher Bruderkrieg and by a variety of other names, was fought in 1866 between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia, with each also being aided by various allies within the German Confederation. Prussia had also allied with the Kingdom of Italy, linking this conflict to the Third Independence War of Italian unification. The Austro-Prussian War was part of the wider rivalry between Austria and Prussia, and resulted in Prussian dominance over the German states.

Heinrich Gotthard Freiherr von Treitschke was a German historian, political writer and National Liberal member of the Reichstag during the time of the German Empire. He was an extreme nationalist, who favored German colonialism and opposed the British Empire. He also opposed Catholics, Poles, Jews and socialists inside Germany.

Whig history is an approach to historiography that presents history as a journey from an oppressive and benighted past to a "glorious present". The present described is generally one with modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy: it was originally a satirical term for the patriotic grand narratives praising Britain's adoption of constitutional monarchy and the historical development of the Westminster system. The term has also been applied widely in historical disciplines outside of British history to describe "any subjection of history to what is essentially a teleological view of the historical process". When the term is used in contexts other than British history, "whig history" (lowercase) is preferred.

The unification of Germany was a process of building the first nation-state for Germans with federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany. It commenced on 18 August 1866 with adoption of the North German Confederation Treaty establishing the North German Confederation, initially a military alliance de facto dominated by Prussia which was subsequently deepened through adoption of the North German Constitution. The process symbolically concluded when most of south German states joined the North German Confederation with the ceremonial proclamation of the German Empire i.e. the German Reich having 25 member states and led by the Kingdom of Prussia of Hohenzollerns on 18 January 1871; the event was later celebrated as the customary date of the German Empire's foundation, although the legally meaningful events relevant to the accomplishment of unification occurred on 1 January 1871 and 4 May 1871.

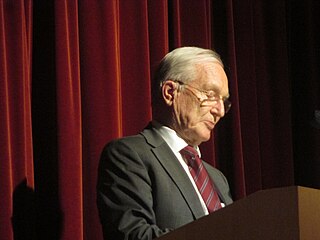

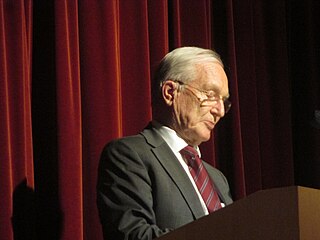

Hans-Ulrich Wehler was a German left-liberal historian known for his role in promoting social history through the "Bielefeld School", and for his critical studies of 19th-century Germany.

Klaus Hildebrand is a German liberal-conservative historian whose area of expertise is 19th–20th-century German political and military history.

The Erfurt Union was a short-lived union of German states under a federation, proposed by the Kingdom of Prussia at Erfurt, for which the Erfurt Union Parliament, officially lasting from March 20 to April 29, 1850, was opened at the former Augustinian monastery in Erfurt. The union never came into effect, and was seriously undermined in the Punctation of Olmütz under immense pressure from the Austrian Empire.

Sonderweg refers to the theory in German historiography that considers the German-speaking lands or the country of Germany itself to have followed a course from aristocracy to democracy unlike any other in Europe.

Sir Christopher Munro Clark is an Australian historian living in the United Kingdom and Germany. He is the twenty-second Regius Professor of History at the University of Cambridge. In 2015, he was knighted for his services to Anglo-German relations.

David Gordon Blackbourn is Cornelius Vanderbilt distinguished chair of history at Vanderbilt University, where he teaches modern German and European history. Prior to arriving at Vanderbilt, Blackbourn was Coolidge Professor of history at Harvard University.

Geoffrey Howard [Geoff] Eley is a British-born historian of Germany. He studied history at Balliol College, Oxford, and received his PhD from the University of Sussex in 1974. He has taught at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor in the Department of History since 1979 and the Department of German Studies since 1997. He now serves as the Karl Pohrt Distinguished University Professor of Contemporary History at Michigan.

Hermann Baumgarten was a German historian and a political publicist whose work had a major impact on liberalism during the unification of Germany. Baumgarten's philosophy also created a significant political impression on Max Weber, an influential social theorist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Bielefeld School is a group of German historians based originally at Bielefeld University who promote social history and political history using quantification and the methods of political science and sociology. The leaders include Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Jürgen Kocka and Reinhart Koselleck. Instead of emphasizing the personalities of great historical leaders, as in the conventional approach, it concentrates on socio-cultural developments. History as "historical social science" has mainly been explored in the context of studies of German society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The movement has published the scholarly journal Geschichte und Gesellschaft: Zeitschrift fur Historische Sozialwissenschaft since 1975.

Thomas Nipperdey was a German historian best known for his monumental and exhaustive studies of Germany from 1800 to 1918. As a critical follower of Leopold von Ranke's famous ideal of writing "history exactly as it happened," Nipperdey sought to explain the interconnectedness of political, social and cultural developments, while avoiding partisanship and rejecting moralistic efforts to see German history before 1933 only in the light of Nazism.

The historian John A. Davis said in 2005, "Everyone, it seems, is busy rethinking, revisioning, revisiting, remaking, remapping or demythologizing the Risorgimento. However, it is not the Risorgimento that is being revisited but the changing images that have made it the potent founding myth of the Italian nation for successive generations of Italians." In the 20th century, and especially since the end of the Second World War, the received interpretation of Italian unification, the Risorgimento, has become the object of historical revisionism. The justifications offered for unification, the methods employed to realise it and the benefits supposedly accruing to unified Italy are frequent targets of the revisionists. Some schools have called the Risorgimento an imperialist or colonialist venture imposed by Savoy.

Lothar Gall is a German historian known as "one of German liberalism's primary historians". He was professor of history at Goethe University Frankfurt from 1975 until his retirement in 2005.

The historiography of Germany deals with the manner in which historians have depicted, analyzed and debated the history of Germany. It also covers the popular memory of critical historical events, ideas and leaders, as well as the depiction of those events in museums, monuments, reenactments, pageants and historic sites, and the editing of historical documents.