Related Research Articles

Sudovian was a West Baltic language of Northeastern Europe. Sudovian was closely related to Old Prussian. It was formerly spoken southwest of the Neman river in what is now Lithuania, east of Galindia and in the north of Yotvingia, and by exiles in East Prussia.

Lithuanian is an East Baltic language belonging to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is the language of Lithuanians and the official language of Lithuania as well as one of the official languages of the European Union. There are approximately 2.8 million native Lithuanian speakers in Lithuania and about 1 million speakers elsewhere. Around half a million inhabitants of Lithuania of non-Lithuanian background speak Lithuanian daily as a second language.

The river Neris or Vilija rises in northern Belarus. It flows westward, passing through Vilnius and in the south-centre of that country it flows into the Nemunas (Neman) from the right bank, at Kaunas, as its main tributary. Its length is 510 km (320 mi).

Yotvingians were a Western Baltic people who were closely tied to the Old Prussians. The linguist Petras Būtėnas asserts that they were closest to the Lithuanians. The Yotvingians contributed to the formation of the Lithuanian state.

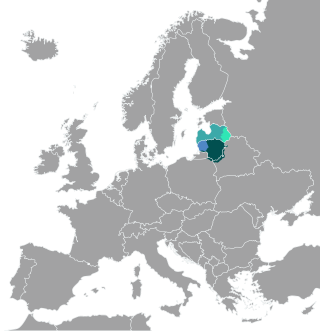

The East Baltic languages are a group of languages that along with the extinct West Baltic languages belong to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family. The East Baltic branch primarily consists primarily of two extant languages—Latvian and Lithuanian. Occasionally, Latgalian and Samogitian are viewed as distinct languages, though they are traditionally regarded as dialects. It also includes now-extinct Selonian, Semigallian, and possibly Old Curonian.

Proto-Baltic is the unattested, reconstructed ancestral proto-language of all Baltic languages. It is not attested in writing, but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method by gathering the collected data on attested Baltic and other Indo-European languages. It represents the common Baltic speech that approximately was spoken between the 3rd millennium BC and ca. 5th century BC, after which it began dividing into West and East Baltic languages. Proto-Baltic is thought to have been a fusional language and is associated with the Corded Ware and Trzciniec cultures.

Darius and Girėnas stadium is a multi-use stadium in Kaunas, Lithuania. With a seating capacity of 15,026, it is the largest stadium in Lithuania and the Baltic states. Located in the Ąžuolynas park in Žaliakalnis district, it serves as a venue for football matches, athletic competitions, and other events. In 1998, the stadium was renovated according to UEFA regulations, and in 2005, it was modernised with the installation of the biggest stadium television screen in the Baltic states. The latest renovation started in 2018 and ended in 2022. During the sporting season, at least 50 events are held here annually.

Zigmas Zinkevičius was a Lithuanian academician, Baltist, linguist, linguistic historian, dialectologist, politician, and the former Minister of Education and Science of Lithuania (1996–1998). Zinkevičius authored over a hundred books, including the popular six-volume "History of the Lithuanian language" (1984–1994), and over a thousand articles, both in Lithuanian and other languages. He was an academician of the Lithuanian Catholic Academy of Science since 1991 and a full member of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences from 1990 to 2011, when he became an emeritus member.

Vilnija is a Lithuanian cultural and political organization, created to promote and preserve Lithuanian culture in Vilnius region, the Lithuanian name after which the organization is named. The organization has been described as nationalist, extremist, and anti-Polish.

The first known record of the name of Lithuania recorded in the Quedlinburg Chronicle in a 9 March 1009 story of Saint Bruno. The Chronicle recorded in the form Litua. Although it is clear the name originated from a Baltic language, scholars still debate the meaning of the word.

Viktoras Biržiška was a Lithuanian mathematician, engineer, journalist, and encyclopedist of noble extraction. His brothers were Mykolas Biržiška and Vaclovas Biržiška.

A Lithuanian personal name, as in most European cultures, consists of two main elements: the given name followed by the family name. The usage of personal names in Lithuania is generally governed by three major factors: civil law, canon law, and tradition. Lithuanian names always follow the rules of the Lithuanian language. Lithuanian male names have preserved the Indo-European masculine endings. These gendered endings are preserved even for foreign names.

The Science and Encyclopaedia Publishing Centre is a Lithuanian publishing house that specializes in encyclopedias, reference works, and dictionaries. The Institute, headquartered in Vilnius, is supported by the Lithuanian Republic's Ministry of Education and Science.

Viktoras Petkus was a Lithuanian political activist and Soviet dissident. He was a founding member of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group in 1976 which set out to document violations of human rights in the Soviet Union. For various anti-Soviet activities, Petkus was imprisoned three times in various prisons and Gulag camps by the Soviet authorities.

Jūratė Regina Statkutė de Rosales was a Lithuanian-born Venezuelan journalist and amateur historian. She published studies in Venezuela, Spain, the United States, and Lithuania in which she claims that the Goths were not a Germanic but a Baltic people.

Aleksandras Mykolas Račkus was a Lithuanian physician and an active member of the Lithuanian American community known for his numismatic and other collections. In 1917, he co-founded the Lithuanian Society of Numismatics and History in Chicago. In 1935, his and the society's collections were acquired by Lithuania and are held by the M. K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum. He then restarted a Lithuania-themed collection which was acquired by the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture in 1965. A collection of various documents related to Lithuanian Americans and their organizations and societies is kept by the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania.

Aleksandras Fromas known by his pen name Gužutis (1822–1900) was a Lithuanian writer, one of the first authors of Lithuanian plays and dramas.

Česlovas Gedgaudas was a Lithuanian diplomat, translator, polyglot, and amateur historian. He is best known for his pseudohistorical book In the Search for Our Past, in which he promoted the claims of Jurate Rosales and Aleksandras Račkus that the Goths and Vandals were Baltic peoples, and not Germanic or Slavic.

Compendium Grammaticæ Lithvanicæ is a prescriptive printed grammar of the Lithuanian language, which was one of the first attempts to standardize the Lithuanian language. The grammar was intended for pastors who knew little or no Lithuanian so that they could learn the language and communicate with their Lithuanian-speaking parishioners.

References

- ↑ Karpavičienė, Dalia (2010). "Apie Lietuvą, kuriai daugiau nei tūkstantis metų (About Lithuania, which is more than a millennium old)". Šiaulių kraštas.

- ↑ Butkus, Alvydas; Lanza, Stefano M. (2012). "Kaip baltai tampa gotais (How Balts become Goths)". alkas.lt.

- ↑ Krušinskas, Leopoldas (2018). "Pristatyta papildyto ir pataisyto leidimo knyga "Mūsų praeities beieškant" (Updated and edited version of "Mūsų praeities beieškant" presented)". ekspertai.eu.

- ↑ Gedgaudas, Česlovas (1994). Mūsų praeities beieškant. Kaunas: Aušra. p. 68. ISBN 978-9986407119.

- ↑ Samoškaitė, Edita (2010). "Istorikas: gėda Lietuvai, kuri savo karalius nužemintai vadina kunigaikščiais (Historian: Shame for Lithuania, which refuses to call its Grand Dukes "Kings")". Delfi.

- ↑ Šeibak, Loreta (2008). ""Sarmata", kad Lietuva nesivadina Sarmatija (Shame, that Lithuania does not call itself Sarmatia)". Klaipėdos diena.

- ↑ Girkus, Romualdas; Lukoševičius, Viktoras (2010). "Reflection of "European Sarmatia" in Early Cartography". Geodesy and Cartography. Vilnius Gediminas Technical University. doi:10.3846/gc.2010.20. S2CID 129855390.

- ↑ "Sarmatai". www.sarmatas.lt (in Lithuanian). 27 January 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ↑ "Sarmatas.lt publikacijoje – ir vėl apstu melagingos informacijos: fantazuoja, kad pandemijos nėra, o PGR testai meluoja (Sarmatas.lt is again full of fake news: fantasizes that COVID does not exist, claims that PGR tests are lying)". Delfi.

- ↑ "Sarmatas.lt publikacijoje gausu klaidinančios informacijos apie translyčius (Sarmatas.lt is full of misleading information about transgender people)". Gayline.lt. 2021.

- ↑ Gedgaudas, Česlovas (1994). Mūsų praeities beieškant. Kaunas: Aušra. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-9986407119.

- ↑ Gedgaudas, Česlovas (1994). Mūsų praeities beieškant. Kaunas: Aušra. p. 18. ISBN 978-9986407119.

- ↑ Gedgaudas, Česlovas (1994). Mūsų praeities beieškant. Kaunas: Aušra. p. 327. ISBN 978-9986407119.

- ↑ Gedgaudas, Česlovas (1994). Mūsų praeities beieškant. Kaunas: Aušra. pp. 3–13. ISBN 978-9986407119.

- ↑ Zinkevičius, Zigmas (2011). "Jūratė Statkutė de Rosales ir gotų istorija". Lituanistica (in Lithuanian). 4 (86): 474. ISSN 2424-4716.

- ↑ Girkus, Romualdas; Lukoševičius, Viktoras (2010). "Reflection of "European Sarmatia" in Early Cartography". Geodesy and Cartography. Vilnius Gediminas Technical University. doi:10.3846/gc.2010.20. S2CID 129855390.

- ↑ Zinkevičius, Zigmas (2011). Jūratė Statkutė de Rosales ir gotų istorija. Vol. 4. Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. pp. 472–475.

- ↑ Matulis, Rimantas (2016). "Ptolemėjo geografija ir baltų tautos (Ptolemy's geography and the Baltic nations)". alkas.lt.