Arianism is a Christological doctrine considered heretical by all modern mainstream branches of Christianity. It is first attributed to Arius, a Christian presbyter who preached and studied in Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God the Father with the difference that the Son of God did not always exist but was begotten/made before time by God the Father; therefore, Jesus was not coeternal with God the Father, but nonetheless Jesus began to exist outside time.

Athanasius I of Alexandria, also called Athanasius the Great, Athanasius the Confessor, or, among Coptic Christians, Athanasius the Apostolic, was a Christian theologian and the 20th pope of Alexandria. His intermittent episcopacy spanned 45 years, of which over 17 encompassed five exiles, when he was replaced on the order of four different Roman emperors. Athanasius was a Church Father, the chief proponent of Trinitarianism against Arianism, and a noted Egyptian Christian leader of the fourth century.

Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a pivotal role in elevating the status of Christianity in Rome, decriminalizing Christian practice and ceasing Christian persecution in a period referred to as the Constantinian shift. This initiated the Christianization of the Roman Empire. Constantine is associated with the religiopolitical ideology known as Caesaropapism, which epitomizes the unity of church and state. He founded the city of Constantinople and made it the capital of the Empire, which remained so for over a millennium.

Eusebius of Caesarea, also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a Greek Syro-Palestinian historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima in the Roman province of Syria Palaestina.

Eusebius of Nicomedia was an Arian priest who baptized Constantine the Great on his deathbed in 337. A fifth-century legend evolved that Pope Sylvester I was the one to baptize Constantine, but this is dismissed by scholars as a forgery 'to amend the historical memory of the Arian baptism that the emperor received at the end of his life, and instead to attribute an unequivocally orthodox baptism to him.' He was a bishop of Berytus in Phoenicia. He was later made the bishop of Nicomedia, where the Imperial court resided. He lived finally in Constantinople from 338 up to his death.

The First Council of Nicaea was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

The First Council of Constantinople was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople in AD 381 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I. This second ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church through an assembly representing all of Christendom, except for the Western Church, confirmed the Nicene Creed, expanding the doctrine thereof to produce the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, and dealt with sundry other matters. It met from May to July 381 in the Church of Hagia Irene and was affirmed as ecumenical in 451 at the Council of Chalcedon.

Arius was a Cyrenaic presbyter and ascetic. He has been traditionally regarded as the founder of Arianism, which holds that Jesus Christ was not coeternal with God the Father, but was rather created before time. Arian theology and its doctrine regarding the nature of the Godhead held in common a belief in subordinationism with most Christian theologians of the 3rd century, with the notable exception of Athanasius of Alexandria.

The Edict of Milan was the February, AD 313 agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Emperor Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, met in Mediolanum and, among other things, agreed to change policies towards Christians following the edict of toleration issued by Emperor Galerius two years earlier in Serdica. The Edict of Milan gave Christianity legal status and a reprieve from persecution but did not make it the state church of the Roman Empire, which occurred in AD 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica, when Nicene Christianity received normative status.

Hosius of Corduba, also known as Osius or Ossius, was a bishop of Corduba and an important and prominent advocate for Homoousion Christianity in the Arian controversy that divided the early Christianity.

The Acacians, or perhaps better described as the Homoians or Homoeans, were a non-Nicene branch of Christianity that dominated the church during much of the fourth-century Arian Controversy. They declared that the Son was similar to God the Father, without reference to substance (essence). Homoians played a major role in the Christianization of the Goths in the Danubian provinces of the Roman Empire.

In 294 AD, Sirmium was proclaimed one of four capitals of the Roman Empire. The Councils of Sirmium were the five episcopal councils held in Sirmium in 347, 351, 357, 358 and finally in 375 or 378. In the traditional account of the Arian Controversy, the Western Church always defended the Nicene Creed. However, at the third council in 357—the most important of these councils—the Western bishops of the Christian church produced an 'Arian' Creed, known as the Second Sirmian Creed. At least two of the other councils also dealt primarily with the Arian controversy. All of these councils were held under the rule of Constantius II, who was eager to unite the church within the framework of the Eusebian Homoianism that was so influential in the east.

During the reign of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great (306–337 AD), Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Historians remain uncertain about Constantine's reasons for favoring Christianity, and theologians and historians have often argued about which form of early Christianity he subscribed to. There is no consensus among scholars as to whether he adopted his mother Helena's Christianity in his youth, or, as claimed by Eusebius of Caesarea, encouraged her to convert to the faith he had adopted.

The Arian controversy was a series of Christian disputes about the nature of Christ that began with a dispute between Arius and Athanasius of Alexandria, two Christian theologians from Alexandria, Egypt. The most important of these controversies concerned the relationship between the substance of God the Father and the substance of His Son.

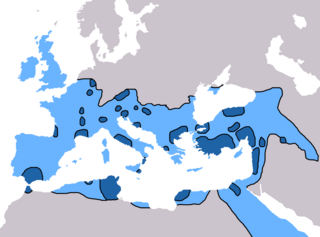

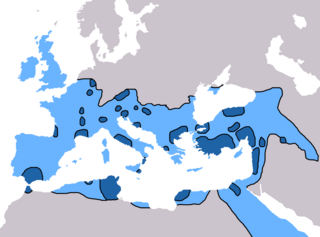

Christianity in the 4th century was dominated in its early stage by Constantine the Great and the First Council of Nicaea of 325, which was the beginning of the period of the First seven Ecumenical Councils (325–787), and in its late stage by the Edict of Thessalonica of 380, which made Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire.

The Edict of Thessalonica, issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire. It condemned other Christian creeds such as Arianism as heresies of "foolish madmen," and authorized their punishment.

Christianity in late antiquity traces Christianity during the Christian Roman Empire — the period from the rise of Christianity under Emperor Constantine, until the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The end-date of this period varies because the transition to the sub-Roman period occurred gradually and at different times in different areas. One may generally date late ancient Christianity as lasting to the late 6th century and the re-conquests under Justinian of the Byzantine Empire, though a more traditional end-date is 476, the year in which Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus, traditionally considered the last western emperor.

Constantine the Great's (272–337) relationship with the four Bishops of Rome during his reign is an important component of the history of the Papacy, and more generally the history of the Catholic Church.

In the year before the Council of Constantinople in 381, the Trinitarian version of Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians as the Roman Empire's state religion. Historians refer to the Nicene church associated with emperors in a variety of ways: as the catholic church, the orthodox church, the imperial church, the Roman church, or the Byzantine church, although some of those terms are also used for wider communions extending outside the Roman Empire. The Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Church all claim to stand in continuity from the Nicene church to which Theodosius granted recognition.

The Religious policies of Constantine the Great have been called "ambiguous and elusive." Born in 273 during the Crisis of the Third Century, Constantine the Great was thirty at the time of the Great Persecution. He saw his father become Augustus of the West and then shortly die. Constantine spent his life in the military warring with much of his extended family, and converted to Christianity sometime around 40 years of age. His religious policies, formed from these experiences, comprised increasing toleration of Christianity, limited regulations against Roman polytheism with toleration, participation in resolving religious disputes such as schism with the Donatists, and the calling of councils including the Council of Nicaea concerning Arianism. John Kaye characterizes the conversion of Constantine, and the Council of Nicea that Constantine called, as two of the most important things to ever happen to the Christian church.