The 20 July plot was a failed attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler, the chancellor and leader of National Socialist Germany, and subsequently to overthrow the National Socialist regime on 20 July 1944. The plotters were part of the German resistance, mainly composed of Wehrmacht officers. The leader of the conspiracy, Claus von Stauffenberg, planned to kill Hitler by detonating an explosive hidden in a briefcase. However, due to the location of the bomb at the time of detonation, the blast only dealt Hitler minor injuries. The planners' subsequent coup attempt also failed and resulted in a purge of the Wehrmacht.

Friedrich Adam von Trott zu Solz was a German lawyer and diplomat who was involved in the conservative resistance to Nazism. A declared opponent of the Nazi regime from the beginning, he actively participated in the Kreisau Circle of Helmuth James Graf von Moltke and Peter Yorck von Wartenburg. Together with Claus von Stauffenberg and Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, he conspired in the 20 July plot and was supposed to have been appointed Secretary of State in the Foreign Office and lead negotiator with the Western Allies if the plot had succeeded.

Carl Friedrich Goerdeler was a German conservative politician, monarchist, executive, economist, civil servant and opponent of the Nazi regime. He opposed some anti-Jewish policies while he held office and was opposed to the Holocaust.

Sir Ian Kershaw is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's foremost experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is particularly noted for his biographies of Hitler.

The Historikerstreit was a dispute in the late 1980s in West Germany between conservative and left-of-center academics and other intellectuals about how to incorporate Nazi Germany and the Holocaust into German historiography, and more generally into the German people's view of themselves. The dispute was initiated with the Bitburg controversy, which related to a commemorative service at a German military cemetery where members of the Waffen-SS were buried. The service was attended by President of the United States Ronald Reagan, who had been invited by the West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. The Bitburg ceremony was widely interpreted in Germany as the beginning of the "normalization" of the nation's Nazi past, and inspired a slew of criticisms and defenses that made up the initiating arguments of the Historikerstreit. The dispute quickly outgrew the initial context of the Bitburg controversy, however, and became a series of broader historiographic, political, and critical debates about how the episode of the Holocaust should be understood in Germany's history and identity.

Gerhard Georg Bernhard Ritter was a German historian who served as a professor of history at the University of Freiburg from 1925 to 1956. He studied under Professor Hermann Oncken. A Lutheran, he first became well known for his 1925 biography of Martin Luther and hagiographic portrayal of Prussia. A member of the German People's Party during the Weimar Republic, he was a lifelong monarchist and remained sympathetic to the political system of the defunct German Empire.

Hans Mommsen was a German historian, known for his studies in German social history, for his functionalist interpretation of the Third Reich, and especially for arguing that Adolf Hitler was a weak dictator. Descended from Nobel Prize-winning historian Theodor Mommsen, he was a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

The functionalism–intentionalism debate is a historiographical debate about the reasons for the Holocaust as well as most aspects of the Third Reich, such as foreign policy. It essentially centres on two questions:

Martin Broszat was a German historian specializing in modern German social history. As director of the Institut für Zeitgeschichte in Munich from 1972 until his death, he became known as one of the world's most eminent scholars of Nazi Germany.

Ernst Nolte was a German historian and philosopher. Nolte's major interest was the comparative studies of fascism and communism. Originally trained in philosophy, he was professor emeritus of modern history at the Free University of Berlin, where he taught from 1973 until his 1991 retirement. He was previously a professor at the University of Marburg from 1965 to 1973. He was best known for his seminal work Fascism in Its Epoch, which received widespread acclaim when it was published in 1963. Nolte was a prominent conservative academic from the early 1960s and was involved in many controversies related to the interpretation of the history of fascism and communism, including the Historikerstreit in the late 1980s. In later years, Nolte focused on Islamism and "Islamic fascism".

Saul Friedländer is a Czech-Jewish-born historian and a professor emeritus of history at UCLA.

Detlev Julio K. Peukert was a German historian, noted for his studies of the relationship between what he called the "spirit of science" and the Holocaust and in social history and the Weimar Republic. Peukert taught modern history at the University of Essen and served as director of the Research Institute for the History of the Nazi Period. Peukert was a member of the German Communist Party until 1978, when he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany. A politically engaged historian, Peukert was known for his unconventional take on modern German history, and in an obituary, the British historian Richard Bessel wrote that it was a major loss that Peukert had died at the age of 39 as a result of AIDS.

Many individuals and groups in Germany that were opposed to the Nazi regime engaged in resistance, including assassination attempts on Adolf Hitler or by overthrowing his regime.

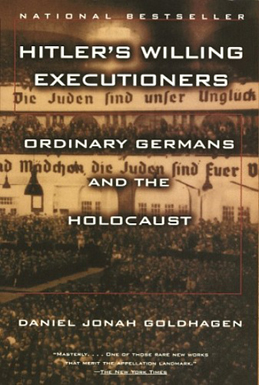

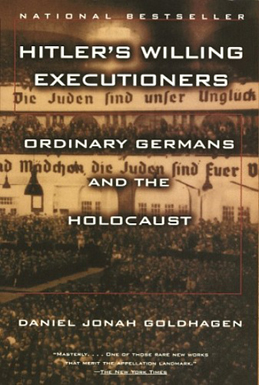

Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust is a 1996 book by American writer Daniel Goldhagen, in which he argues that the vast majority of ordinary Germans were "willing executioners" in the Holocaust because of a unique and virulent "eliminationist antisemitism" in German political culture which had developed in the preceding centuries. Goldhagen argues that eliminationist antisemitism was the cornerstone of German national identity, was unique to Germany, and because of it ordinary German conscripts killed Jews willingly. Goldhagen asserts that this mentality grew out of medieval attitudes rooted in religion and was later secularized.

Hans Christian Gerlach is professor of Modern History at the University of Bern. Gerlach is also Associate Editor of the Journal of Genocide Research and author of multiple books dealing with the Hunger Plan, the Holocaust, and genocide.

Popes Pius XI (1922–1939) and Pius XII (1939–1958) led the Catholic Church during the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. Around a third of Germans were Catholic in the 1930s, most of them lived in Southern Germany; Protestants dominated the north. The Catholic Church in Germany opposed the Nazi Party, and in the 1933 elections, the proportion of Catholics who voted for the Nazi Party was lower than the national average. Nevertheless, the Catholic-aligned Centre Party voted for the Enabling Act of 1933, which gave Adolf Hitler additional domestic powers to suppress political opponents as Chancellor of Germany. President Paul Von Hindenburg continued to serve as Commander and Chief and he also continued to be responsible for the negotiation of international treaties until his death on 2 August 1934.

Fascism in Its Epoch, also known in English as The Three Faces of Fascism, is a 1963 book by historian and philosopher Ernst Nolte. It is widely regarded as his magnum opus and a seminal work on the history of fascism.

At the outbreak of World War II, the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) had some 1700 members in Nazi Germany, divided into three provinces: Eastern, Lower and Upper Germany. Nazi leaders had some admiration for the discipline of the Jesuit order, but opposed its principles. Of the 152 Jesuits murdered by the Nazis across Europe, 27 died in captivity or its results, and 43 in the concentration camps.

The historiography of Adolf Hitler deals with the academic studies of Adolf Hitler from the 1930s to the present. In 1998, a German editor said there were 120,000 studies of Hitler and Nazi Germany. Since then many more have appeared, with many of them decisively shaping the historiography regarding Hitler.

During a speech at the Reichstag on 30 January 1939, Adolf Hitler threatened "the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe" in the event of war:

If international finance Jewry inside and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, the result will be not the Bolshevization of the earth and thereby the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.