Captain Robert Falcon Scott was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova expedition of 1910–13.

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

The Beardmore Glacier in Antarctica is one of the largest valley glaciers in the world, being 200 km (125 mi) long and having a width of 40 km (25 mi). It descends about 2,200 m (7,200 ft) from the Antarctic Plateau to the Ross Ice Shelf and is bordered by the Commonwealth Range of the Queen Maud Mountains on the eastern side and the Queen Alexandra Range of the Central Transantarctic Mountains on the western. Its mouth is east of the Lennox-King Glacier. It is northwest of the Ramsey Glacier.

Scott of the Antarctic is a 1948 British adventure film starring John Mills as Robert Falcon Scott in his ill-fated attempt to reach the South Pole. The film more or less faithfully recreates the events that befell the Terra Nova Expedition in 1912.

Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard was an English explorer of Antarctica. He was a member of the Terra Nova expedition and is acclaimed for his 1922 account of this expedition, The Worst Journey in the World.

Roland Huntford is an author, principally of biographies of Polar explorers.

Thomas Crean was an Irish seaman and Antarctic explorer who was awarded the Albert Medal for Lifesaving (AM).

Henry Robertson Bowers was one of Robert Falcon Scott's polar party on the ill-fated Terra Nova expedition of 1910–1913, all of whom died during their return from the South Pole.

William Lashly was a Royal Navy seaman who served as lead stoker on both the Discovery expedition and the Terra Nova expedition to Antarctica, for which he was awarded the Polar Medal. Lashly was also recognised with the Albert Medal for playing a key role in saving the life of a comrade on the second of the two expeditions.

The DiscoveryExpedition of 1901–1904, known officially as the British National Antarctic Expedition, was the first official British exploration of the Antarctic regions since the voyage of James Clark Ross sixty years earlier (1839–1843). Organized on a large scale under a joint committee of the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), the new expedition carried out scientific research and geographical exploration in what was then largely an untouched continent. It launched the Antarctic careers of many who would become leading figures in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, including Robert Falcon Scott who led the expedition, Ernest Shackleton, Edward Wilson, Frank Wild, Tom Crean and William Lashly.

The NimrodExpedition of 1907–1909, otherwise known as the British Antarctic Expedition, was the first of three expeditions to the Antarctic led by Ernest Shackleton and his second time to the Continent. Its main target, among a range of geographical and scientific objectives, was to be first to reach the South Pole. This was not attained, but the expedition's southern march reached a Farthest South latitude of 88° 23' S, just 97.5 nautical miles from the pole. This was by far the longest southern polar journey to that date and a record convergence on either Pole. A separate group led by Welsh Australian geology professor Edgeworth David reached the estimated location of the South magnetic pole, and the expedition also achieved the first ascent of Mount Erebus, Antarctica's second highest volcano.

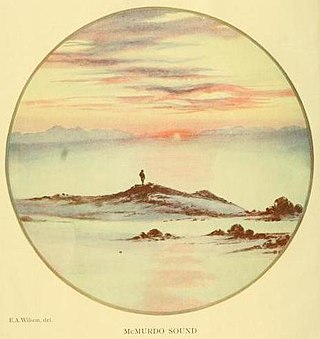

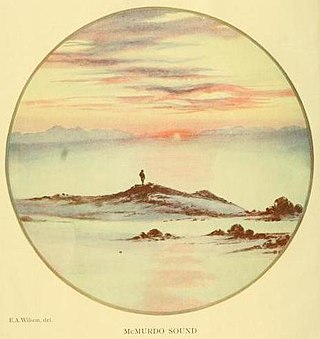

The Terra NovaExpedition, officially the British Antarctic Expedition, was an expedition to Antarctica which took place between 1910 and 1913. Led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott, the expedition had various scientific and geographical objectives. Scott wished to continue the scientific work that he had begun when leading the Discovery Expedition from 1901 to 1904, and wanted to be the first to reach the geographic South Pole.

The Worst Journey in the World is a 1922 memoir by Apsley Cherry-Garrard of Robert Falcon Scott's Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole in 1910–1913. It has earned wide praise for its frank treatment of the difficulties of the expedition, the causes of its disastrous outcome, and the meaning of human suffering under extreme conditions.

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was an era in the exploration of the continent of Antarctica which began at the end of the 19th century, and ended after the First World War; the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition of 1921–1922 is often cited by historians as the dividing line between the "Heroic" and "Mechanical" ages.

The Last Place on Earth is a 1985 Central Television seven-part serial, written by Trevor Griffiths based on the book Scott and Amundsen by Roland Huntford. The book is an exploration of the expeditions of Captain Robert F. Scott and his Norwegian rival in polar exploration, Roald Amundsen in their attempts to reach the South Pole.

Manhauling or man-hauling is the pulling forward of sledges, trucks or other load-carrying vehicles by human power unaided by animals or machines. The term is used primarily in connection with travel over snow and ice, and was common during Arctic and Antarctic expeditions before the days of modern motorised traction.

The first ever expedition to reach the Geographic South Pole was led by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. He and four other crew members made it to the geographical south pole on 14 December 1911, which would prove to be five weeks ahead of the competitive British party led by Robert Falcon Scott as part of the Terra Nova Expedition. Amundsen and his team returned safely to their base, and about a year later heard that Scott and his four companions had perished on their return journey.

Edward Leicester Atkinson, was a Royal Navy surgeon and Antarctic explorer who was a member of the scientific staff of Captain Scott's Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13. He was in command of the expedition's base at Cape Evans for much of 1912, and led the party which found the tent containing the bodies of Scott, "Birdie" Bowers and Edward Wilson. Atkinson was subsequently associated with two controversies: that relating to Scott's orders concerning the use of dogs, and that relating to the possible incidence of scurvy in the polar party. He is commemorated by the Atkinson Cliffs on the northern coast of Victoria Land, Antarctica, at 71°18′S168°55′E.

Farthest South refers to the most southerly latitudes reached by explorers before the first successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911.

Between December 1911 and January 1912, both Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott reached the South Pole within five weeks of each other. But while Scott and his four companions died on the return journey, Amundsen's party managed to reach the geographic south pole first and subsequently return to their base camp at Framheim without loss of human life, suggesting that they were better prepared for the expedition. The contrasting fates of the two teams seeking the same prize at the same time invites comparison.