An iceberg is a piece of fresh water ice more than 15 meters long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". Much of an iceberg is below the water's surface, which led to the expression "tip of the iceberg" to illustrate a small part of a larger unseen issue. Icebergs are considered a serious maritime hazard.

The climate of Antarctica is the coldest on Earth. The continent is also extremely dry, averaging 166 mm (6.5 in) of precipitation per year. Snow rarely melts on most parts of the continent, and, after being compressed, becomes the glacier ice that makes up the ice sheet. Weather fronts rarely penetrate far into the continent, because of the katabatic winds. Most of Antarctica has an ice-cap climate with extremely cold and dry weather.

An ice shelf is a large platform of glacial ice floating on the ocean, fed by one or multiple tributary glaciers. Ice shelves form along coastlines where the ice thickness is insufficient to displace the more dense surrounding ocean water. The boundary between the ice shelf (floating) and grounded ice is referred to as the grounding line; the boundary between the ice shelf and the open ocean is the ice front or calving front.

The Amundsen Sea is an arm of the Southern Ocean off Marie Byrd Land in western Antarctica. It lies between Cape Flying Fish to the east and Cape Dart on Siple Island to the west. Cape Flying Fish marks the boundary between the Amundsen Sea and the Bellingshausen Sea. West of Cape Dart there is no named marginal sea of the Southern Ocean between the Amundsen and Ross Seas. The Norwegian expedition of 1928–1929 under Captain Nils Larsen named the body of water for the Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen while exploring this area in February 1929.

The Larsen Ice Shelf is a long ice shelf in the northwest part of the Weddell Sea, extending along the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula from Cape Longing to Smith Peninsula. It is named after Captain Carl Anton Larsen, the master of the Norwegian whaling vessel Jason, who sailed along the ice front as far as 68°10' South during December 1893. In finer detail, the Larsen Ice Shelf is a series of shelves that occupy distinct embayments along the coast. From north to south, the segments are called Larsen A, Larsen B, and Larsen C by researchers who work in the area. Further south, Larsen D and the much smaller Larsen E, F and G are also named.

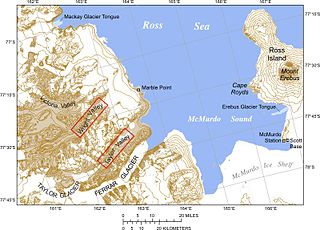

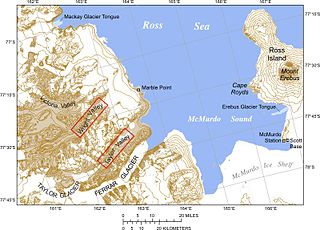

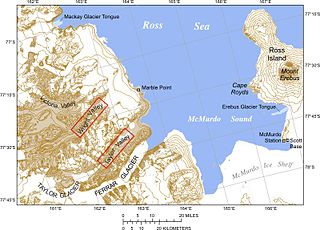

The McMurdo Sound is a sound in Antarctica, known as the southernmost passable body of water in the world, located approximately 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) from the South Pole.

Marie Byrd Land (MBL) is an unclaimed region of Antarctica. With an area of 1,610,000 km2 (620,000 sq mi), it is the largest unclaimed territory on Earth. It was named after the wife of American naval officer Richard E. Byrd, who explored the region in the early 20th century.

The Bay of Whales was a natural ice harbour, or iceport, indenting the front of the Ross Ice Shelf just north of Roosevelt Island, Antarctica, at the southernmost point of the world's ocean. While the Ross Sea stretches considerably further south – encompassing the Gould Coast, located around 320 kilometres from the South Pole – the majority of this expanse is covered by the Ross Ice Shelf, rather than open sea.

The Leverett Glacier is about 50 nautical miles (90 km) long and 3 to 4 nautical miles wide, flowing from the Antarctic Plateau to the south end of the Ross Ice Shelf through the Queen Maud Mountains. It is an important part of the South Pole Traverse from McMurdo Station to the Admundson–Scott South Pole Station, providing a route for tractors to climb from the ice shelf through the Transantarctic Mountains to the polar plateau.

The Brunt Ice Shelf borders the Antarctic coast of Coats Land between Dawson-Lambton Glacier and Stancomb-Wills Glacier Tongue. It was named by the UK Antarctic Place-names Committee after David Brunt, British meteorologist, Physical Secretary of the Royal Society, 1948–57, who was responsible for the initiation of the Royal Society Expedition to this ice shelf in 1955.

Iceberg B-15 was the largest recorded iceberg by area. It measured around 295 by 37 kilometres, with a surface area of 11,000 square kilometres, about the size of the island of Jamaica. Calved from the Ross Ice Shelf of Antarctica in March 2000, Iceberg B-15 broke up into smaller icebergs, the largest of which was named Iceberg B-15-A. In 2003, B-15A drifted away from Ross Island into the Ross Sea and headed north, eventually breaking up into several smaller icebergs in October 2005. In 2018, a large piece of the original iceberg was steadily moving northward, located between the Falkland Islands and South Georgia Island. As of August 2023, the U.S. National Ice Center (USNIC) still lists one extant piece of B-15 that meets the minimum threshold for tracking. This iceberg, B-15AB, measures 20 km × 7 km ; it is currently grounded off the coast of Antarctica in the western sector of the Amery region.

The Drygalski Ice Tongue, Drygalski Barrier, or Drygalski Glacier Tongue is a glacier in Antarctica, on the Scott Coast, in the northern McMurdo Sound of Ross Dependency, 240 kilometres (150 mi) north of Ross Island. The Drygalski Ice Tongue is stable by the standards of Antarctica's icefloes, and stretches 70 kilometres (43 mi) out to sea from the David Glacier, reaching the sea from a valley in the Prince Albert Mountains of Victoria Land. The Drygalski Ice Tongue ranges from 14 to 24 kilometres wide.

The Amery Ice Shelf is a broad ice shelf in Antarctica at the head of Prydz Bay between the Lars Christensen Coast and Ingrid Christensen Coast. It is part of Mac. Robertson Land. The name "Cape Amery" was applied to a coastal angle mapped on 11 February 1931 by the British Australian New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) under Douglas Mawson. He named it for William Bankes Amery, a civil servant who represented the United Kingdom government in Australia (1925–28). The Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names interpreted this feature to be a portion of an ice shelf and, in 1947, applied the name Amery to the whole shelf.

Mertz Glacier is a heavily crevassed glacier in George V Coast of East Antarctica. It is the source of a glacial prominence that historically has extended northward into the Southern Ocean, the Mertz Glacial Tongue. It is named in honor of the Swiss explorer Xavier Mertz.

Pine Island Glacier (PIG) is a large ice stream, and the fastest melting glacier in Antarctica, responsible for about 25% of Antarctica's ice loss. The glacier ice streams flow west-northwest along the south side of the Hudson Mountains into Pine Island Bay, Amundsen Sea, Antarctica. It was mapped by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) from surveys and United States Navy (USN) air photos, 1960–66, and named by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (US-ACAN) in association with Pine Island Bay.

Thwaites Glacier is an unusually broad and vast Antarctic glacier located east of Mount Murphy, on the Walgreen Coast of Marie Byrd Land. It was initially sighted by polar researchers in 1940, mapped in 1959–1966 and officially named in 1967, after the late American glaciologist Fredrik T. Thwaites. The glacier flows into Pine Island Bay, part of the Amundsen Sea, at surface speeds which exceed 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) per year near its grounding line. Its fastest-flowing grounded ice is centered between 50 and 100 kilometres east of Mount Murphy. Like many other parts of the cryosphere, it has been adversely affected by climate change, and provides one of the more notable examples of the retreat of glaciers since 1850.

Totten Glacier is a large glacier draining a major portion of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, through the Budd Coast of Wilkes Land in the Australian Antarctic Territory. The catchment drained by the glacier is estimated at 538,000 km2 (208,000 sq mi), extending approximately 1,100 km (680 mi) into the interior and holds the potential to raise sea level by at least 3.5 m (11 ft). Totten drains northeastward from the continental ice but turns northwestward at the coast where it terminates in a prominent tongue close east of Cape Waldron. It was first delineated from aerial photographs taken by USN Operation Highjump (1946–47), and named by Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (US-ACAN) for George M. Totten, midshipman on USS Vincennes of the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–42), who assisted Lieutenant Charles Wilkes with correction of the survey data obtained by the expedition.

The Erebus Glacier Tongue is a mountain outlet glacier and the seaward extension of Erebus Glacier from Ross Island. It projects 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) into McMurdo Sound from the Ross Island coastline near Cape Evans, Antarctica. The glacier tongue varies in thickness from 50 metres (160 ft) at the snout to 300 metres (980 ft) at the point where it is grounded on the shoreline. Explorers from Robert F. Scott's Discovery Expedition (1901–1904) named and charted the glacier tongue.

Liu Yan is a Chinese Antarctic researcher best known for her work on iceberg calving. She is an associate professor of geography in the College of Global Change and Earth System Science (GCESS) and Polar Research Institute, Beijing Normal University.

Christina Hulbe is an American Antarctic researcher, and as of 2016 serves as professor and Dean of Surveying at the University of Otago in New Zealand. She was previously Chair of the Geology Department at Portland State University in Portland, Oregon. She leads the NZARI project to drill through the Ross Ice Shelf and is the namesake of the Hulbe glacier.