The German Empire, also referred to as Imperial Germany, the Second Reich or simply Germany, was the period of the German Reich from the unification of Germany in 1871 until the November Revolution in 1918, when the German Reich changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic.

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe, classical antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the modern era.

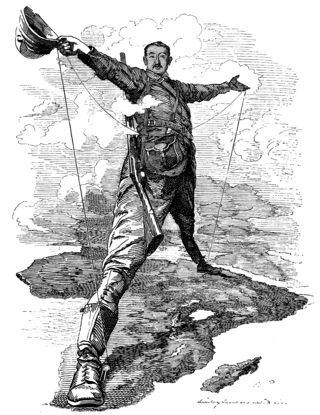

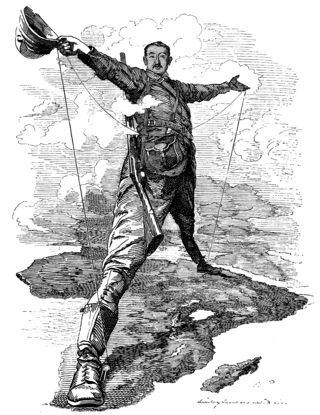

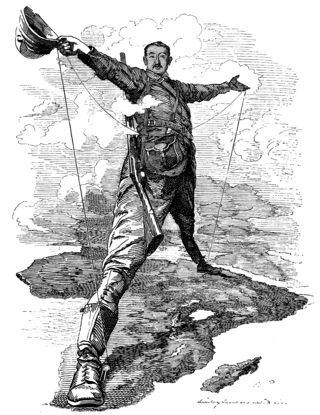

Imperialism is the practice, theory or attitude of maintaining or extending power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power and soft power. Imperialism focuses on establishing or maintaining hegemony and a more or less formal empire. While related to the concepts of colonialism, imperialism is a distinct concept that can apply to other forms of expansion and many forms of government.

Nationalism is an identity based belief system, an idea or social movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, especially with the aim of gaining and maintaining its sovereignty (self-governance) over its perceived homeland to create a nation-state. It holds that each nation should govern itself, free from outside interference (self-determination), that a nation is a natural and ideal basis for a polity, and that the nation is the only rightful source of political power. It further aims to build and maintain a single national identity, based on a combination of shared social characteristics such as culture, ethnicity, geographic location, language, politics, religion, traditions and belief in a shared singular history, and to promote national unity or solidarity. There are various definitions of a "nation", which leads to different types of nationalism. The two main divergent forms are ethnic nationalism and civic nationalism.

Superpower describes a sovereign state or supranational union that holds a dominant position characterized by the ability to exert influence and project power on a global scale. This is done through the combined means of economic, military, technological, political, and cultural strength as well as diplomatic and soft power influence. Traditionally, superpowers are preeminent among the great powers. While a great power state is capable of exerting its influence globally, superpowers are states so influential that no significant action can be taken by the global community without first considering the positions of the superpowers on the issue.

A world war is an international conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945), although some historians have also characterised other global conflicts as world wars, such as the Nine Years' War, the War of the Spanish Succession, the Seven Years' War, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, the Cold War, and the War on Terror.

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of overseas territorial acquisitions. At the time, states focused on building their empires with new technological advances and developments, expanding their territory through conquest, and exploiting the resources of the subjugated countries. During the era of New Imperialism, the European powers individually conquered almost all of Africa and parts of Asia. The new wave of imperialism reflected ongoing rivalries among the great powers, the economic desire for new resources and markets, and a "civilizing mission" ethos. Many of the colonies established during this era gained independence during the era of decolonization that followed World War II.

Pax Britannica was the period of relative peace between the great powers. During this time, the British Empire became the global hegemonic power, developed additional informal empire, and adopted the role of a "global policeman".

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the military and of the ideals of a professional military class and the "predominance of the armed forces in the administration or policy of the state".

The Concert of Europe was a general agreement among the great powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying for position and influence, the Concert was an extended period of relative peace and stability in Europe following the Wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars which had consumed the continent since the 1790s. There is considerable scholarly dispute over the exact nature and duration of the Concert. Some scholars argue that it fell apart nearly as soon as it began in the 1820s when the great powers disagreed over the handling of liberal revolts in Italy, while others argue that it lasted until the outbreak of World War I and others for points in between. For those arguing for a longer duration, there is generally agreement that the period after the Revolutions of 1848 and the Crimean War (1853–1856) represented a different phase with different dynamics than the earlier period.

Relations between France and Germany, or Franco-German relations form a part of the wider politics of Europe. The two countries have a long — and often contentious — relationship stretching back to the Middle Ages. Since 1945, they have largely reconciled, and since the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1958, they are among the founders and leading members of the European Communities and their successor the European Union.

The War of the Fourth Coalition was a war spanning 1806–1807 that saw a multinational coalition fight against Napoleon's French Empire, subsequently being defeated. The main coalition partners were Prussia and Russia with Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain also contributing. Excluding Prussia, some members of the coalition had previously been fighting France as part of the Third Coalition, and there was no intervening period of general peace. On 9 October 1806, Prussia declared war on France and joined a renewed coalition, fearing the rise in French power after the defeat of Austria and establishment of the French-sponsored Confederation of the Rhine in addition to having learned of French plans to cede Prussian-desired Hanover to Britain in exchange for peace. Prussia and Russia mobilized for a fresh campaign with France, massing troops in Saxony.

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500. From the 1990s, it is more common among historians to refer to the period after the Middle Ages and up to the 19th century as the early modern period. The modern period is today more often used for events from the 19th century until today. The time from the end of World War II (1945) can also be described as being part of contemporary history. The common definition of the modern period today is often associated with events like the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and the transition to nationalism towards the liberal international order.

French–German (Franco-German) enmity was the idea of unavoidably hostile relations and mutual revanchism between Germans and French people that arose in the 16th century and became popular with the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. It was an important factor in the unification of Germany, World War I, and ended after World War II, when under the influence of the Cold War, West Germany and France both became part of NATO and the European Coal and Steel Community.

The military history of Europe refers to the history of warfare on the European continent. From the beginning of the modern era to the second half of the 20th century, European militaries possessed a significant technological advantage, allowing its states to pursue policies of expansionism and colonization until the Cold War period. European militaries in between the fifteenth century and the modern period were able to conquer or subjugate almost every other nation in the world. Since the end of the Cold War, the European security environment has been characterized by structural dominance of the United States through its NATO commitments to the defense of Europe, as European states have sought to reap the 'peace dividend' occasioned by the end of the Cold War and reduce defense expenditures. European militaries now mostly undertake power projection missions outside the European continent. Recent military conflicts involving European nations include the 2001 War in Afghanistan, the 2003 War in Iraq, the 2011 NATO Campaign in Libya, and various other engagements in the Balkan and on the African continent. After 2014, the Russian annexation of Crimea and the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War prompted renewed scholarly interest into European military affairs. For further the context see History of Europe.

The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace, and the Course of History is a historico-philosophical work by Philip Bobbitt. It was first published in 2002 by Alfred Knopf in the US and Penguin in the UK.

"Second Thirty Years' War" is a periodization scheme sometimes used to encompass the wars in Europe from 1914 to 1945. Just as the Thirty Years' War of 1618 to 1648 was not a single war but a series of conflicts in varied times and locations, later organized and named by historians into a single period, the Second Thirty Years' War has been seen as a "European Civil War", fought over the problem of Germany and exacerbated by the new ideologies of fascism, Nazism and communism that came into power after World War I. The thesis of the Second Thirty Years' War is that World War I naturally led to World War II; in this framework, the latter is the inevitable result of the former, and thus they can be seen as a single conflict. Historians have criticized this thesis on the grounds that it excuses the actions of fascist and Nazi historical actors.

The European balance of power is a tenet in international relations that no single power should be allowed to achieve hegemony over a substantial part of Europe. During much of the Modern Age, the balance was achieved by having a small number of ever-changing alliances contending for power, which culminated in the World Wars of the early 20th century.

In many periodizations of human history, the late modern period followed the early modern period. It began around 1800 and, depending on the author, either ended with the beginning of contemporary history in 1945, or includes the contemporary history period to the present day.

This article covers worldwide diplomacy and, more generally, the international relations of the great powers from 1814 to 1919. This era covers the period from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815), to the end of the First World War and the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920).