Related Research Articles

Junk science is spurious or fraudulent scientific data, research, or analysis. The concept is often invoked in political and legal contexts where facts and scientific results have a great amount of weight in making a determination. It usually conveys a pejorative connotation that the research has been untowardly driven by political, ideological, financial, or otherwise unscientific motives.

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims; reliance on confirmation bias rather than rigorous attempts at refutation; lack of openness to evaluation by other experts; absence of systematic practices when developing hypotheses; and continued adherence long after the pseudoscientific hypotheses have been experimentally discredited. It is not the same as junk science.

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced under the authority of a government, political party or other entity or individual. A dissenting person may be referred to as a dissenter.

HIV/AIDS denialism is the belief, despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) does not cause acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Some of its proponents reject the existence of HIV, while others accept that HIV exists but argue that it is a harmless passenger virus and not the cause of AIDS. Insofar as they acknowledge AIDS as a real disease, they attribute it to some combination of sexual behavior, recreational drugs, malnutrition, poor sanitation, haemophilia, or the effects of the medications used to treat HIV infection (antiretrovirals).

The scientific community is a diverse network of interacting scientists. It includes many "sub-communities" working on particular scientific fields, and within particular institutions; interdisciplinary and cross-institutional activities are also significant. Objectivity is expected to be achieved by the scientific method. Peer review, through discussion and debate within journals and conferences, assists in this objectivity by maintaining the quality of research methodology and interpretation of results.

The politicization of science for political gain occurs when government, business, or advocacy groups use legal or economic pressure to influence the findings of scientific research or the way it is disseminated, reported or interpreted. The politicization of science may also negatively affect academic and scientific freedom, and as a result it is considered taboo to mix politics with science. Historically, groups have conducted various campaigns to promote their interests in defiance of scientific consensus, and in an effort to manipulate public policy.

Science studies is an interdisciplinary research area that seeks to situate scientific expertise in broad social, historical, and philosophical contexts. It uses various methods to analyze the production, representation and reception of scientific knowledge and its epistemic and semiotic role.

Scientific consensus is the generally held judgment, position, and opinion of the majority or the supermajority of scientists in a particular field of study at any particular time.

Fringe science refers to ideas whose attributes include being highly speculative or relying on premises already refuted. Fringe science theories are often advanced by people who have no traditional academic science background, or by researchers outside the mainstream discipline. The general public has difficulty distinguishing between science and its imitators, and in some cases, a "yearning to believe or a generalized suspicion of experts is a very potent incentive to accepting pseudoscientific claims".

In philosophy of science and epistemology, the demarcation problem is the question of how to distinguish between science and non-science. It also examines the boundaries between science, pseudoscience and other products of human activity, like art and literature and beliefs. The debate continues after more than two millennia of dialogue among philosophers of science and scientists in various fields. The debate has consequences for what can be termed "scientific" in topics such as education and public policy.

Recurring cultural, political, and theological rejection of evolution by religious groups exists regarding the origins of the Earth, of humanity, and of other life. In accordance with creationism, species were once widely believed to be fixed products of divine creation, but since the mid-19th century, evolution by natural selection has been established by the scientific community as an empirical scientific fact.

Brian Martin is a social scientist in the School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities, at the University of Wollongong (UOW) in NSW, Australia. He was appointed a professor at the university in 2007, and in 2017 was appointed emeritus professor. His work is in the fields of peace research, scientific controversies, science and technology studies, sociology, political science, media studies, law, journalism, freedom of speech, education and corrupted institutions, as well as research on whistleblowing and dissent in the context of science. Martin was president of Whistleblowers Australia from 1996 to 1999 and remains their International Director. He has been criticized by medical professionals and public health advocates for promoting the disproven oral polio vaccine AIDS hypothesis and supporting vaccine hesitancy in the context of his work.

Antiscience is a set of attitudes and a form of anti-intellectualism that involves a rejection of science and the scientific method. People holding antiscientific views do not accept science as an objective method that can generate universal knowledge. Antiscience commonly manifests through rejection of scientific ideas such as climate change and evolution. It also includes pseudoscience, methods that claim to be scientific but reject the scientific method. Antiscience leads to belief in false conspiracy theories and alternative medicine. Lack of trust in science has been linked to the promotion of political extremism and distrust in medical treatments.

In the psychology of human behavior, denialism is a person's choice to deny reality as a way to avoid believing in a psychologically uncomfortable truth. Denialism is an essentially irrational action that withholds the validation of a historical experience or event when a person refuses to accept an empirically verifiable reality.

Climate change denial is a form of science denial characterized by rejecting, refusing to acknowledge, disputing, or fighting the scientific consensus on climate change. Those promoting denial commonly use rhetorical tactics to give the appearance of a scientific controversy where there is none. Climate change denial includes unreasonable doubts about the extent to which climate change is caused by humans, its effects on nature and human society, and the potential of adaptation to global warming by human actions. To a lesser extent, climate change denial can also be implicit when people accept the science but fail to reconcile it with their belief or action. Several studies have analyzed these positions as forms of denialism, pseudoscience, or propaganda.

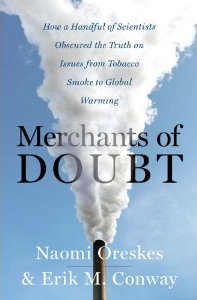

Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming is a 2010 non-fiction book by American historians of science Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway. It identifies parallels between the global warming controversy and earlier controversies over tobacco smoking, acid rain, DDT, and the hole in the ozone layer. Oreskes and Conway write that in each case "keeping the controversy alive" by spreading doubt and confusion after a scientific consensus had been reached was the basic strategy of those opposing action. In particular, they show that Fred Seitz, Fred Singer, and a few other contrarian scientists joined forces with conservative think tanks and private corporations to challenge the scientific consensus on many contemporary issues.

A manufactured controversy is a contrived disagreement, typically motivated by profit or ideology, designed to create public confusion concerning an issue about which there is no substantial academic dispute. This concept has also been referred to as manufactured uncertainty.

Miriam Solomon is Professor of Philosophy and Chair of the Philosophy Department as well as Affiliated Professor of Women's Studies at Temple University. Solomon's work focuses on the philosophy of science, social epistemology, medical epistemology, medical ethics, and gender and science. Besides her academic appointments, she has published two books and a large number of peer reviewed journal articles, and she has served on the editorial boards of a number of major journals.

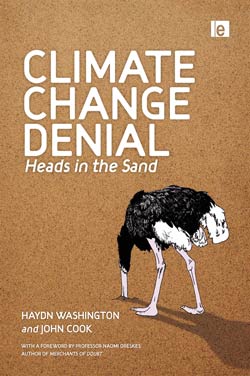

Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand is a 2011 non-fiction book about climate-change denial, coauthored by Haydn Washington and John Cook, with a foreword by Naomi Oreskes. Washington had a background in environmental science prior to authoring the work; Cook, educated in physics, founded (2007) the website Skeptical Science, which compiles peer-reviewed evidence of global warming. The book was first published in hardcover and paperback formats in 2011 by Earthscan, a division of Routledge.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 de Melo‐Martín, I. and Intemann, K. (2013) "Scientific dissent and public policy". EMBO Reports, 14 (3): 231–235. doi : 10.1038/embor.2013.8

- ↑ Diethelm, Pascal (2009). "Denialism: what is it and how should scientists respond?". The European Journal of Public Health. 19 (1): 2–4. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckn139. PMID 19158101.

- ↑ Wylie, Alison (2008). "A More Social Epistemology: Decision Vectors, Epistemic Fairness, and Consensus in Solomon's Social Empiricism". Perspectives on Science. 16 (3): 237–240. doi:10.1162/posc.2008.16.3.237. S2CID 57565947.

- 1 2 3 Schmaus, W. (2005). "Book Review: What's So Social about Social Knowledge?". Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 35 (1): 98–125. doi:10.1177/0048393104271927. ISSN 0048-3931. S2CID 143968901.

- ↑ John T. Blackmore, Ernst Mach; His Work, Life, and Influence, University of California Press, 1972, p. 206.

- ↑ Mary Jo Nye, Molecular Reality: A perspective on the Scientific Work of Jean Perrin, Macdonald, 1972, p. 151.

- ↑ "History of Ulcer Diagnosis and Treatment". CDC. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Delborne, J.A. (2016) "Suppression and Dissent in Science". In: Tracey Ann Bretag (Ed) Handbook of Academic Integrity, 64: 943–956. Springer. ISBN 9789812870971.

- 1 2 "Keeping Modern Myths And Conspiracy Theories At Bay", April 7, 2014, Asian Scientist Magazine

- ↑ Matthew J. Brauer, Daniel R. Brumbaugh, "Biology Remystified: The Scientific Claims of the New Creationists," in: Intelligent Design Creationism and Its Critics: Philosophical, Theological, and Scientific Perspectives, MIT Press, 2001, ISBN 0262661241, pp. 322, 323

- ↑ David Harker, Creating Scientific Controversies: Uncertainty and Bias in Science and Society, ISBN 1107069610, Cambridge University Press, 2015

- ↑ Daniel T. Willingham, When Can You Trust the Experts?: How to Tell Good Science from Bad in Education, Wiley, 2012, ISBN 1118233271, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Michael D. Gordin, The Pseudoscience Wars: Immanuel Velikovsky and the Birth of the Modern Fringe, University of Chicago Press, 2012, ISBN 0226304434, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Jean Paul Van Bendegem, "Argumentation and Pseudoscience The Case for an Ethics of Argumentation," In Massimo Pigliucci & Maarten Boudry (eds.), Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem, University of Chicago Press, 2013, ISBN 022605182X, p. 298.

- ↑ Aklin, M. and Urpelainen, J. (2014) "Perceptions of scientific dissent undermine public support for environmental policy". Environmental Science & Policy, 38: 173–177. doi : 10.1016/j.envsci.2013.10.006

- ↑ Sheila Jasanoff, "Cosmopolitan Knowledge: Climate Science and Global Civic Epistemology", in: The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society, 2011, ISBN 0199566607