In economics, Kondratiev waves are hypothesized cycle-like phenomena in the modern world economy. The phenomenon is closely connected with the technology life cycle.

In business theory, disruptive innovation is innovation that creates a new market and value network or enters at the bottom of an existing market and eventually displaces established market-leading firms, products, and alliances. The term, "disruptive innovation" was popularized by the American academic Clayton Christensen and his collaborators beginning in 1995, but the concept had been previously described in Richard N. Foster's book "Innovation: The Attacker's Advantage" and in the paper Strategic Responses to Technological Threats.

Business cycles are intervals of general expansion followed by recession in economic performance. The changes in economic activity that characterize business cycles have important implications for the welfare of the general population, government institutions, and private sector firms. There are numerous specific definitions of what constitutes a business cycle. The simplest and most naïve characterization comes from regarding recessions as 2 consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. More satisfactory classifications are provided by, first including more economic indicators and second by looking for more informative data patterns than the ad hoc 2 quarter definition.

Carlota Perez is a British-Venezuelan scholar specialized in technology and socio-economic development. She researches the concept of Techno-Economic Paradigm Shifts and the theory of great surges, a further development of Schumpeter's work on Kondratieff waves. In 2012 she was awarded the Silver Kondratieff Medal by the International N. D. Kondratieff Foundation and in 2021 she was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by Utrecht University.

Leapfrogging is a concept used in many domains of the economics and business fields, and was originally developed in the area of industrial organization and economic growth. The main idea behind the concept of leapfrogging is that small and incremental innovations lead a dominant firm to stay ahead. However, sometimes, radical innovations will permit new firms to leapfrog the ancient and dominant firm. The phenomenon can occur to firms but also to leadership of countries or cities, where a developing country can skip stages of the path taken by industrial nations, enabling them to catch up sooner, particularly in terms of economic growth.

Erich Jantsch was an American astrophysicist, engineer, educator, author, consultant and futurist, especially known for his work in the social systems design movement in Europe in the 1970s.

Giovanni Dosi is Professor of Economics and Director of the Institute of Economics at the Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna in Pisa. He is the Co-Director of the task forces “Industrial Policy” and “Intellectual Property” at the Initiative for Policy Dialogue at Columbia University. Dosi is Continental European Editor of Industrial and Corporate Change. Included in ISI Highly Cited Researchers.

Jeong-dong Lee is a Korean academic currently serving as the Special Advisor to the President on Economy and Science since his appointment by President Moon Jae-in in January 2019. He is a professor of Interdisciplinary Graduate Program on Technology Management, Economics and Policy (TEMEP) and the Department of Industrial Engineering at Seoul National University, Korea.

Technology dynamics is broad and relatively new scientific field that has been developed in the framework of the postwar science and technology studies field. It studies the process of technological change. Under the field of Technology Dynamics the process of technological change is explained by taking into account influences from "internal factors" as well as from "external factors". Internal factors relate technological change to unsolved technical problems and the established modes of solving technological problems and external factors relate it to various (changing) characteristics of the social environment, in which a particular technology is embedded.

Innovation economics is new, and growing field of economic theory and applied/experimental economics that emphasizes innovation and entrepreneurship. It comprises both the application of any type of innovations, especially technological, but not only, into economic use. In classical economics this is the application of customer new technology into economic use; but also it could refer to the field of innovation and experimental economics that refers the new economic science developments that may be considered innovative. In his 1942 book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, economist Joseph Schumpeter introduced the notion of an innovation economy. He argued that evolving institutions, entrepreneurs and technological changes were at the heart of economic growth. However, it is only in recent years that "innovation economy," grounded in Schumpeter's ideas, has become a mainstream concept".

The technological innovation system is a concept developed within the scientific field of innovation studies which serves to explain the nature and rate of technological change. A Technological Innovation System can be defined as ‘a dynamic network of agents interacting in a specific economic/industrial area under a particular institutional infrastructure and involved in the generation, diffusion, and utilization of technology’.

A technological revolution is a period in which one or more technologies is replaced by another novel technology in a short amount of time. It is a time of accelerated technological progress characterized by innovations whose rapid application and diffusion typically cause an abrupt change in society.

Tessaleno Campos Devezas is a Brazilian-born Portuguese physicist, systems theorist, and materials scientist. He is best known for his contributions to the long waves theory in socioeconomic development, technological evolution, energy systems as well as world system analysis.

A reverse salient refers to a component of a technological system that, due to its insufficient development, prevents the system in its entirety from achieving its development goals. The term was coined by Thomas P. Hughes, in his work Networks of power: Electrification in western society, 1880-1930.

Transition management is a governance approach that aims to facilitate and accelerate sustainability transitions through a participatory process of visioning, learning and experimenting. In its application, transition management seeks to bring together multiple viewpoints and multiple approaches in a 'transition arena'. Participants are invited to structure their shared problems with the current system and develop shared visions and goals which are then tested for practicality through the use of experimentation, learning and reflexivity. The model is often discussed in reference to sustainable development and the possible use of the model as a method for change.

Transition scenarios are descriptions of future states which combine a future image with an account of the changes that would need to occur to reach that future. These two elements are often created in a two-step process where the future image is created first (envisioning) followed by an exploration of the alternative pathways available to reach the future goal (backcasting). Both these processes can use participatory techniques where participants of varying backgrounds and interests are provided with an open and supportive group environment to discuss different contributing elements and actions.

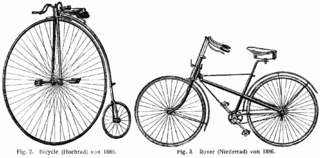

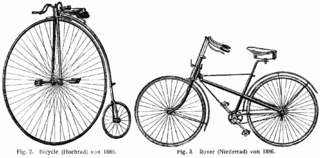

The sailing ship effect is a phenomenon by which the introduction of a new technology to a market accelerates the innovation of an incumbent technology. Despite the fact that the term was coined by W.H. Ward in 1967 the concept was made clear much earlier in a book by S.C. Gilfillan entitled “Inventing the ship” published in 1935. The name of the “effect” is due to the reference to advances made in sailing ships in the second half of the 1800s in response to the introduction of steamships. According to Ward, in the 50 years after the introduction of the steam ship, sailing ships made more improvements than they had in the previous 300 years. The term “Sailing Ship Effect” applies to situations in which an old technology is revitalized, experiencing a “last gasp” when faced with the risk of being replaced by a newer technology. Here is how Gilfillan put it: ”It is paradoxical, but on examination logical, that this noble flowering of the sailing ship, this apotheosis during her decline and just before extermination, was partly vouchsafed by her supplanter, the steamer.”.

Johannes Willem "Johan" Schot is a Dutch historian working in the field of science and technology policy. A historian of technology and an expert in sustainability transitions, Johan Schot is Professor of Global Comparative History at the Centre for Global Challenges, Utrecht University. He is the Academic Director of the Transformative Innovation Policy Consortium (TIPC) and former Director of the Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU) at the University of Sussex. He was elected to the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) in 2009. He is the Principal Investigator of the Deep Transitions Lab.

Eco-restructuring is the implication for an ecologically sustainable economy. The principle of ecological modernization establishes the core literature of the functions that eco-restructuring has within a global regime. Eco-restructuring has an emphasis on the technological progressions within an ecological system. Government officials implement environmental policies to establish the industrial- ecological progressions that enable the motion of economic modernization. When establishing economic growth, policy makers focus on the progression towards a sustainable environment by establishing a framework of ecological engineering. Government funding is necessary when investing in efficient technologies to stimulate technological development.

Green industrial policy (GIP) is strategic government policy that attempts to accelerate the development and growth of green industries to transition towards a low-carbon economy. Green industrial policy is necessary because green industries such as renewable energy and low-carbon public transportation infrastructure face high costs and many risks in terms of the market economy. Therefore, they need support from the public sector in the form of industrial policy until they become commercially viable. Natural scientists warn that immediate action must occur to lower greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change. Social scientists argue that the mitigation of climate change requires state intervention and governance reform. Thus, governments use GIP to address the economic, political, and environmental issues of climate change. GIP is conducive to sustainable economic, institutional, and technological transformation. It goes beyond the free market economic structure to address market failures and commitment problems that hinder sustainable investment. Effective GIP builds political support for carbon regulation, which is necessary to transition towards a low-carbon economy. Several governments use different types of GIP that lead to various outcomes. The Green Industry plays a pivotal role in creating a sustainable and environmentally responsible future; By prioritizing resource efficiency, renewable energy, and eco-friendly practices, this industry significantly benefits society and the planet at large.