History

Henry VI and Frederick II

William III of Sicily was deposed in 1194 and was succeeded by his grandaunt Constance of Altaville, who nine years earlier had married Henry VI, son of Frederick Barbarossa. Henry himself died in 1197 - his widow ruled Sicily alone for a year and a few months. Before her death she had their four-year-old son Frederick II crowned, creating the new Hohenstaufen dynasty on Sicily. She then ruled as regent on his behalf until her death in 1198, upon which pope Innocent III took over as Frederick's guardian, entrusting him to a regency council and recognising him as heir to the throne of Sicily.

From 1201 to 1206 Markward von Annweiler ruled as regent, followed by William of Capparone, with Frederick only reaching his majority at the age of fourteen in 1208. Palermo and its court became the centre of the Empire, comprising Apulia and western Italy, and there was born the Sicilian School, the first distinctly Italian poetic school. Frederick himself became known as the stupor mundi (marvel of the world), argued by Santi Correnti to have been "the forerunner of the Renaissance prince". He wrote the Constitutions of Melfi in 1231 and from 1220 to 1239 expelled and deported the remaining Muslims on Sicily, ending with the final deportation of all Siculo Muslims to the Lucera in Foggia.

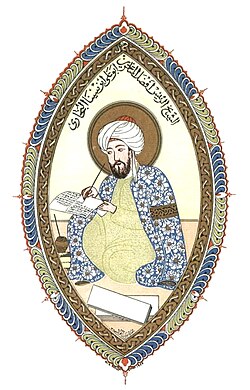

Frederick II was one of the greatest, most energetic, imaginative and capable rulers of the entire Middle Ages. He was also perhaps the most powerful monarch and ruled a vast area, beginning with Sicily and stretching through Italy all the way north to Germany. In the Kingdom of Sicily and much of Italy, Frederick built upon the work of his Norman predecessors and forged an early absolutist state bound together by an efficient secular bureaucracy. He enjoys a reputation as a brilliant Renaissance man avant la lettre and a visionary statesman, scientist, scholar, architect, poet and composer. [1] [2] [3] Frederick also reportedly spoke six languages: Latin, Sicilian, Middle High German, Old French, Greek, and Arabic. [4] [5] As an avid patron of science and the arts, he played a major role in promoting literature through the Sicilian School of poetry. His Sicilian royal court in Palermo and Foggia, beginning around 1220, saw the first use of a literary form of an Italo-Romance language, Sicilian. The poetry that emanated from the school had a significant influence on literature and on what was to become the modern Italian language. [6] His most profound legal legacy remains the Constitutions of Melfi or Constitutiones Regni Siciliarum (English: Constitutions of the Kingdom of the Sicilies), promulgated in 1231 in the Kingdom of Sicily. The sophistication of the Constitutions, also known as the Liber Augustalis, sets Frederick apart as perhaps the supreme lawgiver of the Middle Ages. [7] Almost every aspect in Frederick’s tightly-governed kingdom was regulated, from a rigorously centralized judiciary and bureaucracy, to commerce, coinage, financial policy, legal equality for all citizens, protections for women, and even provisions for the environment and public health. State monopolies were imposed on silk, iron, and grain while tariffs and import duties on trade within the kingdom were abolished. A new gold coin called an augustalis was introduced and became widely circulated in Italy, admired even today for its splendid proto-Renaissance style and fine quality. [8] Per the Constitutions, Frederick was lex animata and ruled as an absolute monarch. The Constitutions have been regarded as perhaps the “birth certificate” of the modern continental European state. [9]

Frederick II was often conflict with the papacy and several northern Italian cities for a large part of his rule. From the latter period of his reign, Frederick enacted far-reaching reforms to establish the Sicilian kingdom and Imperial Italy as unified state bound by a centralized administration. However, despite his might efforts, his newly unified Italian state proved ephemeral. Nevertheless, though the situation was ever fluid and Frederick suffered several setbacks in his final years, by the end of his life he was again in the ascendent against his enemies and left his sons a strong position, naming his oldest legitimate son Conrad IV his heir in Germany, Italy, and Sicily, whilst Manfred was named regent of Sicily and Italy in Conrad’s absence.

Manfred of Sicily

In October 1251 Conrad left for the Italian mainland, where he met the Imperial deputies, and in January the following year he landed at Siponto, from which he and Manfred pacified the Kingdom after small papal-supported rebellions had broken out. In 1253 they retook the rebelling counties of Caserta and Acerra and conquered Capua, finally taking Naples that October. Conrad died of malaria on 21 May 1254 (there is no evidence for the rumour that Manfred poisoned his half-brother), making the pope the guardian of his son Conradin.

The pope, however, remained unfavourable to the Swabian dynasty and instead promised the Kingdom of Sicily to Edmund the Hunchback so long as he could occupy it with an army. However, thanks to the diplomatic skills he had inherited from his father, Manfred reached an agreement with the pope, allowing the papal occupation of the army but reserving the rights of Conradin and his family. Despite this, Manfred still did not feel himself safe from the pope and so raised to huge army to oppose the papal forces, meeting them near Foggia. Over the course of 1257 Manfred defeated the papal army as well as putting down internal rebellions, but his army was dispersed in 1258, probably on Manfred's own orders. [10]

On Conradin's rumoured death, the Sicilian prelates and barons invited Manfred himself to take the throne and he was crowned at Palermo Cathedral on 10 August. This was not recognised by pope Alexander IV, who regarded Manfred as a usurper. Heading the Ghibelline faction which existed throughout mainland Italy, Manfred's power grew, particularly by marrying his daughter Constance to Peter III of Aragon in 1262. Manfred was ultimately excommunicated and Pope Urban IV offered the Kingdom of Sicily to Charles I of Anjou, brother to Louis IX of France. Charles marched against Manfred, decisively defeating him at the Battle of Benevento on 26 February 1266. Two years later Conradin himself tried to retake the Kingdom but was defeated at the Battle of Tagliacozzo and beheaded.

Postscript

Manfred's daughter Constance claimed the Kingdom of Sicily in 1281 and after the Sicilian Vespers became queen of Sicily from 1282 to 1285, uniting it to her husband Peter's domains. Peter was crowned King of Aragon in 1282 and thus remained in Spain from 1283 until his death in 1285, upon which the Kingdom of Sicily passed to his second son James, assisted in his rule of Sicily by his mother. He remained on the island until the death of his elder brother Alfonso III of Aragon in 1291 and his accession to the throne of Aragon, returning to Spain and leaving Peter's third son Frederick behind as lieutenant of the Kingdom of Sicily. James made peace with France and intended to cede the island of Sicily to Charles's son Charles II, but its nobility instead crowned Frederick king, ultimately confirmed by the 1302 Peace of Caltabellotta.