German is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Western and Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is also an official language of Luxembourg and Belgium, as well as a recognized national language in Namibia. Outside Germany, it is also spoken by German communities in France (Alsace), Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary (Sopron).

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlements and chronologically coincides with the Viking Age, the Christianization of Scandinavia and the consolidation of Scandinavian kingdoms from about the 8th to the 15th centuries.

The Germanic umlaut is a type of linguistic umlaut in which a back vowel changes to the associated front vowel (fronting) or a front vowel becomes closer to (raising) when the following syllable contains, , or.

Swabian is one of the dialect groups of Upper German, sometimes one of the dialect groups of Alemannic German, that belong to the High German dialect continuum. It is mainly spoken in Swabia, which is located in central and southeastern Baden-Württemberg and the southwest of Bavaria. Furthermore, Swabian German dialects are spoken by Caucasus Germans in Transcaucasia. The dialects of the Danube Swabian population of Hungary, the former Yugoslavia and Romania are only nominally Swabian and can be traced back not only to Swabian but also to Franconian, Bavarian and Hessian dialects, with locally varying degrees of influence of the initial dialects.

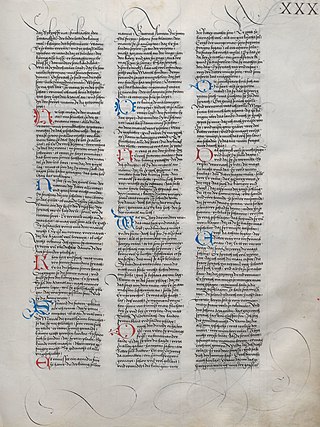

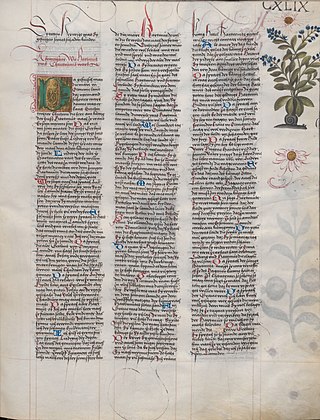

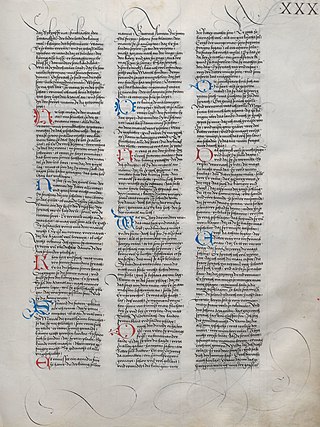

Middle Dutch is a collective name for a number of closely related West Germanic dialects whose ancestor was Old Dutch. It was spoken and written between 1150 and 1500. Until the advent of Modern Dutch after 1500 or c. 1550, there was no overarching standard language, but all dialects were mutually intelligible. During that period, a rich Medieval Dutch literature developed, which had not yet existed during Old Dutch. The various literary works of the time are often very readable for speakers of Modern Dutch since Dutch is a rather conservative language.

Early New High German (ENHG) is a term for the period in the history of the German language generally defined, following Wilhelm Scherer, as the period 1350 to 1650.

Alemannic, or rarely Alemannish, is a group of High German dialects. The name derives from the ancient Germanic tribal confederation known as the Alemanni.

Old High German is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally identified as the period from around 500/750 to 1050. Rather than representing a single supra-regional form of German, Old High German encompasses the numerous West Germanic dialects that had undergone the set of consonantal changes called the Second Sound Shift.

German orthography is the orthography used in writing the German language, which is largely phonemic. However, it shows many instances of spellings that are historic or analogous to other spellings rather than phonemic. The pronunciation of almost every word can be derived from its spelling once the spelling rules are known, but the opposite is not generally the case.

In historical linguistics, the High German consonant shift or second Germanic consonant shift is a phonological development that took place in the southern parts of the West Germanic dialect continuum in several phases. It probably began between the third and fifth centuries and was almost complete before the earliest written records in High German were produced in the eighth century. From Proto-Germanic, the resulting language, Old High German, can be neatly contrasted with the other continental West Germanic languages, which for the most part did not experience the shift, and with Old English, which remained completely unaffected.

Low Alemannic German is a branch of Alemannic German, which is part of Upper German. Its varieties are only partly intelligible to non-Alemannic speakers.

In historical linguistics, vowel breaking, vowel fracture, or diphthongization is the sound change of a monophthong into a diphthong or triphthong.

The Old Polish language was a period in the history of the Polish language between the 10th and the 16th centuries. It was followed by the Middle Polish language.

Erzgebirgisch is a (East) Central German dialect, spoken mainly in the central Ore Mountains in Saxony. It has received relatively little academic attention. Due to the high mobility of the population and the resulting contact with Upper Saxon, the high emigration rate and its low mutual intelligibility with other dialects, the number of speakers is decreasing.

Old Norse has three categories of verbs and two categories of nouns. Conjugation and declension are carried out by a mix of inflection and two nonconcatenative morphological processes: umlaut, a backness-based alteration to the root vowel; and ablaut, a replacement of the root vowel, in verbs.

Middle High German literature refers to literature written in German between the middle of the 11th century and the middle of the 14th. In the second half of the 12th century, there was a sudden intensification of activity, leading to a 60-year "golden age" of medieval German literature referred to as the mittelhochdeutsche Blütezeit. This was the period of the blossoming of Minnesang, MHG lyric poetry, initially influenced by the French and Provençal tradition of courtly love song. The same sixty years saw the composition of the most important courtly romances. again drawing on French models such as Chrétien de Troyes, many of them relating Arthurian material. The third literary movement of these years was a new revamping of the heroic tradition, in which the ancient Germanic oral tradition can still be discerned, but tamed and Christianized and adapted for the court.

Erec is a Middle High German poem written in rhyming couplets by Hartmann von Aue. It is thought to be the earliest of Hartmann's narrative works and dates from around 1185. An adaptation of Chrétien de Troyes' Erec et Enide, it is the first Arthurian Romance in German.

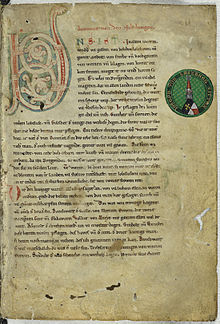

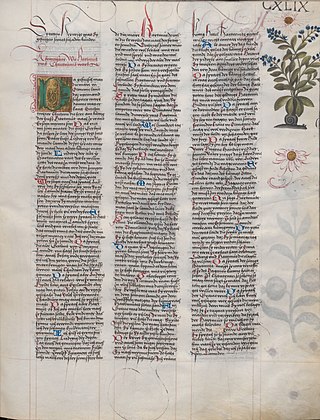

The Ambraser Heldenbuch is a 16th-century manuscript written in Early New High German, now held in the Austrian National Library. It contains a collection of 25 Middle High German courtly and heroic narratives along with some shorter works, all dating from the 12th and 13th centuries. For many of the texts it is the sole surviving source, which makes the manuscript highly significant for the history of German literature. The manuscript also attests to an enduring taste for the poetry of the MHG classical period among the upper classes.

In the Middle High German (MHG) period (1050–1350) the courtly romance, written in rhyming couplets, was the dominant narrative genre in the literature of the noble courts, and the romances of Hartmann von Aue, Gottfried von Strassburg and Wolfram von Eschenbach, written c. 1185 – c. 1210, are recognized as classics.

The Central Hessian dialect is a German dialect subgroup of the Hessian branch of Central German. It has only partly undergone the High German (HG) consonant shift but has had a different vowel development than most other German dialects.